Reverse Engineering a Poem

Frank O'Hara famously asked, "What's the point of a poem if I have a phone?" Elizabeth Murphy reframes the question: What's a love song for if you can tweet? What's the value of "real" art spaces when there are online outlets like Artsy and Google Art?

“Poem” November 29, 1957

To be idiomatic in a vacuum,

It is a shining thing!

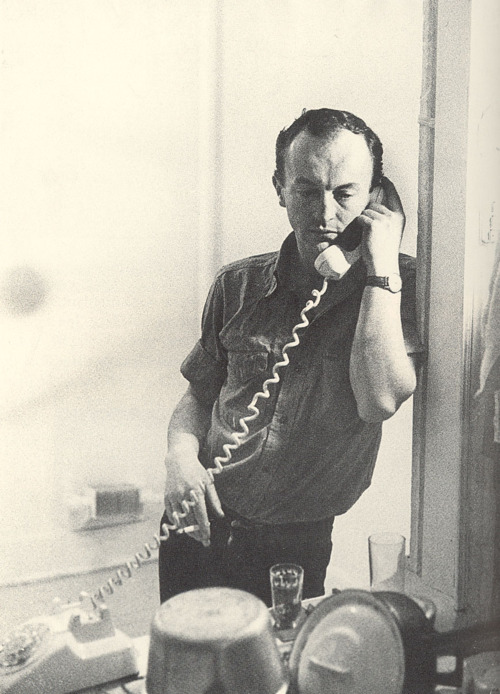

IN 1959, AFTER JUST FINISHING LUNCH WITH A FRIEND, Frank O’Hara sat down to write a love poem. The pursuit would hardly be worth noting — O’Hara was both a poet and in love — but our interest lies in the poem never coming to be. Specifically, as he leaned into the task of turning his thoughts to form, a sense of futility swelled in response: Why squander time fixing thoughts meant for one, when you can just call them on the phone?

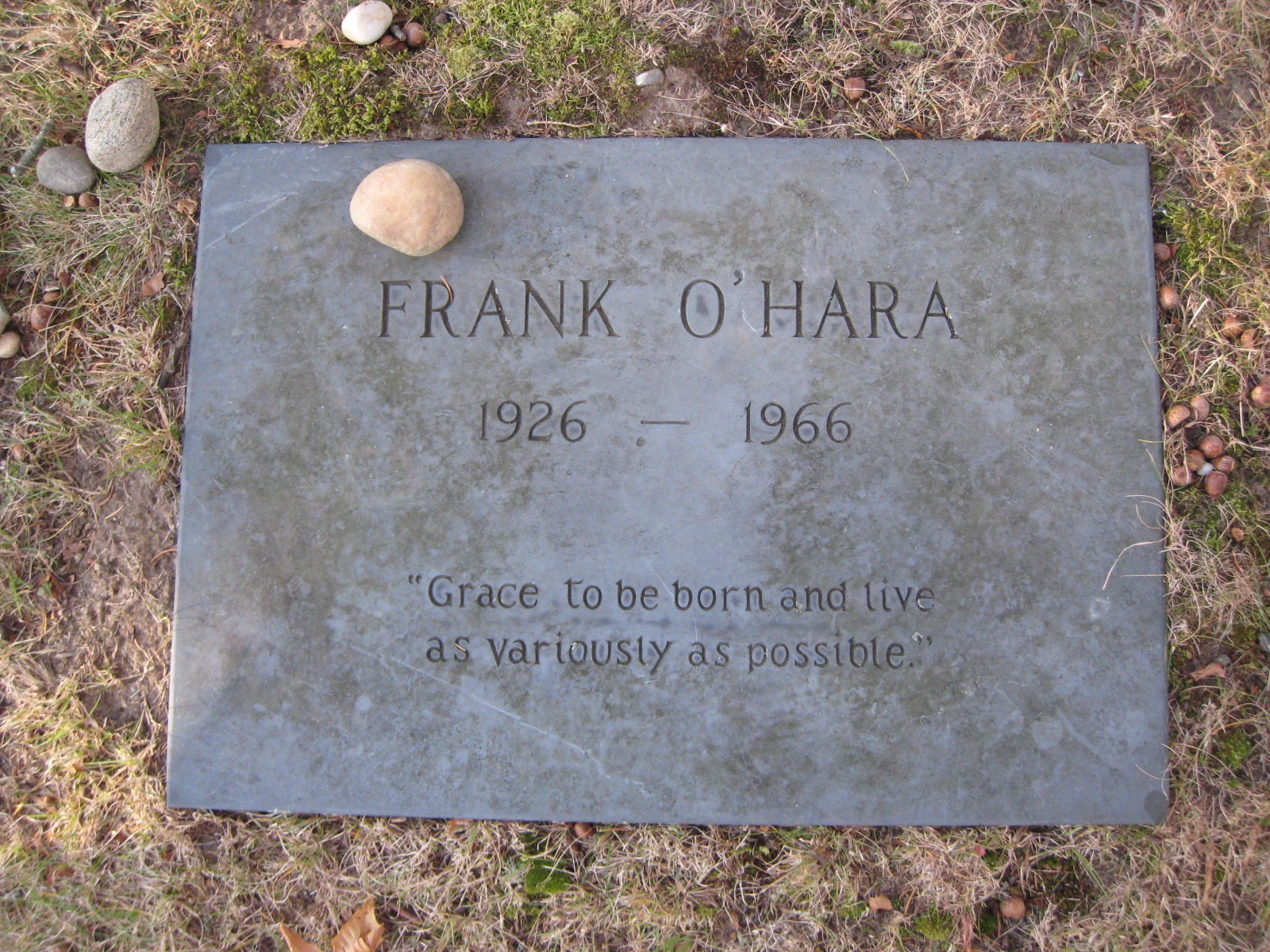

So goes the story of how Personism was born — a concept drafted by O’Hara in lieu of a poem one afternoon and later printed in Yugen Magazine, the publication of O’Hara’s lunch date that day, Leroi Jones (cum Amiri Baracka). He was a well-connected sort. O’Hara’s own writing confirms that both his peer circle and creative scope was capacious, including affiliation with the New York School of painting and poetry, a stint as a critic for ARTnews, and a career as a curator for the Museum of Modern Art. On the off chance you haven’t heard of Frank O’Hara before this, now that you’re aware of him, you’re sure to notice his name popping up often and everywhere. Dead at 40, O’Hara’s life was abbreviated with the kind of absurdity which feels too bluntly meaningless to print (but at risk of losing you to Wikipedia, he died in a freak accident – struck by a dune buggy on Fire Island). “Grace to be born and live as variously as possible” – so reads the inscription on his tombstone. He lived this credo, in part, through multidisciplinary immersion in the arts — and he was no a dilettante either. His was a mixture of giftedness and keen awareness to the delineations of medium: What suits what. Transposing a poem for a phone call, ‘Personism’ puts the poem “squarely between the poet and the person…the poem is correspondingly gratified … at last between two persons instead of two pages”.

The degree to which O’Hara’s tongue was in his cheek is debatable – ‘Personism’ is widely known as a mock manifesto, but summarily categorizing it as such does not do the notion justice, especially upon rereading in 2013. As Tony Hoagland laments in the recent Harper’s essay, “Twenty Little Poems That Could Save America,” poetry is largely absent from pop culture today. From the epic song culture of Ancient Greece to now, there’s neither coincidence nor surprise in the fact that the upward trajectory of mass communication runs right alongside poetry’s popular demise. But if we allow ourselves a bit of revisionist interpretation, there’s still fruitful hindsight left to mine.

Consider O’Hara’s timing: One can’t ignore the fact that when he asked that fundamental question — What is the point of a poem if I have the phone? – the technology in question was just beginning to become commonplace. Prior to World War II, telephones primarily served as business tools or novelties for the upper class; it wasn’t until after the war that they became a fixture in middle-class American homes. He seized a timely moment: A poet calling into question the merits of his medium, in light of a new technology positioned to upend the communicative purposefulness of poems. And as communication is still the motive at the core of artistic production, his query is more relevant than ever given the ever-more-rapid onslaught of innovations in media technology. Whatever degree of back-handedness or irony we may ascribe to O’Hara’s original thesis does not change the fact that, in 2013, the artist is faced with innumerable such intersections of old and new media which might prompt a moment’s pause for that artist, like O’Hara, to consider the continued relevance of her work.

For instance, what’s a love song for when you have social media? The internet has been quick to offer the music industry the benefit of its technology, and with it access to far-flung audiences artists couldn’t have dreamed of reaching before — by way of Napster, file-sharing, MySpace, Spotify, whathaveyou. These offerings may have proven themselves to be gifts of the Trojan horse variety, at least for the music business as we knew it, but I don’t think suspicion alone explains why so many individual artists have been slow to appropriate these technologies. Look at the content of the music, the lyrics, and there’s no evidence of them there either. Songwriting today has yet to cite, in earnest, the role that social media plays in contemporary courtship, for example. Think of that, especially in light of just how completely these networked communication platforms have commandeered how we form and sustain, or don’t, our romantic relationships in the last decade.

_____________________________________________________

On Facebook, anyone can be a curator and a critic. Anyone with a smartphone and Instagram is a photographer with global reach, or an Edward Muybridge on Vine, or a DJ – and they’re delivering it all instantly and without middle-men to the big Other, the internet.

_____________________________________________________

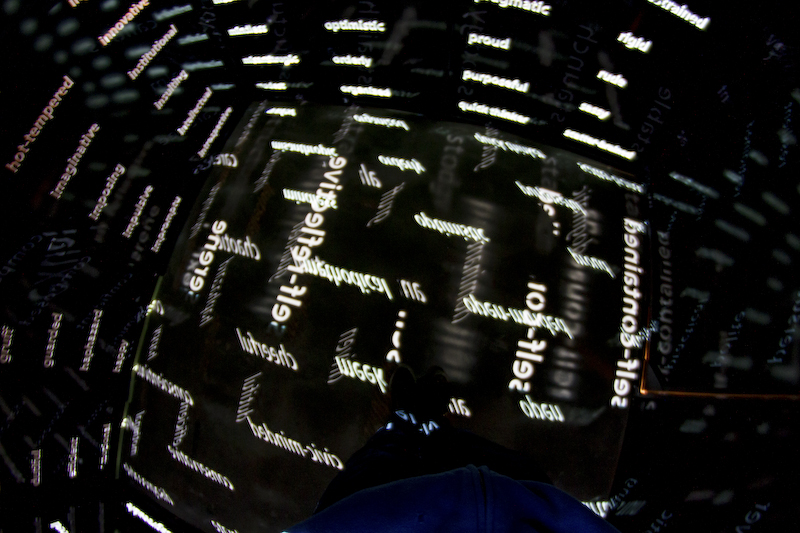

We could also ask: What is the value of real, physical art space in contemporary American cultural life, when there are online outlets like Artsy and Google Art? These online spaces make staggering amounts of visual material available to anyone anywhere but, advertently or otherwise, they also flatten the experience of seeing artworks — even an Ed Rushca is just one more image in a sea of images, another screengrab to copy and paste. And what about real, physical art museums in America? The large majority of them have been financially treading water, angling for deep-pocketed patronage to ensure their survival since – well, since their beginnings. These museums’ only hope at this point lies in adopting the very strategies employed by the virtual platforms which are at risk of supplanting them. No longer is it enough simply to present objects for display and invite the public to see them; museums now promise programming with interactivity, crowd-sourcing, immersion and “engagement” – all in the service of continued relevance.

Even as I write this, I wonder: Why do I feel the need to qualify that I’m talking about “real” or “physical” space in my efforts to invoke for you the concept of an art museum? These web-based technologies have become ubiquitous in our daily dealings such that the argot has co-opted our language of the literal. I mean, an “Analog Tweet”? That’s a postcard. The interplay between technology (new and obsolete) and language has always been the domain of the straight metaphor: Our brains were “hard-wired” circa Y2K, and yet we can still “read one another like a book.” And consider the impact still-developing mobile platforms might have; these technologies’ very invention undermines up-to-now universal narrative devices. For example, in a movie set in current-day America, the storyteller can no longer rely on the romance, or plausibility, of characters that are truly incommunicado.

In the first sentence of Personism, O’Hara declares himself “at the risk of sounding like the poor wealthy man’s Allen Ginsberg.” This scrappy authenticity – self-deprecating, yet audacious by the very fact of the comparison — tempered with a flair for nonsense and nonchalance, never fails for O’Hara. His public discourse through arts writing was unabashedly promotional of his peers: He extensively applauded the merits of Jackson Pollack, other friends and contemporaries who were bound, as he was, to the ideals of the “new American avant-garde.” But O’Hara also espoused the antics and rivalries of boxers and other pop culture celebrities. He’s like Norman Mailer’s abstract double.

Take the story behind Poem (Lana Turner has Collapsed!): It was prepared for a reading with Robert Lowell, an event O’Hara saw as “something of a grudge match.” And yet, high stakes or not, O’Hara didn’t actually start to write the thing until he was on a train heading up to Stanton Island for the reading. This is precisely the attitude that left an impression of carelessness, a sense that he did not really care seriously for his legacy, the fate of his poems. And in fact, once written, he often cast his pieces off – to be found in drawers, the laundry, the pockets of friends. I suspect O’Hara’s lack of attachment to the work didn’t signify disregard, but rather that once written the poem’s value was, for him, already spent. It’s in the writing that he had found the works’ worth, the crucial what’s what he was looking for in them.

Anything created expressly as art risks misinterpretation by its intended audience, and those risks are particularly pronounced with regard to poetry — by its very nature an oblique form. Personism, in its person-to-person immediacy, promises a solution: a message pitched and apprehended perfectly. Artists today pitch their work into a vacuum, their message less at risk of misinterpretation than insignificance, a victim of the anonymity that is the hallmark of these new media. The internet has everything, so it may as well have nothing. The glut ensures a terrifying weightlessness of information. Yet, “To be idiomatic in a vacuum/ It is a shining thing!”

Philosopher Slavoj Zizek argues that there’s a 21st century romance in this mode of communication where letters unfailingly reach their destination, and messages in a bottle are always retrieved. The rub is, the immediate adoption of one’s missive, while certain, isn’t guaranteed for receipt by a predetermined individual but rather a symbolic proxy — a recipient at once personal and universal “which receives it the moment the letter is put into circulation, that is the moment the sender ‘externalizes’ his message, delivers it to the symbolic Order, the moment the Other takes cognizance of the letter and thus relieves the sender of responsibility for it.”

_____________________________________________________

Museums’ only hope at this point lies in adopting the very strategies employed by the virtual platforms which are at risk of supplanting them — programming that emphasizes interactivity, crowd-sourcing, immersion and “engagement” in the service of continued relevance.

_____________________________________________________

The immediacy of this paradigm allows the artist to sidestep the critic. I can’t help but think of “Neo-Verity,” the genre recently coined by Jerry Saltz to qualify his choice for the number one work of art of 2012. If you missed his pronouncement, I guarantee you did not miss the performance that inspired it: dubbed by New York Magazine, “Clint and the Chair.” As an admitted subscriber to “institutionalism,” where art is identified by artists and art scholars pointing at things (“That’s art…this is art…THAT is art, etc.”), I found Saltz’s designation quite, well, pointed. He writes:

Robert Rauschenberg famously said that he wanted to work in the ‘gap between art and life’. Eastwood marks the disappearance of that gap. Life became art, fictionalized truth and made-up narrative transmuted into form. As with real art, time expanded, slowed down; viewers became aware of complex interplays between realities; logic was bypassed, multiple patterns of meaning formed. Unlike art, however, this live performance genre lacks the flexibility gene. It is unable to sustain any reading of itself except the one intended; it cannot tolerate paradox. This, oddly, is one reason it can exist in real time, (Also interesting: It’s critic-proof. No commentary can keep up.)

O’Hara’s manifesto presaged the disappearance of the gap Saltz speaks of. Art-theoretically speaking, we are only now catching up with that original Personist ideal – technologies’ persistent encroachment into art demands it. And few boundaries restrict participation: On Facebook, anyone can be a curator and a critic; anyone with a smartphone and Instagram is a photographer with global reach, or an Edward Muybridge on Vine; and obviously everyone is, and has been for a long time, a DJ. And they can deliver it all, instantly and without middle-men, to the big Other, the internet.

This sort of democratization isn’t new to poetry; the form has always been accessible to the amateur. All that’s required is thought, paper, pen. Or even brain, thought – after all, a poem doesn’t have to be fixed to exist. Bad or good, public or private, printed or fleeting: a poem — whatever its source or mode of dissemination – is recognized to be a bona fide poem.

Personism ignites a conversation about the assumed hierarchies of the form. We’ve tended to agree that if a text is published, it has value. But what of poetry? Once published, poems are the most easily reproduced of the reproducible arts. In copyright law theory, reproducible arts are considered a public good. That is because, like a lighthouse, they are nonexcludable and nonrivalrous: once built there is no stopping anyone from benefitting from their construction. It is hard to track this usage. The same goes for poems. Once printed, they can be copied by hand, memorized, photocopied, or copied and pasted.

But not a Personist poem: between two persons, excludable and rivalrous, a Personist poem is impossible to reverse-engineer or duplicate. And that’s invaluable.

_____________________________________________________

About the author: Elizabeth Murphy is a writer, art historian and musician. She lives in Memphis, Tennessee. Find more on her blog, Live At the Difference.