Below Deck at Back Channel Radio

What it takes to document a subculture from the inside: a community archivist tells the story of the only year-round habitable boathouse community left on the Mississippi River

This article contains spoilers about the Back Channel Radio Podcast.

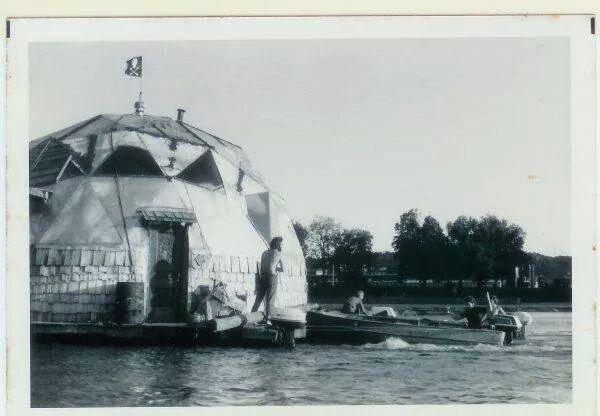

On the morning I received confirmation about this essay, it was raining inside. “Great!” I emailed back, then ran into my studio to do further damage control, moving electronics, paper, and books out of harm’s way, covering records and paintings with scraps of plastic sheeting. I myself was wearing a raincoat. I live in a geodesic dome-shaped boathouse (or more accurately, a floating home) that was inexpertly constructed 50 years ago and has since sunk at least twice. Which is to say, the many seams on the roof are prone to leaking, although way less than they used to be. It floats in the only year-round habitable boathouse community left on the Mississippi River, located on Latsch Island near Winona, MN.

My partner and I work on it perpetually, and have for years now, but this winter has been different. The leaks aren’t coming from outside; rather, they’re the result of condensation that’s occurring from temperature fluctuations. This is but one example of challenges that come up on the daily—living on water, away from a road, and unhooked from the grid. Other contextual details can be gleaned from listening to the six-episode oral docuseries Back Channel Radio.

Despite this place being special to the DIY boating subculture and important to a wide swath of Minnesotans in general, no one I asked was ever able to provide all the details, the complete picture of when the boathouses showed up and why they were allowed to stay. It was always put forth in bits and pieces of contradictory information and hearsay. A Wikipedia page for the boathouses popped up sometime within the last three years, containing lots of dubious information cited from sources like newspaper articles of interviews from the 80s that were almost all opinion and secondhand accounts.

YouTubers and travel show camera crews appear every year with their own agendas, which span the spectrum of romanticizing the community, likening the boathousers to Huck Finn, and amassing as many views as possible through sensationalizing the lifestyle and omitting any crucial details, if they’re asked about at all. Tales of rugged rivermen, alone in their boats with maybe a dog and a gun: that legend is intact.

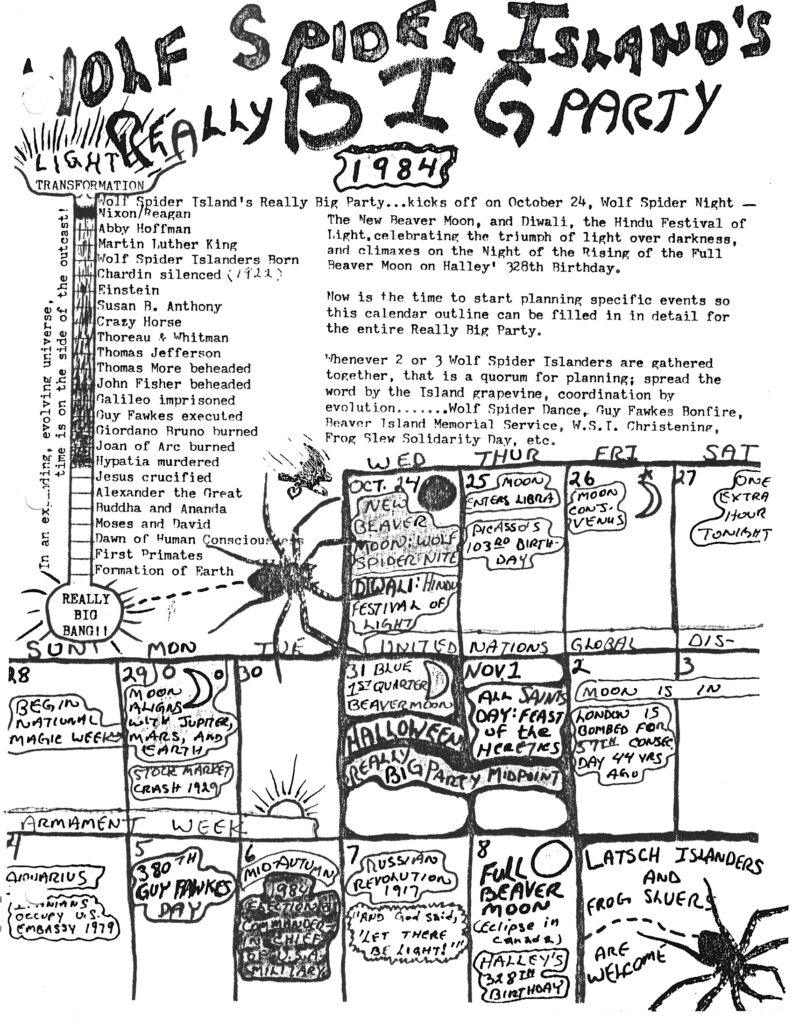

Here on the island, I came to know characters that were just as, if not more, audacious. Queer stories, stories of radical resistance, stories of older women living alone in this insanely wild place. I was afraid they would slowly disintegrate like the shrinking shoreline, be absorbed by following generations, and eventually forgotten. I wanted to record the stories of innovation that come from unconventional living executed without much means, the legacy of an anti-authoritarian subculture.

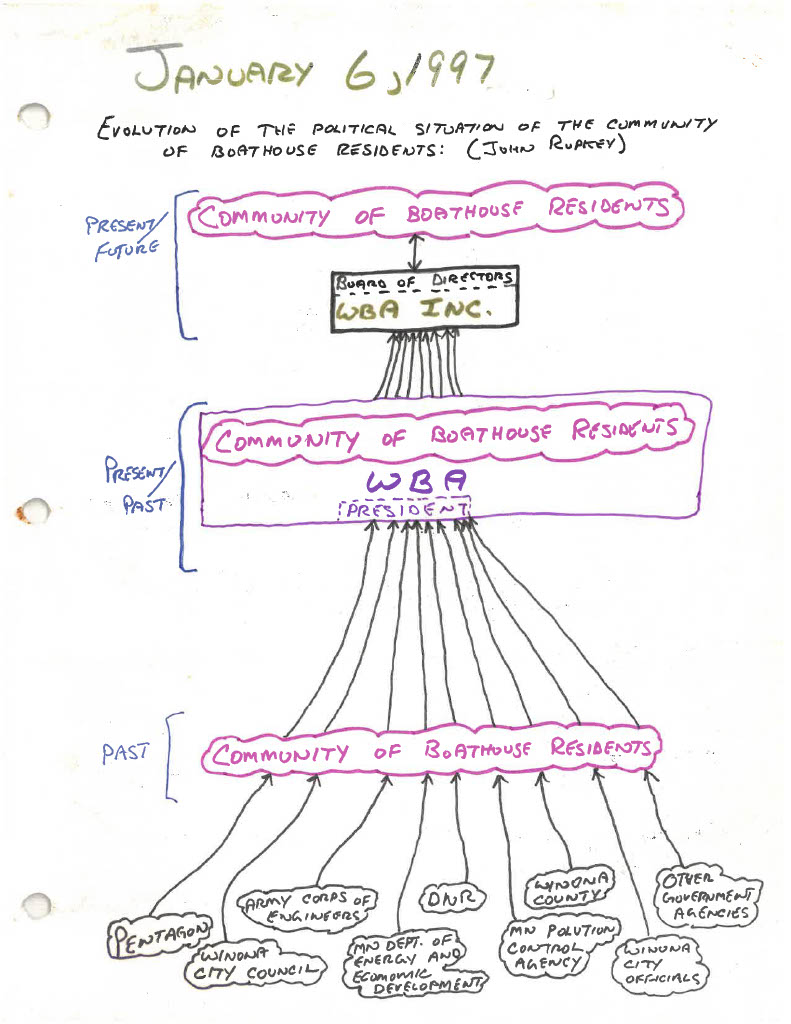

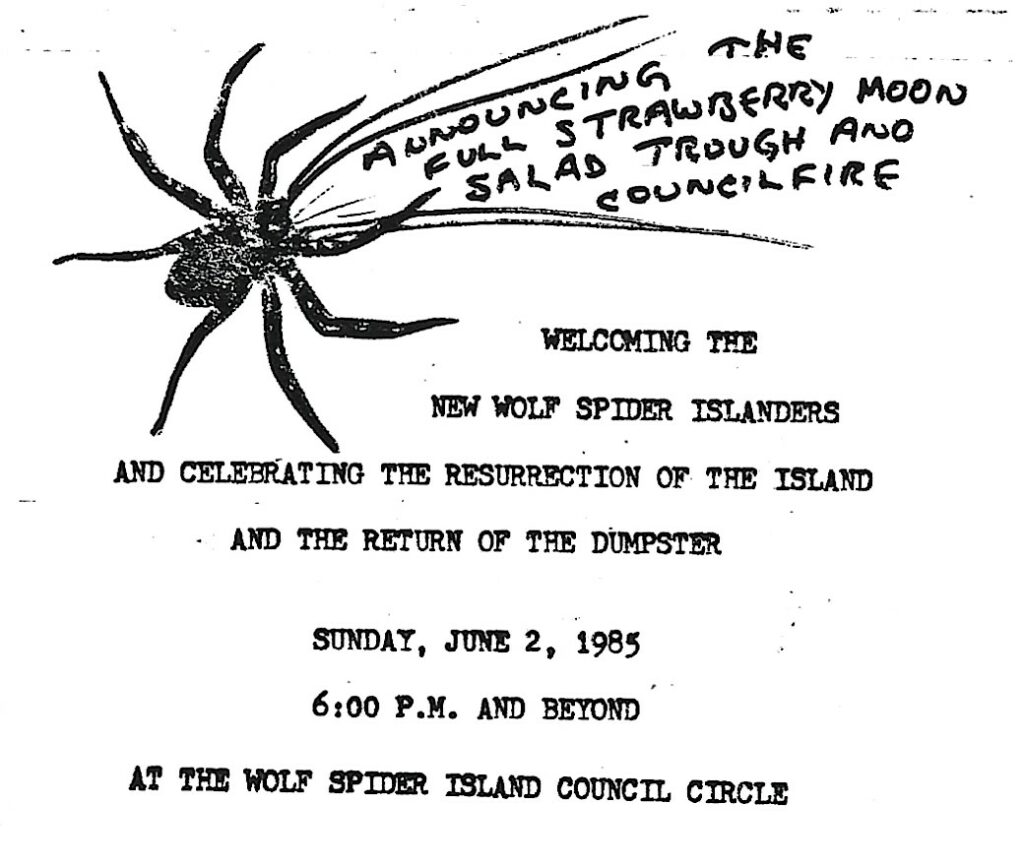

My neighbor and friend John Rupkey was the scribe of this community, and had been for the 43 years he lived here. His archives were and are treasure, literal treasure. Here was someone who thankfully had the foresight to save all of the hard copy documentation of the history of the islanders, of the legal battles they had to wage in order for their community to become sanctioned, and the subculture that was blossoming alongside their floating dwellings. It was a detailed snapshot of a counterculture from a specific time, in a specific place. Tomes of carefully organized materials, most of it chronologically bound, inevitably musty and wilted in the damp environ (the details of their discovery are described towards the end of the first podcast episode.)

For me, the most compelling cross-section of the story was the mandorla of where John’s personal background and the history of the island overlapped, the rare nexus of those two parallel narratives. They were both accounts of a search for freedom. I knew John peripherally, I knew a bit about his story. I knew he had been a member of a religious order, which he left when he came out to live as a gay man. I knew that his partner had lived on the island, and that he had died of AIDS-related causes years ago.

I set out to digitize John’s many hundreds of documents, and sent an unsolicited email to the county historical society to gauge what their level of interest and support might be in adding the files to their annals. They were pleasantly enthusiastic about the possibilities; up until now, they had only one thin manila envelope containing a few xeroxed newspaper articles, depicting the barest outline of this place that’s become so iconic in this region. But it required massive effort on my part. Next came the chapter of spending many stuffy, masked hours scanning dogeared documents in the history center basement, amidst stacks of microfiche, beneath judging eyes of tintype portraits and shelves of haunted objects. The path was arduous but unclear.

Towards the beginning of the archiving process, I often found myself saying something along the lines of: “I’m not the right person for this job.” The story needed to be secured, but I didn’t necessarily need (or want) to be the one to do it. In hindsight, I was able to record the story properly because I’m a member of the community. These were relationships that I cared about and felt protective of, that were built upon a foundation of trust. Part of what also made it possible for me to tell it was that I wasn’t from here. I grew up on the East Coast, in Philadelphia, where no community like this would be permitted to exist in any semblance of perpetuity. It was fascinating. It also presented a specialized challenge—I felt a heavy yoke of responsibility to represent the community in an accurate way, rooted in respect for the varied groupings of boat punks, river rats, recluses, naturalists, hippies, weekenders, and townsfolk, and to try to maintain a narrator’s neutral tone. Having lived most of my life in subcultures that were on the fringes of mainstream society, I understood the carefulness demanded by the situation, the unspoken precedent of “don’t blow up the spot.”

When I approached John about the possibility of recording an interview with him, I wasn’t sure what his reaction would be. A lot of the first wave boathousers who are still around have a healthy skepticism about committing to being interviewed (and who can blame them, given some of the previous attempts?) He agreed, and we embarked together on a journey of documentation that took place over the course of about two dozen recorded conversations. At that point, I wasn’t thinking much about if or how they’d be publicly broadcast. Those early files have lots of eating noises, rustling, wind blowing against the recorder. Naiveté can be a boon when it comes to entering uncharted territory, but made for more work during the editing process.

I knew the interviews were something valuable that should be shared, but the details weren’t clear on the best way to do it. My friend Suzanne Hogan works in public radio down in Kansas City, and I gave her a call to see if she’d be interested in taking it on with me. Suzanne and I know each other from us both playing in punk bands, she being the bass player in the rock ‘n’ roll trio Nature Boys, and over the years our paths would sometimes cross on tour. After a few conversations brainstorming different possibilities, a plan was hatched to turn the material into a podcast. We used Google Drive and Zoom to help facilitate our mostly long-distance collaboration.

Partnering with Suzanne pushed the project towards clarity, distilling expansive narratives down into episodes that were more easily absorbed by the listener. What made it doubly fortuitous was that she had visited the island before, and had a reference for the place and for aspects of the culture. Suzanne convinced me that it was important to include myself in the episodes, an idea I was initially resistant to. We teamed up with Grace Ambrose to help design the website.

I submitted grant proposals with a prototype trailer I made on my home recording setup. The project’s timeline and ultimate fruition was hastened by the pandemic, especially during that first year of COVID, when the perpetual anxiety that we’re still living under was fresh and we hadn’t yet adjusted to its constancy. The delineated parameters of archiving, research, and drafting podcast scripts gave me something defined to dig into that wasn’t surreal or scary in the same way the rest of the world was. It took the span of about two years to develop the raw material into podcast form. I utilized Temis, the magical timesaving automatic transcription service that can be found online. Early on in the scriptwriting process, I had to switch gears from creative to investigative in order to fact check all of the information that would be presented publicly, which added several more weeks of work.

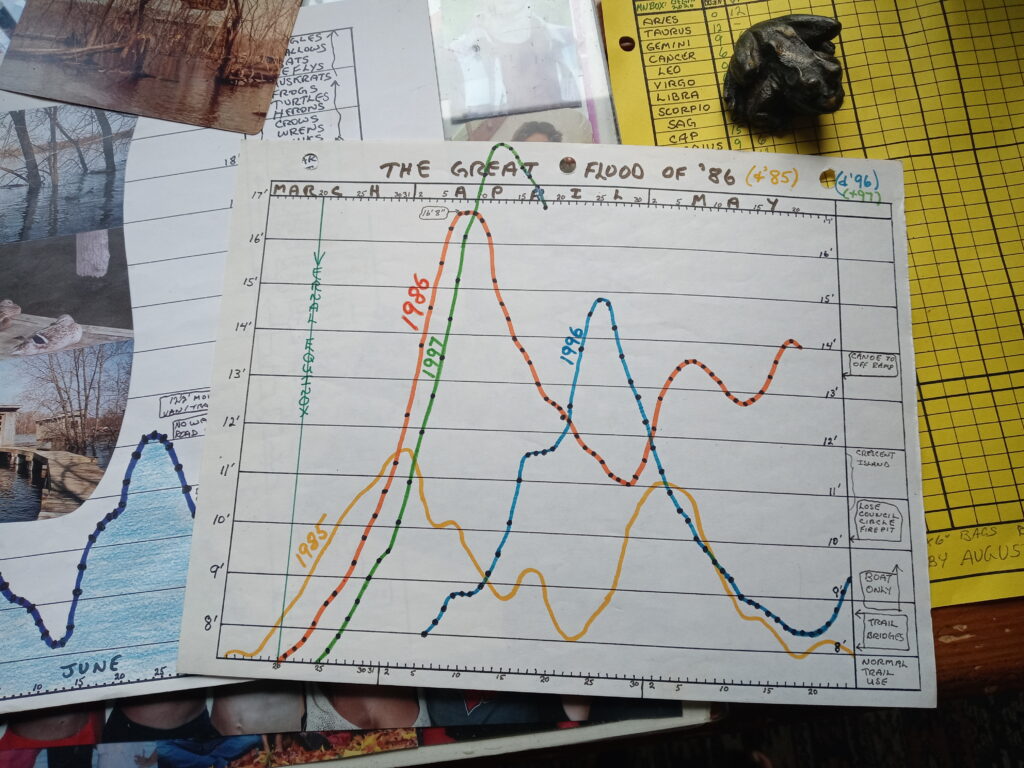

To be shaped by a place is to be limited by it, and occasionally hindered. I endured in real time the same hardships I was writing about: floods, freezing temperatures, sinking boats. Technical difficulties, almost always present in most equipment-reliant endeavors, run rampant in a boathouse: for example, the grounding issues I was having recording myself while over water, exacerbated by the battery bank connected to the solar panels. An extraterrestrial-sounding, buzzing drone would saturate everything, and wasn’t audible until the recording was played back. This led to lots of experimenting, recording myself sitting under blankets in different boats to see if it could affect the outcome. On cloudy days, power is inconsistent, and the backup generator is too loud to permit recording. That coupled with unreliable internet access actually led to me renting a studio on land for part of the time it took to edit and arrange all of the files.

Once I started to get into the factual weeds of history, it started to leave some blank spots, questions that needed to be asked and answered. I started researching people who used to live on the island, but don’t anymore—some now deceased, like the Judge Dennis Challeen who was once commonly known as the father of community-service sentencing, what we now know as restorative justice. There were other important stories that had to be omitted for various reasons, including privacy. There were the losses of my father and brother-in-law that do not appear in the narration, despite how they weirdly paralleled the deaths of John and our friend Tyra (Episodes 5 and 6) in the same time frame. Although I was essentially a character in the podcast, there was no succinct or convenient way to weave my family’s grief into the greater story arcs.

I played chess with John Rupkey the day he died. The staff at the medical facility where he passed away wouldn’t reveal the details of his death to me, even though I was on his HIPAA list. I didn’t push back, although I probably could have. I was preoccupied with securing the details about his life, and besides, I had been with him just a few hours before. On John’s last day, he clearly had one foot in another dimension. He was pointing to things we couldn’t see, turning to communicate with us what he was looking at, in a new and cryptic way. Excited but peaceful, like how babies sometimes are. He pointed with his finger crooked and asked us one by one, “Are you shedding goodness or badness?” until he got to my dog Willie, who I had placed near his lap. “Oh, you are always shedding goodness!” he said, as he gathered Willie’s face in both hands. We all knew what he meant. Towards the end of our visit, John raised his head and, so quietly, asked, “How’s that river? Is it still wild? Is it wild?” Then smiled and sank back down after we assured him that yes, it was indeed still wild.