Really Seeing for the First Time

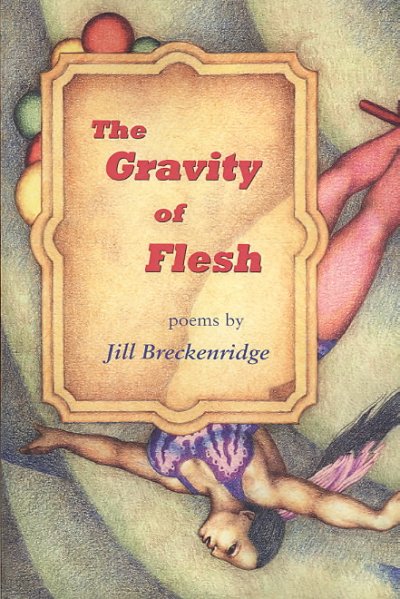

Connie Wanek offers a close reading of acclaimed poet Jill Breckenridge's latest collection, "The Gravity of Flesh," and finds the eclectic assortment of poems -- ranging from pithy haiku to longer-form prosaic pieces -- insightful and deeply engaging.

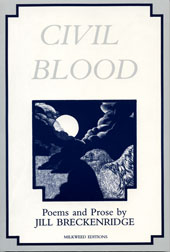

JILL BRECKENRIDGE‘S CIVIL BLOOD, PUBLISHED IN 1986, CREATED QUITE A STIR. It was an important book regionally and nationally, a richly imagined, thoroughly researched evocation of the Civil War, through poems and prose, as experienced by General John Cabell Breckinridge and a cast of souls involved in that terrible conflict.

Nodin Press has just released her new collection of poetry, The Gravity of Flesh, and it was well worth the wait. It’s a much more intimate book, but like Civil Blood, the new collection has a strong narrative element, within individual poems and as a whole. It also reveals Breckenridge’s signature ability to observe the world and the people in it, intensely and “without prejudice,” as they say in the law. And this is much harder than it seems at first blush.

Her website’s “about the author” section tells us that she earned an MA in Counseling Psychology — that’s not surprising. Just as the effective psychologist must empathize with a patient and, at the same time, hold on to a measure of emotional detachment, so Breckenridge maintains enough distance from her subjects (even when that subject is herself) to be both a credible reporter and a poet of insight and transcendence.

The Gravity of Flesh is divided into five distinct sections, each with its own character. The first section is memoir-esque, with poems about a childhood in the Wild West; the second concerns motherhood and family life. The third section is comprised of poems about the Minnesota State Fair. A social conscience and illness enter the gritty fourth section, while the last contains poems of aging, of reconciliation and hope. That’s a lot to cover in one book! Breckenridge has a tough-mindedness that eliminates the non-essential, though, and it gives the book an exhilarating density. She never wastes the reader’s time — every poem matters.

The title of the book is also the title of the third section. The Gravity of Flesh suggests at least three things to me, besides the root word “grave”: first, flesh sagging with age; also the weight of a body, and what happens when it falls from a great height (the book cover shows the image of a woman hanging by her feet from a trapeze, and in the poem “Contour Line Drawing” reference is made to victims who held hands as they leapt from the burning towers on 9/11).

Finally, the title suggests that flesh itself has a kind of gravitational pull. Sexual attraction comes to mind. In the State Fair poem “The Bond of Flesh” a couple rise to their feet as they watch a death-defying performance by a motorcycle stunt man and the woman who “dangles under him,” her “arms outstretched toward her distant grave.” The moment — the spectacle — draws the couple closer, as he “rests his arm around his wife’s shoulders” and she “relaxes, laughing,/ as she leans on him.” He’s a mechanic, “10-40 oil/ still lines the fold and curve/ of his strong fingers” and she forgets “to hide her bad teeth.” Our shared humanity, our very flesh and its perishability, exerts a kind of gravitational pull that brings us closer.

These State Fair poems echo the themes of her earlier work, foremost among them the idea that stories must be told. “We live our lives with eyes half closed,” Breckenridge says; but she doesn’t. The tale of Pretty Ricky, a 1200 pound pig; the story of Marjorie Johnson, “bake-off queen”; the spectacle of Ronnie and Donnie Galyon, Siamese twins (“They are real, human, and alive,” says the ticket hawker) — all are compelling, fascinating. One might say these tales have a gravitational pull, or to use Breckenridge’s phrase from “Contour Line Drawing,” we are “really seeing for the first time.”

______________________________________________________

The tale of Pretty Ricky, a 1200 pound pig; the story of Marjorie Johnson, “bake-off queen”; the spectacle of Ronnie and Donnie Galyon, Siamese twins (“They are real, human, and alive,” says the ticket hawker) — all are compelling, fascinating.

______________________________________________________

I was struck early on and often by the formal variety in The Gravity of Flesh. Some poets settle into a pattern, consistently writing lines and poems of a certain length, and with other persistent similarities. Not so here. “Bamboo Tray Variations,” for example, is a collection of twelve haiku, one for each month of the year. By contrast, “Coming of Age in the Fifties” is a long, almost cinematic prose poem. “Midway” alternates between short and long lines. “Joined Flesh” creates a literary mirror on the page: just as the twins are bound to each other at the waist, so the poem’s lines proceed to the midpoint, then are repeated backwards. This formal inventiveness is hugely appealing. Charles Olson maintained that in projective (or open, or free) verse, “right form, in any given poem, is the only and exclusively possible extension of content…” A subject will find its form, if a poet is attentive.

The Gravity of Flesh contains forty poems, and thirty-three of them are my very favorite. Here, to illustrate what Breckenridge can do with metaphor, with detail, with one of those troublesome, philosophical “-tion” words as a title, is a poem in full:

Revelation

Three Mexican women, dark stars

of the Aerial Thrill Circus, rise

high above the crowd. Lifted up

by their heads and La Cucaracha,

they take off their teal-blue dresses,

stripping down to silver sequins,

bare legs, bare shoulders and backs,

as the crowd cheers on this near

revelation. Three dresses fall

slowly, silken feathers from beyond

where we can run or jump,

as the silver women, alone in the sky,

submit again to the universal spin, faster

and faster, their bodies blur

into motion and light, then slow

and descend again, epistles written

within their shining bodies

and delivered back to earth by these

devout children of the innocent air,

who will never tell us what

they have learned, except to say,

by example, that it can be done.

The layered meanings of these images — the women as messengers, possibly divine (“devout children of the innocent air”), delivering, not commandments, but courage-by-example — and the complexities of these lines give me exactly what I’m seeking when I read poetry. To bring to light every nuance in these lines is not really possible; or, if it is, such an undertaking would require hours and pages for the telling. Surely one’s time is better spent simply reading the poem. Breckenridge is an efficiency expert. Just the crucial words, no more.

The Gravity of Flesh answers Dana Gioia’s famous question, “Can Poetry Matter?”, sharply in the affirmative. Breckenridge’s poems reach out with humor, compassion, anger, charm, anguish, insight, hope, and love — never once losing the conviction that the world can be full of goodness, and fair.

______________________________________________________

Upcoming author readings by Jill Breckenridge:

- October 10 @ 3 pm, book-signing (at the Nodin Press table), Rain Taxi Book Festival, Minneapolis Community and Technical College

- October 20 @ 7:30 pm, University Club, St. Paul

- October 26 @ 7 pm, Barnes & Noble, Har Mar Mall, St. Paul

- November 4 @ 7 pm, Barnes & Noble, Galleria, Edina

- November 15 @ 5 pm, Magers and Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis

______________________________________________________

About the reviewer: Connie Wanek is the author of two books of poems, Bonfire and Hartley Field, with a third, On Speaking Terms, forthcoming early next year from Copper Canyon Press. She also co-edited To Sing Along the Way: Minnesota Women Poets from Pre-Territorial Days to the Present. She was a 2006 Witter Bynner Fellow of the Library of Congress.