So Good, It’s Almost Eerie: McKnight Fellows in Photography

Michael Fallon reviews "New Photography: McKnight Fellows 2003 + 04: Terry Gydesen, Celeste Nelms, Xavier Tavera, Katherine Turczan," at the Katherine Nash Gallery, through September 30.

After recently slamming the other yearly McKnight extrava-bition (see link below), I asked myself why such big and costly and highly anticipated shows generally tend to suck ass (or, to put it more politely, why the sum of the parts of such shows never seem to amount to the potential whole). My first working hypothesis came out of an examination of the way such fellowships are awarded. That is, typically the foundations gather up a jury of diverse art experts (which raises the plaintive question: Why have I never been asked to participate?), and the jurors proceed to choose the fellowship winners and show participants via consensus vote.

Aha! I said to myself. So that’s what’s wrong. Obviously, since an elite and disconnected body is making a group decision on who wins the fellowship, then this explains why the work tends toward the namby-pamby, the trendy, the watered-down and safe. There’s no room for unconventional, literally exceptional art when the jury is a diverse bunch of stuffed shirts looking to select a representative sample of artists. Representative democracy, as we all know from experience, does not tend to choose good art for itself–it chooses Norman Rockwell and Thomas Kinkade. Only true eccentrics like Peggy Guggenheim or Charles Saatchi can make un-popular and visionary choices about art.

Thus buoyed with my insight I marched right into the Katherine Nash gallery this week to see “New Photography: McKnight Fellows 2003+04.” I was set to pounce like charcoal all over the show. And alas, I have to report that despite my desire to prove myself right the show promptly knocked my notion right on its ass.

This show is great (with the exception of the exception I take with the Nash space, where the lack of intimacy is oppressive generally; but I’ve written about that before, so I’ll leave off). The four exhibiting fellows–Terry Gydesen, Celeste Nelms, Xavier Tavera, and Katherine Turczan—give us an honest and good sampling of their exception personal visions. The whole of the show is connected (despite the twisting sprawl of the space—oops, promised not to talk about that) by the quality of the work and the willingness of the artists to stretch their efforts. I am particularly pleased to report, too, that each artist here has taken risks when it wasn’t even necessary for them to do so—as they all were rather well-celebrated locally even before they got their McKnight checks.

As a case in point, Celeste Nelms for example works a new angle into her work—something only slightly explored in her show last year at the MIA. Whereas before she took pictures of herself in sepia-toned spaces, usually outdoors, holding some old tossed-off and discarded (but found) object, here she incorporates such objects into small installations of her photographs. Among the things on display with her photographs are picture frames from another, more gaudy era; a doll house filled with teeny-tiny samples of her photos (and a tiny camera!); a buffalo plaque; a picture-window clock; and a Viewmaster. While not all of these kitschy moments work, at least it shows an artist unwilling to rest on her laurels.

As before, her images range here from the uncanny to the hilarious. In one weird photo called “Skates” (2003), a woman walks barefoot on what appears to be a dirt-street ghost town—the Ben Franklin and other shops to either side of her inaccessible and empty. In a more humorous shot, the woman sleeps in the hand of a large fiberglass Paul Bunyan. In a photo both humorous and eerie, a blurry woman appears in what looks like a graveyard of cars—all planted headlong and sideways into the ground.

There’s a possibility that some sensibilities might find these objects and the way the artist poses with them a bit precious. I’d argue, however, that Nelms’ penchant for memorable iconography of a pure middle Americana —bowling trophies, spin wheels, American flag scarves, a stag head, and bowling pins all make appearances in her photos—reveals an almost anthropological quality to her work that takes it beyond preciousness.

Katherine Turczan’s images, meanwhile, are powerful and revealing. She has four untitled images in the show—three presented as a kind of triptych, and one that stands alone. The imagery is alternately of little prepubescents in various stages of undress and dead birds. The stand-alone is good if you were interested in knowing, say, what a crow’s talons looked like up close. The image is beautiful and exquisitely detailed, and disconcerting. The bird is big— about the size of a medium-sized dog against a black background.

At the same time, the diptych is a little obscure to me. In the left-hand photo a nude cherubic little is depicted from the fanny angle, holding a fancy parasol in front of her/him (it’s unclear which). In the middle is another highly detailed dead bird—this one looking like a sparrow. And on the right, a half-naked child hides his (or possibly her) face behind a birdlike mask. Is it just a matter of examining the fragility of life? The sanctity of life? Obscure sexuality? The way children are not much different from little birds? Though it doesn’t seem to amount to much conceptually, at least in my reckoning, the imagery is still powerful and memorable.

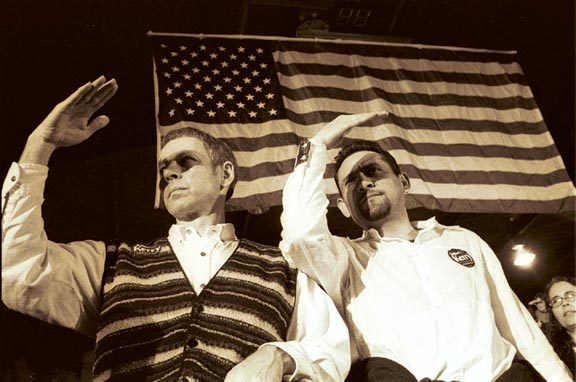

Terry Gydesen’s work also lacks conceptual pretensions, but is no less interesting for its flatfootedness. In an expansive series of smallish photos, Gydesen documents the inner workings of days and nights at the Capitol in Saint Paul during the last session (in 2004). This work resembles another local photographer of note, Paul Shambroom, in that it reveals the deep psychology of moments and spaces that exert an abstract power and control over our lives (though the functioning of government or other such ruling institution). Gydesen’s work, however, is more immediate, less long-term, and more photojournalistic (and less artistically refined) than Shambroom’s.

In most images, Gydesen gives grainy snapshot views of behind-the-scenes moments in legislative subcommittees, legislative offices, and inside the Capitol and on its steps. Interestingly, the whole seems to amount nearly to a narrative of the legislative process, as characters such as Senators Mee Moua and Scott Dibble reappear and exhibit changing moods and postures, as the scenes range from the frenetically public to the poignantly private, and as we see the wide expanse of the process from internal subcommittee meetings to public demonstrations. Among the most memorable of all of this mass of memorable images is “Death Penalty for Homosexuals” (2004), in which a black-jacketed and disheveled hunk of a man at a Capitol rally holds a sign, with rather blasé aplomb, that suggests exactly what the title says–giving one pause to wonder about it all.

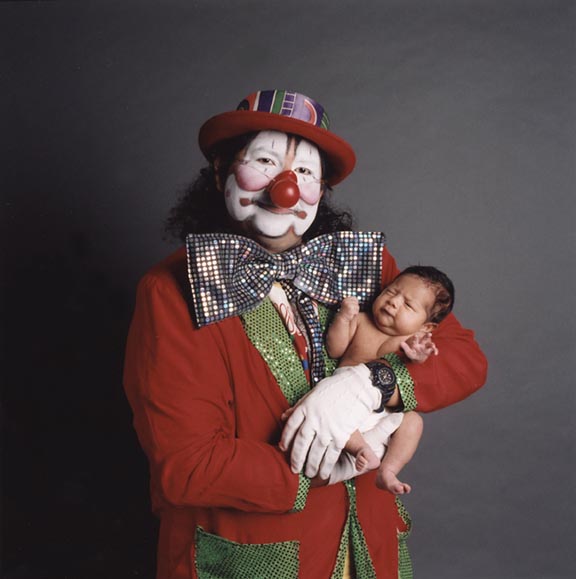

Finally, speaking of blasé aplomb, we have the work of Xavier Tavera. Tavera turns photographic examinations of identity—mostly of Hispanic or other ethnic men—into a compelling practice. A series of large works on canvas here, titled collectively “Tierra Atraz Series” (2003), are icons of the modern church of militantism. These images are charged with symbols and bold colors. The men are all shot from just below the waist up, and each holds a baby in much the way of a Renaissance Madonna. The get-up of the men is a clue into their psychology, as are their eyes—sometimes the only thing revealed on their faces. There’s a clown here, a welder, a mujahedeen, a Zapatista-type, and a la raza gangster. Adding to the sublime confusion is the changing color of the baby—sometimes he’s dark-skinned, sometimes light, sometimes in between. All of which leaves me with whole bunch of questions I’d like to pose to the artist—and I mean that in a good way.

Also included in the show is another, more recent series of smaller photos by Tavera that I find a little less interesting. The whole Mexican wrestling thing—with scratched-up and bleeding wrestlers and old and young referees and so on—doesn’t really grab me much beyond a simple curiosity about the subculture. It doesn’t pose as many questions as the Tierra Atraz work.

So. With the above evidence I’m just about back to the drawing board regarding this issue of the suckyness of the foundation-fellowship greatest hit-type shows. Unless of course you’re willing to grant that the above show is the exception that proves the rule. Or, better yet, perhaps it has something to do with the quality of local photographic artists—which at times seems so far beyond that of local artists of other mediums to be almost eerie.