“Space, Time, and Illusion”: Sage Cowles and Molly Davies

Camille LeFevre writes about the rare and beautiful performance of "Space, Time, and Illusion" at the Walker Art Center.

In the 1970s, Minneapolis dancer Sage Cowles teamed up with St. Paul filmmaker Molly Davies to produce a series of experimental works in which the filmed moving image and the live moving performer (always the same person, Cowles) were juxtaposed in space and time.

One Wednesday evening in the Walker Art Center’s McGuire Theater, the two now-older women introduced and showed excerpts from these explorations, grouped under the title “Space, Time and Illusion.” Cowles also recreated her live role.

How did audiences in the 70s respond to these “film performance pieces,” as Davies calls them? One might guess in the heyday of stripped-away style and anti-artifice, when presentation of the everyday in movement and content was radical, these works were rich fodder in the development of new forms. In the over-mediated, hyper-stimulating, pop-culture milieu of 2005, however, these spare and eloquent, visually meditative and aurally quiet works fulfill an essential role, by providing valuable insights into the true characteristics of compelling performance.

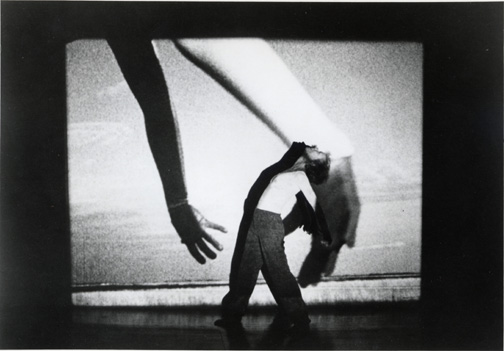

In other words, these excerpts are emotionally moving (but wholly unsentimental); dramatic (but utterly devoid of histrionics); simple (so their complexities can be revealed). In “The Run” section of “Grasslands and Sage,” for instance, Davies tells us she instructed Cowles to run toward her and the camera from a mile away, that she used a long lens to distort our sense of distance. We know exactly what’s going to happen.

Yet, as Cowles jogs closer (at times she seems to be running in place), the sound of her breathing gradually overtakes the early morning birdsong. Her body finally looms so large in the camera that after she passes by, the audience shuddered with a collective, kinesthetic relief. Now that’s drama. Through it all, the current Cowles sits quietly, eyes closed, on stage.

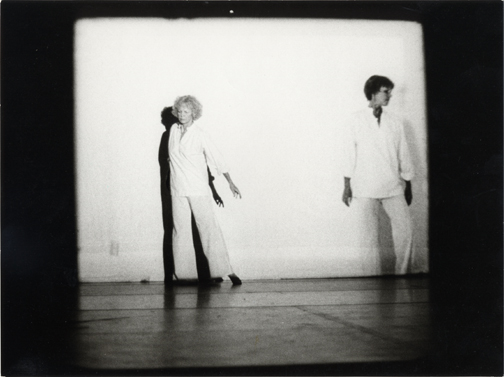

In the “Strings” section of “Grasslands and Sage,” Davies used two cameras to extend the horizontal line of the plains landscape. On film, Cowles hops from one frame to the other as she unrolls spools of string, while live on stage she hops a bit more gingerly between the strings she’s unspooled. In “Sage Time & Again,” the filmed brown-haired Cowles walks, extends her arms and pushes her hands against a section of wall framed by the camera lens, while the live white-haired Cowles shadows her younger self with similar movements. Eventually, the film is also projected within the film, creating three Cowleses of different times and sizes. One wants to ask her, “What’s it like to dance with your self?” “What goes through your mind?” “Is the tenderness I sense real or imagined?”

“Third Thought” is a pristine, intimate portrait of Cowles in triptych. On the left screen, filmed Cowles is projected in freeze-frame movements. On the right screen, she’s flying within a jet-black background. On the middle screen, she’s seen behind the glass wall of her cabin, slowly doing chores. When the live Cowles (all are dressed in white) pulls back the sliding glass door just as the filmed Cowles pulls open the screen, the audience gasps at the sudden delightful breach in perceptions of “reality” and “illusion.”

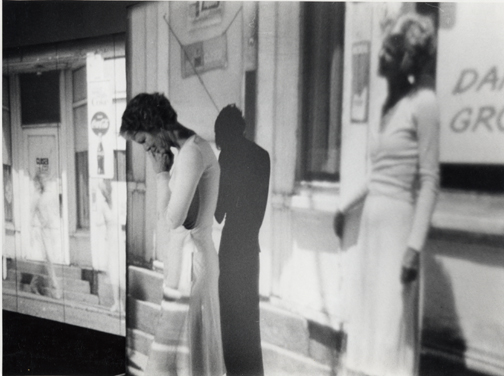

Davies expands these ideas further in “Small Circles, Great Planes,” in which live Cowles was joined by dancers Jodi Melnick and Neil Greenberg. Also a triptych, this work’s filmed images include cement grain silos juxtaposed with birch trees, Cowles and two uncredited dancers walking into a pond, and the trio at a storefront (whose sign hilariously reads “Ice, Dancing, Groceries”).

Against the filmed background, the live performers reflect the movements of their predecessors. They strip off the vertical fabric panels of the screens, and dart in between the openings. They change into the white cassocks of the filmed performers and walk, arms clasped between their backs, in monastic union with their images and the black silhouettes sandwiched between filmed image and live performer.

In the end, what these film performance pieces reveal most clearly is the essence of their creators: Davies’ fascination with structure, layers and process; Cowles’ openness and pure joy in movement; and the places in time and space in which the two boldly continue to meet.