Reexamining the Rules: Tom Rose

Mason Riddle here writes a thoughtful essay on Tom Rose's work, exemplified by his recent show at Flanders Gallery, "Rules of the Game."

Like the next essay in an anthology of creative non-fiction writings, Rules of the Game is Tom Rose’s most recent investigation into such familiar but innate abstractions as knowledge, memory and sense of place. This exhibition of twelve mixed-media wall reliefs and large-scale, black and white inkjet prints mounted on canvas is a personal discursive effort to give visual form to the intangible ways in which we are shaped by our educational experience – not only through the information imparted, but also through daily socialization that is to mold us into full-fledged, accountable human beings. For Rose, the educational process slowly constricts our behavior in order that we abide by accepted social norms. Boundaries are established and we learn how to play by the rules of the game and, hopefully, learn about the larger world.

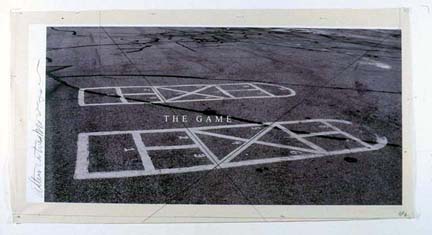

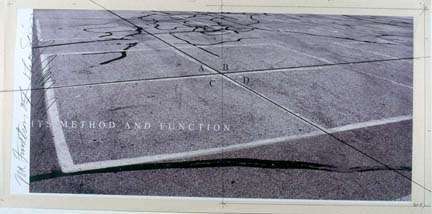

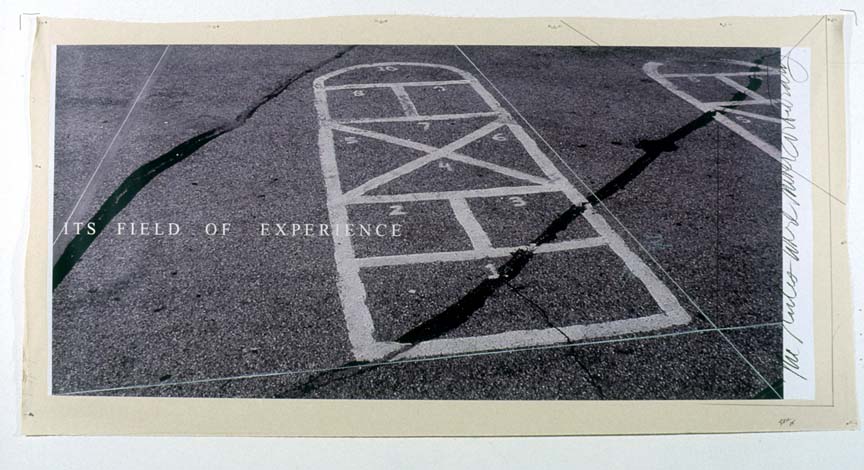

Rose’s tactile works are elegant, tightly composed amalgams of photographic images, text, drawings, tools, objects, furniture and materials all reminiscent of the educational process. The works are not literal but metaphorical: through image and material, an iconic, experiential notion of “education” is constructed. Photographs of chalk-marked asphalt playgrounds or rows of metal coat hooks, pieces of slate inscribed with gestural images and words that recall blackboards of spelling and arithmetic lessons, panes of etched or sandblasted glass that test our ability to see and remember, and actual objects such as a C clamp, black wool yardage, a book and chair, collectively create oblique but associative narratives. And, individually, each work seems to symbolize a visual signpost that marks the path of personal growth.

For example, in the photograph titled The Rules Were Never Arbitrary, a numbered hopscotch game on asphalt is overlaid with the phrase, “Its Field Of Experience.” The work suggests that the participant must consider whether playing by the rules is superior to actual experience, and if the two cross-pollinate to create behavioral norms. In the wall relief titled Method, a black and white image of Rose’s Romanesque-style brick elementary school in Milwaukee, the Albert E. Kagel school, is layered with a sheet of etched glass, a carpenter’s square and a piece of slate on which a geometric form is drawn in perspective. Floating before the school’s facade is the word “method” which raises multiple issues: the idea of instruction, the skill to count and measure, the importance of understanding form, and the ability to see clearly.

These are complicated works whose spare but seductive materials, combined with photographic images documenting fragments of school life, offer a compelling perspective on the educational process – learning – from child to adult. Although not didactic works, they inform by their power to conjure up memories and often forgotten experiences. Austere, calculated, and architectural in their construction, these works formally address the picture plane – its ability to be both opaque and transparent, to be a support for both abstract gestures and ideas and representational objects, all issues of importance for Rose for 30 years. Those works which are most simplified in their construction and use of materials are the strongest for they allow for a clearer, less cluttered investigation of the ideas and associations at hand. Collectively, they seem to identify how complex human life becomes out of the most ordinary experiences: going to school, learning to read, and playing.

Since the mid- 1990’s, Rose has been working on an expansive project, of which Rules of the Game is the most recent installment, that comprises many forms and explores not only the impact of one’s educational process, but also considerations of place, and how the two form one’s identity. The project’s first incarnation was collectively titled The School Stories. As part of this, in 2002, Rose created a mixed-media installation for the Nash Gallery at the University of of Minnesota titled A is for Artist: The Art of Forgetfulness, a spare, associative evocation of grammar school. This coincided with an informal symposium at the Weisman Art Museum, titled The School Stories: Conversations on Rhetoric and Memory, whose participants included the acclaimed critic Arthur Danto. For The School Stories, Rose contacted a number of men age 40-86 to pen narratives about their educational experience, which ranged from unremarkable to poor, yet they managed to move on to “become something.” In 2003, these memoirs became part of a limited edition, artist-made book printed and bound by Minneapolis’ Indulgence Press, and titled Where Do We Start? Its square format and crimson binding contain pages that unfold which are marked by passages of text, drawings, and photographic images, and two CDs burned with the men’s memoirs. In 2005, Rose mounted a related exhibition and created a second hand-made book with an essay by Danto. Titled 1018 W. Scott St., both book and exhibition focused on Rose’s ivy-covered childhood Milwaukee home that was built by his architect grandfather, Thomas Leslie Rose, whose firm also designed and built Minneapolis’ Orpheum Theatre.

In the end, there is something satisfying, if not significant, about an artist’s body of work which takes many forms yet manages to investigate a single idea or set of ideas over time, from various depths and perspectives. Rose has done this expertly, with a sharp intelligence that is both personal and universal in its reach.