Saturday Is the New Monday: Pear Cowboy Planet

Lightsey Darst describes the third of these outings at Bryant Lake Bowl: look for the fourth and last in short order.

Saturday is the New Monday Series:

“Trilogy: Pear, Cowboy, Planet” by T. S. K.

at the Bryant-Lake Bowl Theater

If you’ve been awake for any length of time in the art scene lately, you will be able to guess at the mood and style of “Pear Cowboy Planet (a trilogy)” by T. S. K. simply by looking at the title. You should guess that T. S. K. will be cleverer than you, such that at some point you will envy them their hip, witty youth, after which you will begin to dislike them. You should guess that T. S. K. will make wild associative leaps and include strange objects, like toasters painted yellow, in the unexplained yet significant background. You should guess that T. S. K. will use a variety of music, some barely there, the sound of one cricket scratching, some raucous, and some aggressively lo-fi bordello piano tunes. You should guess that “Pear Cowboy Planet” will not add up the way those silly math textbooks and after-school specials once told you things would. In all this you’ll be right—except that the yellow objects parked so insouciantly at the back of the Bryant-Lake Bowl stage are vacuum cleaners.

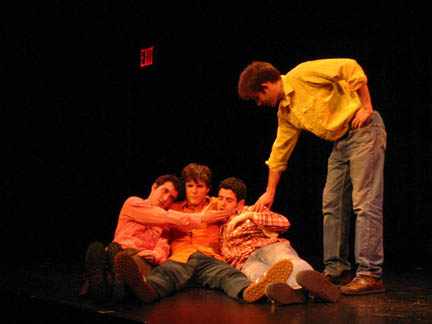

We’ll get back to these predictably unpredictable elements in a second, but first, what you wouldn’t guess is the talent and intensity of the performers. T. S. K. is a Faribault-New York crossbreed, which is to say that it’s composed of young artists who mostly used to live in New York, a few of whom presently live in Faribault. New York shows (I’m guessing) in the completeness of the performance and in the performers’ ease on stage. It’s not that we don’t have skilled performers here, but few, as yet, look so comfortable being so postmodern—yelling, acting, speaking, contorting—on stage. Minnesota performers often have the slight edginess of knowing part of their audience will think they are just being silly. All the leading performers—Justin Jones, Chris Yon, Jeff Larson, and Zach Steel—are not only comfortable with being absurd, they are also good at it: good at posing, staring glumly or pensively or coyly into the audience, good at taking up odd characters and caprices. There’s also a thrill, tinged with danger, in seeing four young men stampeding and hurling each other around on the Bryant-Lake Bowl’s tiny stage.

The other element you might not guess is the latent content, hiding under the surface less like a cherry in a bon-bon than a straggly crab in a fish tank. In the longest of the three pieces, “Cowboy,” Zach Steel constantly tells all the other performers what to be and how (“Chris, you be Cowboy; put your hands in your pocket; no, both hands in one pocket, like a cowboy does”). This obsessive self-construction suggests some denied, deferred grief. Later we find out, through an argument between Steel and Jeff Larson (in the persona of Angry Dad), that the denied grief is “Mom has cancer.” “I know, Dad, I know,” replies Steel. In a moment Steel and Larson are back to clowning, but the sad undercurrent remains. When the Zambonies, a group of mostly female dancers, come out to clear the stage, they perform a rapid, cheerful hari-kiri, smiling all the while. Later Mom’s cancer, that gnawing, potential grief, seems to be the subtext for Jones’s shaky, anxious solo “Planet.”

If grief is the subtext, though, it’s more the surface that we see—the jittery, ironic, postmodern surface referred to above. The style gets explored here, not the subtext, which never moves or develops beyond its first appearance. Perhaps that’s the intention: T. S. K. wants us to see how people dissimulate their grief. But I have to admit that I’m unconvinced by child’s play, obsessively repetitive movement, and irrelevancy as a portrayal of life (in whatever removed sense). There certainly are people whose lives resemble those of domestic chickens—scratching, pecking, running around mindlessly—but I don’t find those people interesting. In other words, I’m bored when performers repeat the same movements over and over again, each time with greater amplitude, as frequently happens in “Pear Cowboy Planet”. After two nonsense jokes, I can’t be surprised, and I stop laughing. Neurosis and the non sequitur are the wall T. S. K. keeps hitting; the performance, for all its variety, is mostly monotone.

After a while, I found myself watching this performance subversively, on the look-out for any moments of beauty or real, not coy, vulnerability. There were some: Justin Jones, in particular, occasionally spins into expansive, energetic, yet mannered beauty, his hands and feet the slightly turned edges of a whirlwind. These moments were possibly planted there on purpose by T. S. K. As I said before, they’re clever, and they may have been playing me all along, intending to baffle and frustrate and then reward the viewer with a few snatches of emotion and sublimity. But I think it’s more likely that Chris Yon’s early monologue is accurate: comfort and wild, native beauty, in the postmodern realm, are at odds, and T. S. K. chooses this ironic, irrelevant, anxiety-riddled comfort.