For All Your Life

A pair of writings—aural and textual, both mercurial—from a choreographic process considering the value of objects and lives

I am currently in the place of making. Where it’s happening is the form itself, at least for now. The past becomes the present becomes the future sort of thing. As I type these words they are coming from my mind to my fingers before I can really craft them. This is the action. Of constantly keeping up with my brain. Like tripping and recovering recovering recovering until that is my gait anew. It’s nice to be in a freefall of time, a rare luxury afforded by “process.” In the end, this will all transform into a live performance in New York. For now, I am writing. Thinking about only the thing that it is, instead of everything else.

Either, or

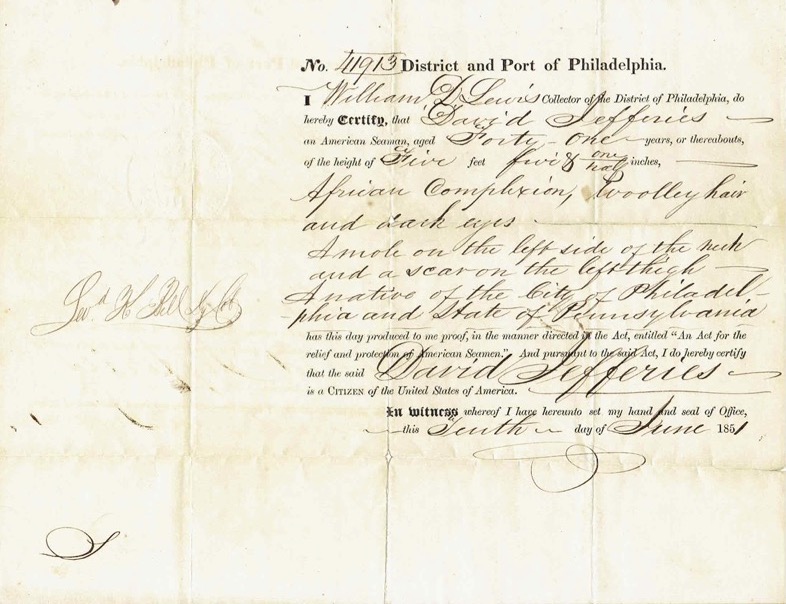

demarcating david jeffries

These are my ancestor’s free papers that certified he wasn’t a slave so he would move port to port as a citizen and American seaman. Something swells in me to see the passage of time through objects. A swell whose definition is still finding its way to me. Relics that tether me to specific moments of living, be it person, place, or thing. Something about old architecture abutting a modern design. Something about faded graffiti behind the remains of layers of wheatpaste. Something about old script and the Courier font of a typewriter on browned paper. What shores did he see? What ran through his head when he looked out at churning waves? How I hold this paper in my hand and this is what remains. A fraction of details from his time reflected in the facets of mine. But at least, there is this and it is something to keep. I stare at it for details I might have missed. It’s ruin, being the foreshadow of my life’s ruins in the making.

The precarity of a life at sea as a free black man is a cluster of dualities. As they traveled and worked they saw free black people in one port, while being recruited for the war in another, and did what they could to send messages and people across the diaspora. Life was between ports, air and water, family and shipmates, free to move about a ship bound to its waters. I forgot how I learned that the idea of insurance has one of its origins in merchant ships of the 17th century. To ensure vessels were well-staffed and their goods are taken care of, rich investors would fund voyages with the promise of some benefit upon the ship’s return, be that goods, gifts, or other profits from the trip. With the creation of a life expectancy chart, life insurance also became a thing. Sailors would go off to sea often months at a time and for those who didn’t return, local establishments would collect contributions from the community for families suffering from the loss of a loved one. Goods and life both had value and were commodified in such a way where both became worthy of being insured in case of loss. Slaves, being both property and lives, were in turn also worthy of such insurance. The giant New York Life Insurance Company was once the Nautilus Mutual Insurance Company and sold over 400 policies to slaveholders to insure their negro human cargo. Congruently, my great-grandfather became president of the black-owned Metropolitan Mutual Assurance company in Chicago’s South Side that provided policies for folks other companies would not insure. This neighborhood and family connection gave both my mom and dad, before they resembled anything close to parents, a stable summer job so they could gain upstanding job experience. It is also worth noting that I have a retirement account with the New York Life company my grandfather took out for me when I was a child. This duality of my existence—being supported by the notion of death and life being insured; while dealing with the ancestral trauma of devaluing black human life as property—fuels my obsession with the past and its objects.

I am not an artist from Minnesota. Although I have visited, exactly twice. Once, over a decade ago for a wedding. And second, to perform at the Walker Art Center in Will Rawls and Claudia Rankine’s What Remains in 2019. Throughout my career, I’ve performed in the street, in basements and rooftops, at 5:30 am, for an audience of seven, and now I can say at the Walker, too. Dance and performance at the Walker is not new. The black walls backstage are almost covered completely with white-markered scribbles that ripple out in every direction. Years and years of artist’s signatures, familiar and legendary, a collection of the ghosts of our performances, color the walls behind the theater a bespeckled grey. Every name there once had a first time performing at the Walker, like me. And I wonder if they too spent quiet moments, mouth agape, reading the walls foot by foot in search of the names we know. I’ve felt this feeling exactly once before on another legendary backstage wall. Of the many devastating reasons the fire that leveled the Ted Shawn Theater at Jacob’s Pillow, was the loss of that register and the span of the history it held. But we’re already ghosts of yesterday, by being today’s days old.

I used to practice my signature in notebooks when I was a kid. I still have my diary from when I was ten. The practice of my perfect signature wasn’t so much preparing for a fantasy life as a movie star or Madonna, when I would need to execute my signature with the ease and grace of someone who has done it a hundred times. No, I wanted to fill the page with my name, and take up space. I wanted consistency. And I wanted a design that was totally my own. Something to bounce about in echoes on the walls of my tomb. Doesn’t every diary hold such a page? That, and our fragmented dreams, fantasies, and proclamations of beginning anew? This habit, for me, is born from the greatest fear a person can have: being forgotten. Or legacy. Or whatever.

When I hold an object like these papers, its reality destroys all the fantasies I’ve created to just summon the courage to look at it. Its failure in detail is futile, like trying to leave a mark in the middle of the ocean. “African complexion.” “Wooly hair.” “And dark eyes.” Such little description remains of a whole life. His existence was chopped up in pieces and tucked in kerchiefs behind the loose brick in walls all up and down the east coast. And it’s my treasure to seek. I dream that David Jeffries was an adventurer, an ideas man, a poet, who felt swells in his chest, unnamed like mine. Who felt time stop the way it does in the middle of the ocean. Whose sea drifting preceded all my memories, real or imagined, of the past. Sometimes as I’m writing, I’m imagining someone finding my words later, after my death. I try not to edit as I go, in order to bring authenticity to any practice I do. Still. I write as though I’m being remembered. To know the details is to name them, fantasy and all. And to name them is to contain them, and then we set course for a story to remember. Its own objectivity, in waiting.

Audio transcript available on page 2.