Second Skin: “Marked Men” at Rogue Buddha

Suz Szucs visited the "Marked Men" show at Rogue Buddha Gallery in Northeast Minneapolis (357 NE 13th Avenue) just before it closed. Here's her take on this fascinating show; for more, click the link at the foot of the article.

“Marked Men” at Rogue Buddha gallery represents the fine art work of some pretty big names in the tattooing world. Some of them were responsible for the tattooing renaissance in this country, which started in the 1960s and hit its peak during the 1990s. Before that time American tattooing was incidental, working-class, and coarse compared to the elegance of non-Western body art. American tattooing consisted of collected marks, often barely considering placement on the body. Asian and South Pacific tattooing or scarification on the other hand worked with the body, calculating where the mark might fall upon it, how it was incorporated into it and often added to the recipient’s spiritual identity. The Maori Moko was a ritualistic cultural mark; the Indonesian tattooing was a five-day ritual where the mark was pounded into the body at the risk of death; Japanese spent decades collecting their full body tattoos, some donating their skins to museums: once-living art.

The artists in this show took what they learned from non-Western sources, combining it with their love of American style to create a radical movement in tattooing – making art on the body. The work in the exhibition represents the attempts of these tattoo artists to work off the body and into fine-art mediums of painting and sculpture. Mostly flat work, at times it feels primitive and raw, at others tight, missing skin. How does one translate into two dimensions ideas that seem so comfortable breathing on a fleshy surface? Why leave the skin behind, when it is so integral to the art?

Of the artists in the exhibition, Thom deVita’s colored pencil and ink markings on board feel the most primitive – the most related to traditional American tattooing with simple symbolic imagery. In places the color is caked on the board with a waxy buildup; mistakes are made and covered up – something you cannot do on skin. But the wood of the panel itself that is fleshlike, with a variety of texture, surface, and color. There are places where the ink sinks into it, absorbed. When this happens, it feels as though a piece of skin has been stretched out. As fine art pieces, they are not fully realized compositions, but the relationship between mark and substrate is satisfying.

Tyvek is one of my favorite materials. It has suppleness and strength. Contractors use it to cover houses, I use it to wrap my own art, Don Ed Hardy has used it as a canvas. His large ink paintings are tacked unframed on the wall. They feel naked. Compared to the other artists in the exhibition, his work feels almost out of control. It is messy and takes time to make sense of. Only his work feels far away from the world of tattoo, although one can find many references to that art form if time is spent with the work. Moreover, these images are about the body and sexuality. Jungle Liberties is a cacophony of body parts ejaculated onto the canvas – skin, balls, engorgement – it is refreshing to see male sexual expression on display in a manner not clean or refined or reliant upon the female (especially within the context of tattooing, which has been notorious for its graphic misogyny).

His smaller pieces feel claustrophobic, breathless. They are best viewed from a distance, where the huge strokes and graphic dips form into Asian dogs and dragons. Now and again a grounding image emerges from the ejaculation of black – fire, sun, teeth. His wash of color creates a shading and depth that the powerful, shaped line craves. Their mess, their seeming hurry rewards the viewer for time spent.

The assemblages of Nick Bubash are tattoo made three-dimensional and the most compelling work in the show. He creates new creatures with found objects, decorates them, deconstructs them and ultimately creates fantastical narratives. His designs are rather simple and symmetrical, but what he does within that construct is thrilling. They recall the mobile creations of Lee Bontecou—but where her images feel like weightless space villages, Bubash’s pieces have an earthy quality. They contain a carnivalesque physicality that is appropriate to the corporeal world of tattoo.

The central image of St. Bozo features an altar Virgin Mary with a clown head, still full of compassion, and a fruit globe reminiscent of the late great Carmen Miranda (remember Chiquita Bananas?). It is not that religion is being mocked, but that the delight and wonder of faeries, of a virgin mother, of clowns and carnivals, of sticking pins in bugs, is the true foundation for our faith. Play makes life bearable, and if nothing else, this man wants to play.

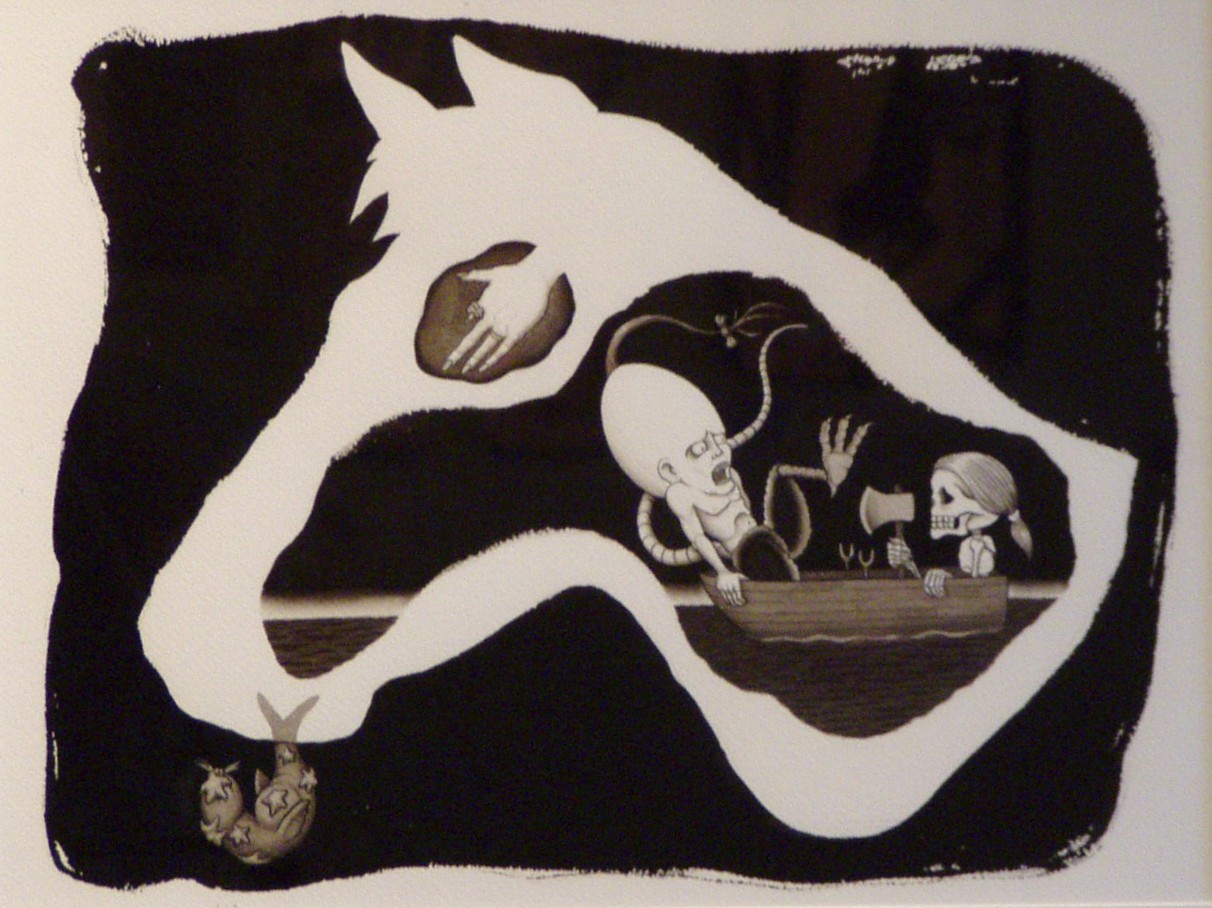

Scott Harrison also creates a sense of narrative. Very tight ink drawings, his small images are nightmare visions. Where Hardy’s work is messy and sensual, Harrison’s is precise, controlled, and macabre. When he is strongest, he uses positive and negative space in fluid tandem and the ink creates heavy forms. His work crosses into the realm of graphic novels, a form whose recent vogue in America has paralleled tattoos.

Despite Harrison’s graphic precision and stellar technique, because all his work is untitled, his narratives remain mysterious. Death, mortality, and fear pervade it, and although the images feel cold, the body is present conceptually, most clearly expressed in an image of Death cutting off his own flowering erection. The content of the most obvious image is that of a top-hatted pig, swallowed by his own labor and cannibalizing himself or others to get ahead. Harrison is using the style and technique of tattooing to express concept, he clearly has a passion for American-style flash, but could use more context to bring the viewer past the bizarre.

Mike Malone presents work that is almost all narrative. His silver and gold ink images on black paper reference Asian landscapes and make me ruminate on the relationship of the body to environment. His Ghost Kanji are beautiful images, but very distant from the other work in the exhibition, which offers a corporality that is missing from this work. Their presentation needs more breathing room than they are allowed; they compete with a sculptural piece sharing their small wall. Malone needs to stretch himself onto larger canvases, at least approach the size or form of the body. Compared to the other work in the show, these pieces feel precious and quiet.

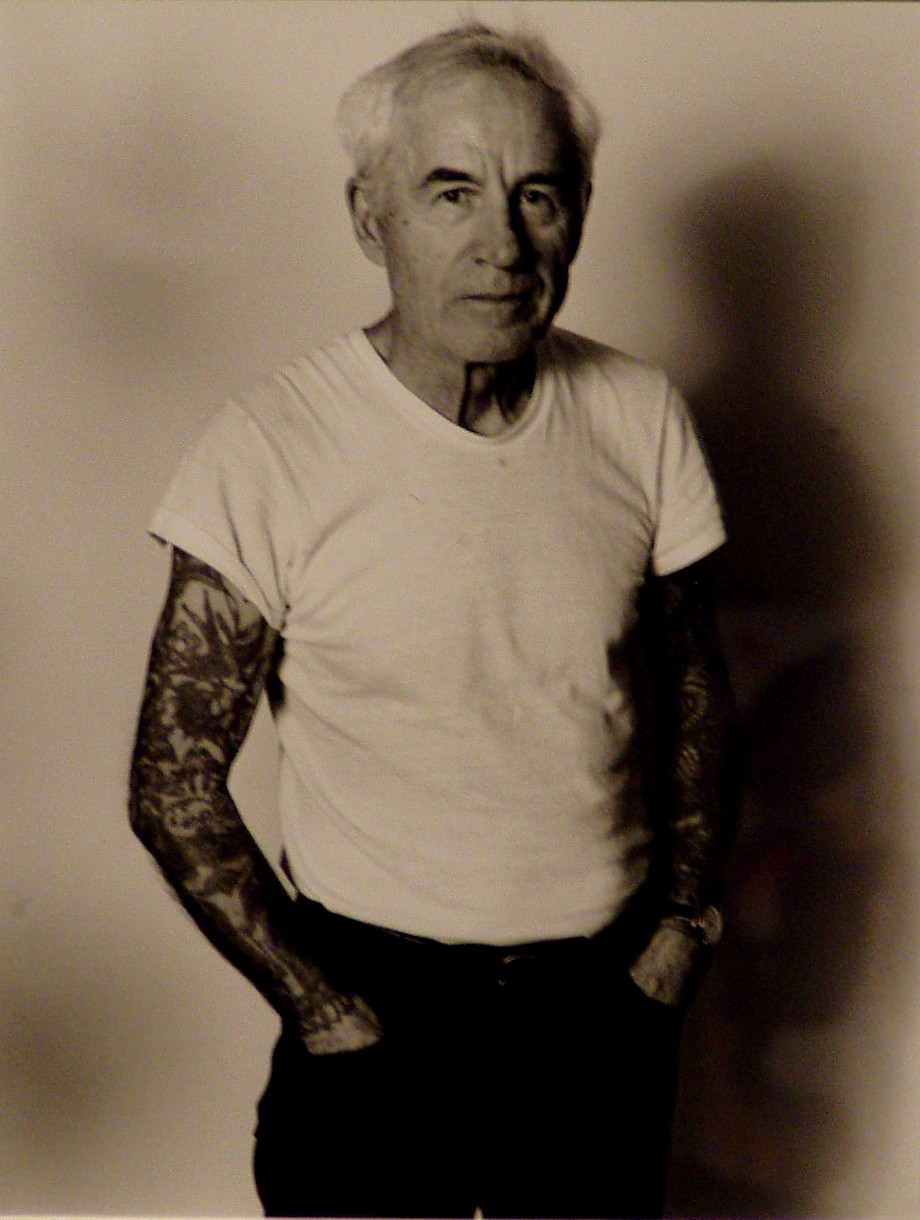

As presented in the exhibition, Bob Wyatt’s photography plays like an addendum. Whereas the other artists are attempting to translate their body practice onto another medium by referencing the influence the corporeal has had on their thoughts and expressions, the photographs are documents of tattooists and don’t have the conceptual leanings of the other work. They are important documents, however I would like to see them presented in another room, informing the main exhibition, but not interfering with it.

Marked Men represents a group of image-makers who are tremendously successful in one world attempting to cross over into another. They are bringing a popular art form into the gallery and like graffiti in a white space it is a problematic translation when it feels like the foundation of the work belongs not in the museum, but the streets. As a viewer, I try to imagine what sense of satisfaction or resolution these artists get from making this work, when on a daily basis they have live bodies to work with. Perhaps this gives them an opportunity to free themselves from being collaborators, celebrating their ideas independently from the person who might wear their creations.