Restless with a Hunger to See: The McKnight Photo Fellows

Glenn Gordon saw the McKnight Photography Exhibition at the Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota and was impressed: this is a great show. It's a fine way for the Nash to wrap up its stewardship of the program; next year it moves to the MCP.

The 2005/2006 McKnight Fellows in Photography exhibition, a show you should not miss, is currently at the University of Minnesota’s Katherine E. Nash Gallery and will run through October 5. The four McKnight photographers this year are Meg Ojala, Natasha D’Schommer, Todd Deutsch, and Richard Copley, and for the most part they have put their backs into it, setting works before our eyes worth lingering over, and, once they’ve sunk in, worth visiting again.

Meg Ojala’s large square color prints frame close views of the tangled and disheveled underbrush of the woods and fields near where she lives—images of dry bent stalks of grass, the few last leaves clinging to twigs, snow on the ground in March. Found, calligraphic compositions photographed in a manner mercifully free of cliché, the images are taken using very shallow planes of focus, the sharpest segments of the pictures most often off-center or unexpectedly off to one corner. Only a few beautifully discerned details are sharp, the rest blurred, as though trembling or perhaps stirring slightly in the wind. Hand-held, the camera might have trembled slightly too.

The images are shot with the candor of a heart open to things as they are, and correspond to the way we actually see, the object of the moment’s attention in focus, everything else always slightly out of it. “Prairie Snow in March, #3,” calligraphically the simplest of these images, has a triad of thin stalks of dry grass in sharpest focus, curved like the tines of a fork, with two other stalks standing stiff and vertical on the left side of the frame. Most of Ojala’s pictures, however, are more complex, the underbrush denser, you have to peer harder to see into them. In the foreground of the picture “Twining. Late April,” the creeper of a grapevine coils around a stalk dividing the picture vertically almost down the middle. The foreground is shot in shadow and has just a few leaves and bits of coiled creeper in focus. The blurred foliage of the underbrush in the background beyond is in sunlight. In “Near Wolf Creek. Late April,” a composition of thin dry stalks stands against an indeterminate background of the palest yellows. One straight stalk is bent sharply to form the two straight lines of an acute angle, its severe geometry set off and softened by slightly blurred curved leaves of the same grass, The element in sharpest focus, for all that, is a curved branch with delicate little kayak-shaped leaves, off to the lower right. “Wolf Creek Dogwood. Late April #2,” a composition that might be embroidered on Chinese silk, has as its focal point one specific single little russet flame of a leaf budding on a horizontal twig, the bud of another leaf right behind it out of focus and uncurling in the opposite direction.

“Last Light Near Trempeleau,” a picture whose title is a short story in itself, is a large print of branches with decaying leaves shot against a dying grey light. A few of the leaves are in focus, but some, closer to the camera’s lens, are not–they abstract into beautiful blots of pure russet.

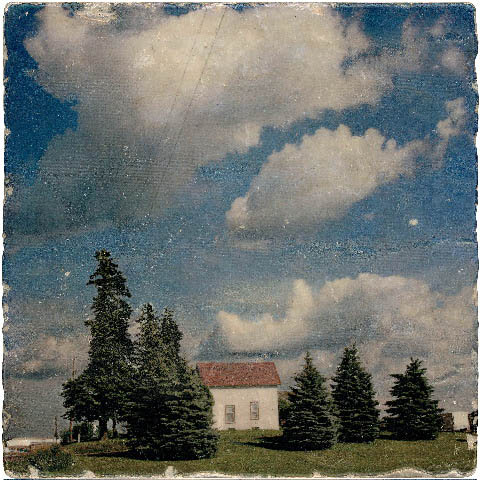

Photography being a matter of trapping moments which evaporate the instant they are born– the very stuff of evanescence—there is something paradoxical about the sight of photographs set in stone, a paradox the photographer Natasha D’Schommer explores by transferring her images to the surfaces of lithography stones. The imprinted square flat stones are themselves then photographed, and in the end presented in the form of framed giclee prints on fine deckle-edged watercolor paper. By this time, several generations along from the image first snapped by her shutter, D’Schommer’s process has transformed the image, worn it down, aged it, given it signs of wear. The chipped, irregular edges of the stones show all around like the ragged edges of the paper they’re printed on, and the images themselves are pocked and scratched, with bits missing where the face of the stone was pitted.

The images, all in color, are mostly of rural and suburban landscapes, with horizons low and the skies above them big. Mixed in with these are some full-sized images of embroidery and old dishtowels, their colors faded after years in the kitchen. The color in some of the images is like that of vintage hand-colored postcards. Some of the landscape and farmstead images look not like photographs but like neglected old watercolors or tinted etchings. The process stiffens the subjects into images that appear not merely frozen but preserved in a kind of visual canning jar. It seems to throw the impulse to photograph into reverse, back towards the painted image. D’Schommer’s images are interesting less for their content than as an exploration of another one of those things you can do with photography, images now being transferable to everything, from whole buses to t-shirts, mouse pads and mugs, with the difference that this photographer’s images look as if unearthed at an estate sale fifty years after the fact.

The work of the two other McKnight fellows, Todd Deutsch and Richard Copley, are deployed around the gallery in such a way that segments of one artist’s work leapfrog and to some extent interrupt the flow of the other’s. The discontinuity of the presentation is disconcerting, but you can still tell whose works are whose: Copley’s photographs are black and white, presented in black frames, and Deutsch’s are all color, in white frames.

Todd Deutsch, peeling back the curtain (a curtain in some cases made of black plastic garbage bags) on the grubby world of full-immersion video gamers, shows a collection of powerful images shot during marathon LAN [local area network] sessions where gamers converge in the featureless meeting rooms of hotels and convention centers for long Walpurgis Nights of virtual annihilation. Some gamers are crashed out in sleeping bags next to tables arrayed with monitors whose thick dreadlocks of cables are crudely duct-taped to floors strewn with debris, empties of Mountain Dew and Monster, crumpled bags of Munchies, and boxes of Cheez-its. Others, jacked up on caffeine, their faces bathed in the sickly glow of CRT’s and LCD’s, sit slouched in concentration, their eyes glazed, the joysticks in their hands like prosthetics for learning to feel.

The rats’ nests of cables and wires are, like Meg Ojala’s underbrush, hard to make order out of, but Deutsch finds it, and even a kind of imbecile rapture in the gamers’ faces. In one portrait, “Lok 1,” a lanky dude in a phone headset and a skewed baseball cap sporting a death-metal cross sits with the game controller held loose in his hands as if it were a divining rod. In another, “Assphault Assassin,” we face a guy, visible behind his bank of monitors only from the eyes up, staring into the screens from underneath the bill of a Budweiser cap with a flame job. The portraits of three solitary gamers, “Speck,” “Killerfoo,” and “Pates,” are hung together to form a triptych of sorts, a trio of geek saints in the throes of divine transport. Picking up where Carravaggio left off, Deutsch’s amazing “Halo 2” speaks of a Dark Age to come: two gamers, receded into the shadows of their hoodies, sit like monks in the crepuscular dark, their faces barely touched by the dim wash of the light from a large-screen TV.

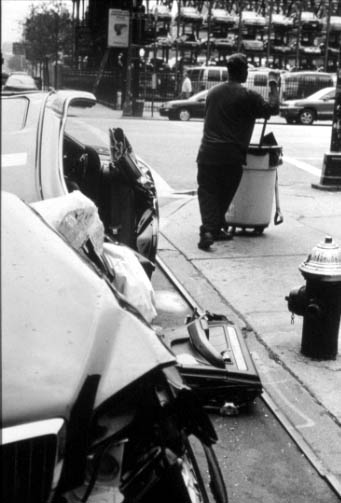

For the fourth exhibitor, Richard Copley, a seasoned street photographer, the game is different. Grand Theft Auto in your dorm room is one thing; the actual streets of New York are another, and the game there is trickier. For Copley, the lever on the non-stop slot machine of the action on those streets is the shutter button of his Nikon, every release of that shutter a shot in the hunt for the elusive moment when, for just an instant, the world falls suddenly into place and things come up three cherries in a row. A hunter of epiphanies, his only prey experience itself, Copley has been shadowing street life for more than thirty years. Like many great street photographers, he works in black and white, it being more succinct.

Some of the works are rim shots—one-liners, but bullseyes—nailed, like certain moments of jazz. The picture, “East Village. Cocked Hat,” is made to sing through the insouciant curl of the brim of a fedora, a tiny detail, like a stroke of musical notation. Another story told in the space of a single moment is “Howard Johnson’s. 46th and Broadway,” showing a busboy lying asleep in the booth of an empty restaurant while people like those he waited on at lunch stream past the window outside. Far more complicated is “West Village,” a picture of such crazy complexity it takes a minute to sort it out. The gesticulating hands of half-a-dozen New York lunchtime pedestrians fill the foreground, the background, and everyplace in between, one holding a sandwich, another making a point, the hands of the two guys conversing in the middle distance working overtime. In “9th Ave. and 35th St.,” all is vanity: In the background are neat stacks of cars in a parking structure. In the foreground, crumpled against the curb, is the wreckage of a car that’s been totaled. In the middle distance between them, a street cleaner waltzes a garbage barrel along like a dance partner. In “Under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Brooklyn,” a portly old Orthodox Jew stands alone on the empty street below the soaring curve of the expressway inquisitively poking his cane at a curious pile of discarded old clothes, reminding me, for some reason, of Rembrandt’s Aristotle, contemplating the bust of Homer.

One last favorite, a photograph of great majesty, is “10th Ave. Highline,” a picture as mysterious as a work by de Chirico. The shadows of two figures are cast on the wall underneath an elevated railway structure but you can’t see the people themselves. They are blocked by a riveted column supporting the el. Against that column, partially visible from behind, leans a man, but you can’t see his head—he is equally anonymous. The shadow cast on the sidewalk by the curved support of a street sign exactly echoes the arched entry to a building further down the street. The geometry of this picture is amazing. Working with a simple camera and the courage and wit to risk spontaneity, Copley, like a musician playing live, understands the irreproducible singularity of every moment of existence—every one of them a birth and funeral at the same time.