Space Exploration: MCAD/McKnight Visual Arts Fellows 2008-09

Mason Riddle reflects on the fruits of a year of practice by the 2008-09 McKnight Visual Arts Fellows -- Jennifer Danos, Janet Lobberecht, Margaret Pezalla-Granlund, and Megan Rye -- on view in the MCAD Gallery through August 12.

IF THERE IS ANY SPECIFIC CONCEPTUAL PURSUIT THAT LINKS the current McKnight Visual Arts fellows, it is their investigation of space in its many manifestations — physical and psychological, known and imagined, interior and exterior, and remembered and forgotten. In her essay on Jennifer Danos, the exhibition’s catalogue author, Dr. Jane Blocker, cites the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre (1901-1991), quoting from his important work The Production of Space (1974), “We are concerned with the logico-epistemological space, the space of social practice, the space occupied by sensory phenomena, including products of the imagination such as projects and projections, symbols and utopias.” For Lefebvre, every society produces a certain kind of space, its own self-identifying space, one of “social existence.”

Jennifer Danos has built a practice on creating conceptual works from marginalized, unnoticed, taken-for-granted spaces. In her 2008 installation, Architectonic Obtrusion, at Franklin Art Works in Minneapolis, she created a wedge-shaped grey concrete plinth on FAW’s grey concrete floor. Maneuvered/fitted tightly between a wall and the gallery’s central column, not only did the angled slab support nothing, it seemed to be without purpose at all. Simply, the piece visually interrupted the space by laying down another physical layer of uninflected material, while disrupting the viewer’s expectations and perception of the space. For the current exhibition, she has claimed the recessed baseboard of a gallery wall, onto which she has projected, in black and white, waves of flickering light. Untitled (Imagined Extensions 1&2) is easy to miss, due to both its pedestrian location and subtle perceptual presence, but it makes exotic that peripheral space we often miss, an understated embodiment of Lefebvre’s “space occupied by sensory phenomena.”

In her site-specific installation, Untitled (median claim), Janet Lobberecht has created a spectacle of space appropriation. Using the grassy median at the center of the turnaround drive at the College, Lobberecht has raised a flagpole, upon which flies a banner bearing a central green rectangle bordered by a thin yellow stripe and a wider black border. The flag gives the appearance of colonizing the space, yet its import is little more than a visual echo of the geometry of green sod, painted yellow curb, and black asphalt drive beneath. Lobberecht’s blank green, yellow, and black flag is a passive, rather than active marker of claimed space. The piece seems to signify the futility behind the notion of permanent land ownership, as it claims an active proprietary interest in virtually nothing — it’s a symbol without value on a nondescript plot of land, far from any sort of utopian ideal.

Similarly, Lobberecht’s X (nothing but) seems to evoke Lefebvre’s “products of the imagination such as projects and projections,” but again, in a subversive manner. Here, she creates a tableau, but as with the previously mentioned piece, its meaning is askew: next to a leafy green potted plant a red floor lamp shines brightly on a white wall, mounted only with a piece of beige carpet. On the floor, before the carpet remnant is taped a black “X” and on the wall is a blank brass nameplate; the carpet remnant behind the wall is equally empty of meaning, no more than just what it appears to be. The “X” marks where the visitor is to stand, presumably the best vantage point, yet there is little of purpose or meaning to contemplate once you’re in position, only banality.

______________________________________________________

If we are told that an image depicting, say, a walk on the moon, is true — how do we know it? Did the event pictured really happen? Is the viewing of such an image, alone, proof of fact?

______________________________________________________

Lobberecht’s The Whole and the Nothing But is more performative, an apt depiction of Lefebvre’s “space of social practice.” On a monitor, various individuals move or dance in repeated cycles of motion, while various declarations scroll across the screen: the Hippocratic Oath, an oath of office, a marriage vow. Recalling the declarative statements central to works by Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger, and the repetition of movements by participants in Bruce Nauman videos, The Whole forces us to consider the power and control of such supposed societal promises — ‘one nation under God’, ‘to have and to hold until death do us part’ — are such statements true? As Dr. Blocker states in her catalogue essay, “[Seeing Lobberecht’s installation] we wonder about the speaker’s sincerity and truthfulness: about the tradition of the oath…and about the authority of the speaker…”

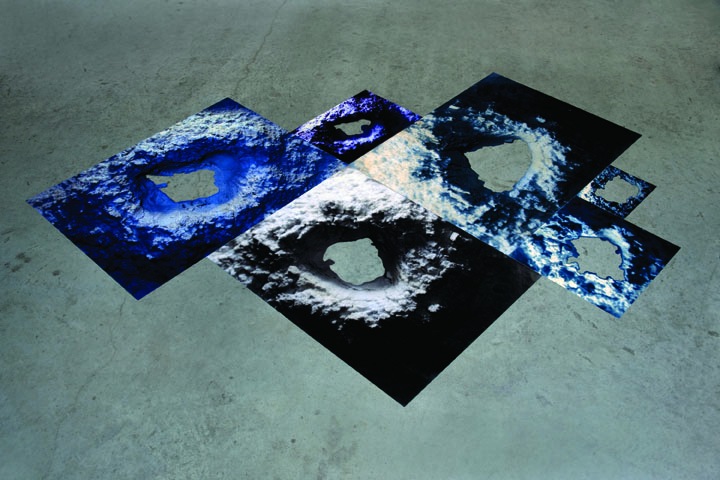

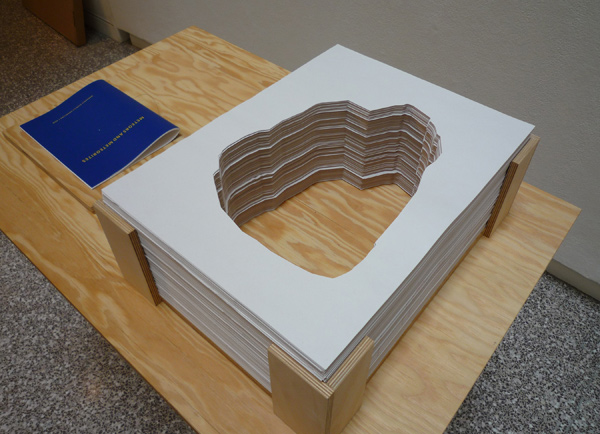

Margaret Pezalla-Granlund raises questions, too — about seeing, knowing, and knowledge production, using both the abstract receptacle of space (literally, outer space), as well as the literal space of the MCAD gallery. With the recent celebration of the 40th anniversary of humanity’s first walk on the moon, Pezalla-Granlund’s current body of work is apropos, in that it uses images of rocks (asteroids? meteorites?) to explore our ability — and faith — to belive the “truth” before our eyes. If we are told that a photographic image depicting, say, a walk on the moon, is true — how do we know it is so? Did the event pictured really happen? Is the viewing of such an image, alone, proof of fact? This is not a new intellectual inquiry, yet Pezalla-Granlund effectively prompts us to the question anew: are her depictions true – are they real meteorites? And, more, in what sense do they represent real knowledge?

To underscore her inquiry into this idea, the artist has folded photographs of rock into 3-D, sculptural meteorite-like shapes, titled Fall (Hahn), that are suspended from the gallery ceiling like a small cosmic storm. Other 2-D photographs of rock with cutout centers, like doughnuts and their holes, collectively titled Fall (after), are placed carefully on the floor. In another work, Absent, a deep stack of sheets of newsprint has been eviscerated with a meteorite-like hole at the center; the stack is placed authoritatively next to a slender booklet titled Meteors and Meteorites, (authored by Pezalla-Granlund) as if it were a display in a natural history museum. This supposed body of evidence, as if a virtual re-enactment, is undermined by a series of jewel-toned watercolors of meteorites, titled Unidentified Meteors (distant) a dreamy, poetic rebuttal to the proffered truth of the photographic images. Which is actually more real? What depiction is more truthful? That is, is what we see in Pezalla-Granlund’s tableau of photographic evidence in some sense truer than her shimmering watercolors?

In addressing Megan Rye’s work, Blocker precedes her essay with a quote from Derrida’s influential ideas about the abstract notion of the archive: “But where does the outside commence? The question is the question of the archive. There are undoubtedly no others.” Much has been written recently about Rye’s unsettling paintings of the war in Iraq, created directly from an archive of over 2000 photographs taken by her brother Ryan, who was a U.S. Marine in Fallujah. These haunting, uneasy photo-based paintings take on an eerie beauty, depicting the literal, physical space of war and its inhabitants — the desert, the interior of land vehicles and airplanes, weapons, barracks and servicemen — not to mention the emotional and psychological space occupied by action, memory, fear, relief, determination, light, color, and sound. Yes, Ryan’s photographic archive consumes literal space, but its information and record of events elide into, even overwhelm, another kind of territory that is at once conceptual, visual, and visceral, onto which Rye layers a dramatic space of color, intuition, and aesthetic response. As Ryan’s literal record of the daily activities of war is re-imagined through Rye, a unique universe, an archive once removed but perhaps equally as real, is created.

As with most juried fellowship exhibitions, there is not a unifying thread of style, content, or practice that connects the work in the 2008-09 MCAD/McKnight show. However, linking all of the work is a conceptual practice, exercised by all four artists, a practice that consistently leads back, through unique aesthetic modes, to ideas and questions about formal and abstract notions of space.

*****

Related exhibition details:

MCAD/McKnight 2008-09 Visual Arts Fellows’ Exhibition: Jennifer Danos, Janet Lobberecht, Margaret Pezalla-Granlund, and Megan Rye will be on view at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design Gallery in Minneapolis through August 12, 2009.

About the writer: Mason Riddle is a critic and writer on the arts, architecture, and design.