Review: HYSTERIA at Soo VAC

Jakki Spicer does not become hysterical in her fascinating description and analysis of another intriguing thematic group show from Soo VAC, provider of bright colors and dark ideas. Show runs through March 21 at 2640 Lyndale Ave. S.

Hysteria, in its clinical sense, refers to physical symptoms that have psychological origins; Freud claimed that hysterics “suffer from reminiscences.” What cannot be properly remembered and integrated into one’s psyche transmutes into a somatic symptom: an unexplained cough or paralysis or catatonia. The more common usage, of course, pertains to someone (and usually a feminized someone) who is emotionally out of control, wildly crying or screaming or, perhaps, throwing pots and pans. It is true that many of the pieces in SooVAC’s current show indicate a pathology of memory—whether through the uncanny depiction of the traces of childhood, or by way of the more or less dated office technologies of card catalogues and carbon copies. However, it seems that these artists are concerned much more with maintaining control than losing it. The show might more convincingly be titled “Obsessive Compulsion.” SooVAC’s curator’s statement characterizes Hysteria as “an exhibition about obsession, repetition and personal reality.”

And these themes are notably present. Karen Snouffer and Michelle Weinberg’s 148 Hot Water Bottles, for instance, hints at the anxiety that haunts repetition. They draw hot water bottles from various angles, in various media—simple computer paint programs, in pencil on the pages of The Robber Bride, ink on newspapers, turning an ordinary item of comfort into an unsettling compulsion. Edie Tsong accomplishes something similar through her three pieces composed entirely of short blue ballpoint pen strokes. Blue Wonderwoman (2002), Blue Li’l Kim (2002), and Blue Self-Portrait (2002) are examples of a monochromatic neo-pop art pointillism that is unafraid of the obsessive-compulsive impulse of that art form. They demonstrate at the level of pure technique (and media—the ballpoint pen is especially effective at leaving traces of the strokes of the artist’s hand) the obsessive drive of the artist, whose differentiation from the mentally unstable seems particularly blurry here, against the clean strokes of the artist’s pen.

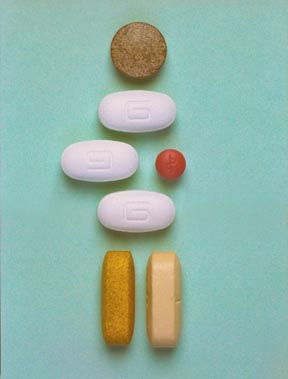

However, as Nicole C. Russell’s pill portraits demonstrate, it is not clear that any of us can declare an absolute difference from the slightly mad—indeed, our particular maladies become part of our individual identities. Portrait Series: Richard (2003), Kate (2003) and Self-Portrait (2003) are glossy, pharmaceutical-catalogue-perfect C-prints of each subject’s daily pill regimen: prescriptions, vitamins, painkillers. Is this a contemporary version of the old adage “you are what you eat”? Russel’s accompanying May Cause Dizziness is a handmade book identifying the depicted pills and others, accompanied by menacing descriptions of their possible side effects. Cause, effect, and side effect all make up our medicinal identities, but like obsessive compulsion, these works also display the perverse side of control: the careful monitoring of drug intake, like the careful repetition of pen strokes, enacts an impressive level of control that emerges precisely from the feeling of being frighteningly out of control.

Tucked away in the corner is another example of this relation, in Nori Pao’s The Random Behavior of a System. Halfway between art and a sci-fi bio-lab, Pao’s installation consists of several hanging pages of hand-drawn honeycomb grids of various sizes; in the center are Plexiglas boxes containing what look like science experiments in various stages of development. The color of glass and honey, the sticky, rubbery round shapes are both disturbing and beautiful. Again, this seems like an attempt to control the unknown, the uncontrollable, to chart and catalogue and systematize random behaviors. Trapped and displayed in their transparent boxes, the shapes inside seem to have a life of their own.

The office, like the lab, provides another metaphor for the anxiety of control, particularly over memory and circulation. Russel’s Inventory Incidents tranforms the archaic technology of card cataloguing into a daily journal. The small drawers, each labeled with a specific date, can be opened to reveal neatly typed cards logging daily events: “Sheets are stripped and washed,” “A plate falls on the floor,” “My presence is ignored.” Technologies the office has sloughed off the artist recycles in an attempt to individuate and remember her days. One wonders if the detritus of the daily grind breeds neurosis, merely provides the means to catalogue it, or provides some weapon of its own destruction.

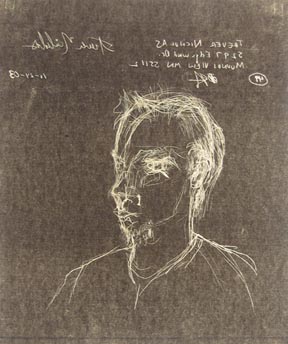

In another example, David Hamlow’s Friends Portrait Project (2002-ongoing) uses carbon copy invoices and black ballpoint ink as the media for a myriad portraits of friends and acquaintances. While the tradition of the portrait emerged from the budding Renaissance belief in the importance of the individual in his or her specificity, the canvas of invoices trades in the supposedly dehumanizing bureaucracy of business. The pages are treated as the receipt book forms that they are: each address section is completed with the subject’s name and address (almost all local, some of the faces you’ll surely recognize, including Suzy Greenberg, the founder of SooVAC), the date of its execution, and initialed by the artist as the “Salesperson.” However, the systematized procedures of business are not necessarily effective. Hamlow, after completing the sketches, would give the yellow copy to his subject and retain the white, consistent with office inventory practices. But when he decided to include the portraits in this exhibit, he had some trouble tracking down all the yellow copies; at the time of viewing there were still quite a number of blank spaces waiting for the carbon copies of their originals. Repetition and inventorying, even through mechanical reproduction, is no guarantee of maintaining control over circulation.

Theodore Kersten and Amy DiGennaro both employ the memory traces of childhood in their works. While Kersten uses bright colors, naïve style and visual puns to remind us of the world of children, DiGennaro produces intricate, (nearly) monochromatic and technically sophisticated images to bring us back to that world. Her Landscape with the Story of… (2003) is a giant map drawn in pencil, half of which is a meandering topography of curving lines, primordial icons and illegible place names, the other of neatly segregated and manicured lawns, sensible roads, and tidy houses. This juxtaposition is further complicated by the intricate border—much like those of fifteenth-century maps—peopled by fairytale characters, arrayed in a variety of Boschian activities, carried out in some discomfiting mix of pleasure and terror. Living somewhere in the dream world peopled by half-remembered childhood stories and events, these images evoke the uncontrollable confusion of memory, reality and fantasy that haunts our unconscious minds. DiGennaro’s Away (2003) and Our Recurring Nightmare (2003) echo this landscape, in forest and waterscapes, and bordered by extreme close-ups of ears and eyes. It may be that these pieces, even in their eerie quietude, best articulate what it is to experience the hysteria of “suffering from reminiscences.”