Rising and Falling to the Occasion: New Photography, McKnight Fellows 2004-05

Glenn Gordon went to the McKnight Fellows show just before it opened, and filed this review soon after.

The day I went to see New Photography: McKnight Fellows 2004-2005 at the Katherine Nash Gallery in the U. of M’s Regis Art Center, the catalog to the show was not yet back from the printer. It was good, in a way. It meant there was one less thing between you and the work before your eyes. With no writer there to shepherd your thoughts, and no “didactics” on the walls, the photographs were freer than usual to stand or fall on their own. Nothing obliged you to look further than you could see by yourself–the pictures speak to you or they don’t. Language creeps in soon enough, but before it does the work is naked and so (for a short moment) is your mind—or at least so I would like to pretend.

The question I kept feeling as I went through this show was “Does this picture hold up on its own or does it need an armature of explanatory rhetoric for me to get it?” The answers went both ways. The four McKnight Fellows this year are Beth Dow, Alec Soth, Tobechi Tobechukwu, and JoAnn Verburg. Each of the four exhibits at least a few works that feel to me self-contained, in this sense of being able to stand free of talk. None of them succeed at the difficult feat of doing it consistently but each photographer shows at least one or two pictures that set a benchmark to which the rest of his or her own work could aspire.

To me, the work in this show that comes closest, as a whole, to embodying this relatively unmediated state is the group of black and white platinum-palladium prints by Beth Dow, formal photographs of English palace gardens, some with classical statuary of such figures as Ceres, or the Dying Gaul, or urns decorated with sphinxes and leonine grotesques. The very stillness of these pictures’ subjects quiets down the air around them. Finely crafted objects in ebonized wood frames, the prints have a slightly warm vintage cast, the platinum-palladium process embedding the subjects in a kind of amber. Serenely composed images of serenely composed places, the works are not exciting (a few are downright static), but they are beautiful to contemplate. My favorite is “Benches, Blenhheim Palace,” the first image encountered as you approach Dow’s part of the gallery and the only picture in the group with a living human being as one of its subjects.

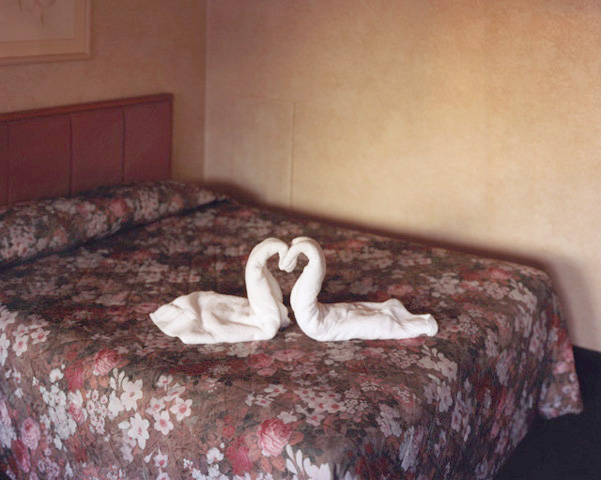

Alec Soth portrays twenty or so human beings in his sector of the show, a project documenting Niagara Falls, but how humanely they are portrayed is an open question. Only a few of Soth’s photos hang on the gallery wall, but there is a leather-bound book of the project with about 35-40 prints that sits on a lectern adjacent. In it, Soth indulges his signature taste for the bleak. The sad tackiness of Niagara Falls with its crappy motel architecture lies as heavily on the heart in these pictures as a lead x-ray blanket. Used cars and grubby scraps of snow stand in motel parking lots under flat gray skies. Lost, struggling souls, often ones that don’t look especially intelligent, are made picturesque in a way that only authentically downmarket people can look. [Ed. Note: The artist would not permit mnartists to use the images the writer wanted to run with this review until after the “debut” of his Niagara show this January at the Gagosian Gallery in New York.] Enlisted in Soth’s book, along with photos of his subjects’ wrenchingly sincere love letters, are quotes from Nabokov’s Lolita (Humbert and Lolita made a stop in Niagara) and Oscar Wilde’s comments on the pathos of the place, written long before an atmosphere even more depressing came to settle over the destination like motel room disinfectant. Soth persuaded a few honeymooning couples to pose nude in their rooms and for the most part the result is not a pretty sight… the photographs are made with a kind of solemn large-format documentary candor but they look like homemade porn. It’s hard to tell if they were made with a heart full of pity or one full of mockery. It would be easier to tell had Soth ventured a portrait of himself posed nude with his own wife in the same merciless light.

Tobechi Tobechukwu showed three different series of photographs, series so distinct from one another that they seem, on first tour of the gallery, almost the work of three different photographers. One of them is a group of nudes, but these nudes have none of the wry complicating irony of Soth’s pictures of people who are not so much nude as just stark naked. Tobechukwu’s are black and white prints of people confined alone or in groups of two or three inside a clear box made of Plexiglas—a projection of the idea of the glass ceiling into three dimensions. The crouched figures pushing against the hard transparency of the walls embody an extreme frustration with the oppressive racial, gender, and sexual prejudices that constrain social, economic, and ultimately, spiritual, mobility. The device works symbolically but is a contrivance that calls too much attention to itself, making the men or women posed within the box paradoxically more difficult to see (which may be the whole point). More powerful to me is Tobechukwu’s series of black and white inkjet-on canvas prints of women holding photographs up before their hearts of loved ones lost to violence… deeply serious portraits that remind me of the mothers, wives, and sisters who held up portraits of the disappeared in Argentina. Each one is like a knife to the heart—you know what they are without the labor of explanation. The photographs are titled with the women’s names: Regina Smith, Mary Johnson, T.L. Tolbert, Marsha Marshal… Tobechukwu’s third series, street photos in color from the Sudan, have the makings of a photo essay but lack the cohesion and conviction of the two series in black and white. In deciding to include them, the photographer blunts his sword, going in too many directions at once.

JoAnn Verburg’s uninflected portraits are the least assertive works in the show, quieter even than Beth Dow’s photos of gardens as botanical taxidermy. Verburg’s photographs are Minnesotan to a fault, protestant to the point of denying photography its powers of enchantment. In feeling and scale, they are next door to snapshots, mostly 5 x 7 prints, some framed in deep, funneling mats, some simply pinned to the wall, an inconsistency of presentation that says I’m not sure what. There is a reticence to these pictures that situates them on the other side of the moon from Soth’s brazen head-on encounters with people he doesn’t know. In many of her pictures, Verburg positions her subjects (most are women) in the frame as though half in apology for having inserted them at all. A few break the artist’s constraint and come at you–you feel like you’re looking into them, that Verburg’s vision has penetrated appearances and made you feel suddenly and strongly who they are. Many of the images, though, are not terribly revealing. Resolutely unseductive and rigorously anti-glamorous–plain photos of plain people, shot in flat light, their scale, shallow depth of focus, and fuss with the subjects’ position with respect to the horizon and features in the background seem a little dry and academic, congested by the photographer’s anxiety not to intrude. The photographer records them but doesn’t let us see who they are. The portraits bear no names, the absence of words here not necessarily to the work’s advantage.

A friend going through the gallery observed that most of the work of each of this year’s McKnight Fellows in Photography is in some way staged—nearly every shot is set up, carefully and unhurriedly composed. The tradeoff is a certain lack of spontaneity… what’s lost in the process is the instinct’s unmediated response to a sudden glimpse of order. Spontaneity is hardly the only thing that makes a photo strong or memorable, or the only criterion by which to judge its value, but my friend has a point: in this show the risks and difficulty of the street photographer’s hunt for the decisive moment are damped down by a guarded deliberateness of method. The continual onrush of chaos is kept at bay. Everything is under control, but like the people imprisoned in Tobechukwu’s clear plastic box, life is pushing against the glass of these photographers’ lenses to get out (or to get in.) When it succeeds–as it does in a few photographs by each of these four artists–the sensation of release is unequivocal… no words and no technique stand in the way.