Seeing “Six McKnight Artists” at the Northern Clay Center

Mason Riddle calls this show of 2008 McKnight fellows' new work in ceramics "one of the most compelling of its kind in recent memory."

Exhibitions of work by fellowship artists can be rough on the eyes. Rather than being curated for style, content or cultural point of view, such shows are simply the result of an award system by an outside jury, an exhibition of various aesthetic practices rife with potential to create one visual, cacophonous clash. Not so with Northern Clay Center’s Six McKnight Artists, though. In fact, the show at NCC is one of the most compelling group shows of ceramic work in recent memory; there is not a dud in the group. Offering up entirely different aesthetics and ways of working with the most humble of artistic media, what one artist called “dirt”, the expansive exhibition features work by Greg Crowe, Andrea Leila Denecke, Marko Fields, Lee Love, Margaret O’Rorke and Alyssa Wood. The collection on view is a testimony to the breadth, depth – and sophistication – of ceramics, all but eliminating that slippery distinction between the craft and fine art. (Corroborating that position is the fact the show is titled Six McKnight Artists, not “Six McKnight Ceramists”.)

Awarded one of the three-month McKnight residencies, the British-born Australian resident, Greg Crowe, has made impressive aesthetic and technical leaps since I first was introduced to him and his work in 2000. His stoneware, wood or soda-fired vases, bowls, jars, and plateau dishes are visceral pieces that push the notion of a functional pot into the realm of highly manipulated sculptural forms. The ghost of Voulkos lurks among the pieces on view. These are Extreme Pots, whose function takes a backseat to form and surface. Edges are uneven and rough, and the works’ tactile surfaces are an amalgam of crude surface decoration — swirls, striations, bumps, blisters and webbing — that suggests the works have just been unearthed from some long-lost, less technological time.

Andrea Leila Denecke’s bold, architectural soda-fired stoneware with granite inlay is more sculptural than functional, too; yet the pieces have an implicit refinement and elegance about them. All about edge and surface, her slab-constructed work is influenced by Asian ceramic traditions, with a nod to a Japanese architectural aesthetic. Proving the point, vase-like works are titled “Ikebana Vessels”. Many are closed forms composed of unique, shifting geometric planes, reticulated with small openings or sporting vernacular-style roofs. Although of good scale, the works suggest an even greater monumentality due to the simplicity of their forms and impenetrable surfaces. In contrast, her wheel-thrown Younomis (cups) are diminutive, graceful, and animated.

The elegance and simplicity of Denecke’s work is countered by the complexity and narrative qualities of Fields’s passionately decorative, figurative pieces. Passionately gonzo, that is — his are the Heavy Metal of the ceramic world. Fields leaves no surface untouched. These pieces veritably scream, “Over here, quick. Look at me!” And look you do. Technically demanding and labor intensive, each sculptural work — even if it masquerades as a teapot, oilcan or plate — is a roiling concoction of figures, animals, sculls, crossbones, text, abstract symbol, often realized in brilliant Technicolor. Once acclimated to the visual onslaught, the viewer soon realizes the majority of the work explores issues of environmental degradation. Two-headed frogs and skulls play off the names of major corporations, such as Dow, Exxon and Chevron, or brand-name pesticides. A grand mix of social commentary and pop art cum comic book aesthetic, Fields’s work is commanding but exhausting.

The Six McKnight Artists exhibition is a testimony to the breadth, depth – and sophistication – of ceramics, all but eliminating that slippery distinction between the craft and fine art.

Operating in a completely different aesthetic sphere than Fields, Lee Love is represented by 55 tea bowls, one for each year of his life, some of which come with their own handmade wooden box. Love, who was born in Japan to an American father and Japanese mother, has combined the best of both cultures to create functional work inspired by the Japanese folk-art tradition called Mingei. After growing up in Michigan, Love came to Minneapolis in 1983 to study with a Zen master; with his master’s death, his educational focus turned to ceramics. In 2000, he moved to Mashiko, Japan to apprentice with the Mingei master Shimaoka and, later, to start his own pottery. He returned to Minneapolis in 2007, where he now makes his home after being awarded his McKnight residency. Love’s bowls are all elegant yet understated. Despite their installation together, it is possible to conduct a unique visual conversation with each, learning about subtle variations in scale and surface treatment, as well as the power of such a simple form.

Another McKnight residency artist, Margaret O’Rorke, is a native of Great Britain who lives in Oxford; her work seems a wholly original vision for working with clay. Suggestive of handmade paper more than cast porcelain, O’Rorke’s Ice Mountain lamps carve out a unique place in the world of ceramic art. Illuminated from within, the pointed, craggy lamps, when displayed en masse on a large pedestal, poetically recall an army of animated stalagmites. (For some reason, seeing them I also started to think of Fantasia‘s dance of the broomsticks.) Remarkably, the light dissolves the crisp rigidity of the porcelain, creating a transparent aura that is palpable. O’Rorke’s thrown chandelier is equally impressive — its hanging porcelain tendrils evoke the curving tusks of a sea lion.

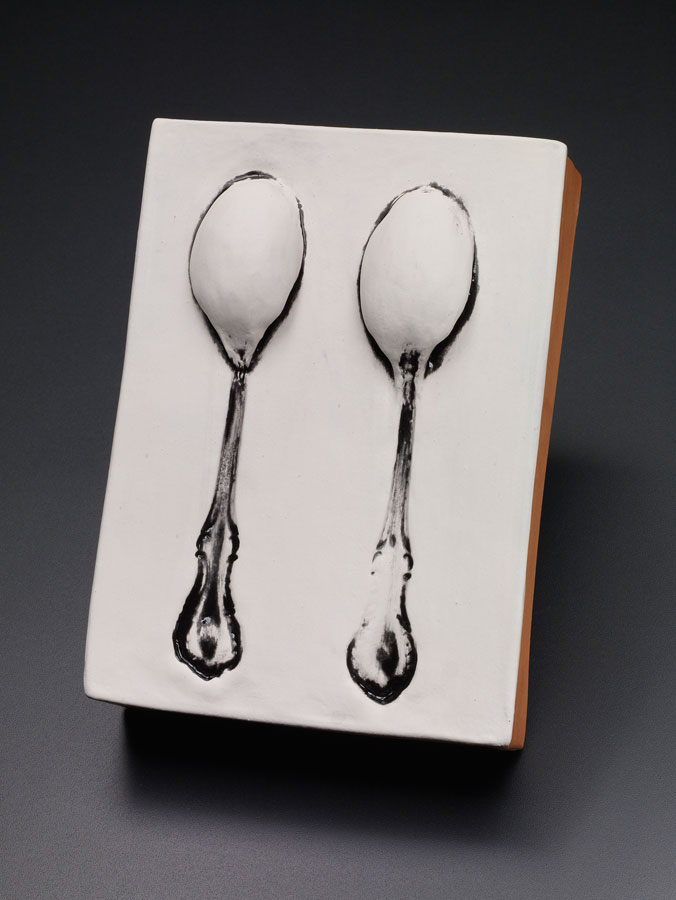

During her residency, North Carolina resident Alyssa Wood created a conceptual, pop-art body of work whose lineage threads back to Jasper Johns and even Andy Warhol. Using domestic situations as her context, Woods has created thick earthenware tiles: on some, she paints — with terra sigillata, washes, or glaze — representations of such mundane objects as a bathtub, laundry basket, scissors, or a birthday cake in a loose, hurried brushstroke. For others, she creates a bas relief tile of a spoon with a thick blistered and cracked surface. Some of these works of ennobled domesticity are paired with tiles depicting counting systems, such as Fibonacci sequences, creating an odd but compelling formal relationship between the two. Wood’s are seductive, ultimately elegant little pieces whose ostensible ordinariness belies a sophisticated conceptual resonance.

It is no small feat to install nearly 150 disparate works in such a way that the viewer can make visual sense of it all. But the work of Crowe, Denecke, Fields, Love, O’Rorke, and Woods is enhanced, not compromised, by the thoughtful installation by NCC Exhibitions Director and Curator, Jamie Lang. Taken together, the assembled collection makes for a compelling, coherent exhibition. Each artist and each piece is given its professional due, elevating the show to must-see status.

Exhibition details: Six McKnight Artists will be on view at the Northern Clay Center in Minneapolis through July 5. Visit the gallery website for hours, directions, and addition background information on the McKnight residency program and the fellows featured in this show.

About the writer: Mason Riddle is a critic and writer on the arts, architecture, and design.