Reach Out and Touch Something: interact/react at the Minnesota Museum

Glenn Gordon marvelled at the moving, vibrating, buzzing, humming realm of sculpture at the Minnesota Museum of American Art at 50 W. Kellogg in St. Paul, down the street from the Science Museum. Through May 29.

The first work you encounter on entering “interact/react,” the adventurous new show at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, is a horizontal tornado. It only kicks up when your presence — picked up by motion sensors — sets off a brief furious whirlwind of dry autumn leaves. The work, Eyes of the Wind, by the artist Diane Willow, is a turmoil created with leaf blowers contained by a structure of clear plastic film stretched over giant fiberglass hoops.

Ms. Willow’s Eyes of the Wind reacts to the sight of you by kicking up a storm, a storm that can only blow because you -– interacting with the piece — are there to set it off. The work perfectly embodies the premise of “interact / react.” Imaginatively curated by Theresa Downing, the show presents pieces by eleven artists whose work incorporates interactive or reactive elements, employing everything from the simple behavior of a single source of light to complex computer-generated projections to involve the viewer -– in most cases actively — in physical and psychological expressions of motion and action. Among the works are kinetic and mechanical sculpture, digital video projection, conceptual art, and installations.

The earliest works in the show are two kinetic sculptures of stainless steel done in 1967 by the late George Rickey. The delicate equilibrium of their pivoting plates is disrupted by the slightest touch or movement of the currents of air around them, putting them into gently bobbing motion.

The only other work in the show not to have been created fairly recently is Norman Anderson’s Wailing Wall, a Rube Goldberg music-making contraption commissioned for the MMAA in 1983 and now a part of the museum’s permanent collection. Essentially a calliope driven by electrical impulses instead of pressurized steam, you operate it by dancing upon a dozen floor tiles that are wired, when stepped on, to send signals to strike, twang, clang, and blow an array of drums, guitars, cymbals, bells, organ pipes, and whistles mounted neatly on the wall.

A couple of other artists in the show also take Rube Goldberg for their patron saint. One of them is Jeffrey Zachmann, whose tightly crafted Kinetic Sculpture #301 is a wall-mounted homage to pinball machines. Its steel marbles set off on a complicated adventure the moment a viewer presses a button to put things in motion. The other is the former rocket scientist Tim Fort, a master of the art of the engineered collapse. Fort painstakingly sets up what have come to be called “tumbles,” elaborate comic chain reactions. He will spend hours precisely arranging sequences of popsicle sticks, playing cards, balloons, parts of tinkertoys, bottles, funnels, plastic cups, and bits of string all so that they can, when triggered, fall like dominoes over a period of say, thirty seconds. He videotapes the tumbles, and they are just as funny on tape as they are in person.

The artists in “intereact/react” employ technologies that range from the utterly simple to the fiendishly complex. Bill Klaila’s Forest Rain is a computer-generated digital image-and-sound projection of a forest of wind-tossed trees in rain and mist. Depending on where you step on the digitally sensitized mats on the floor of the piece, you actuate the sound of leaves crunching underfoot or the squishing sound of your feet in puddles. Klaila’s reactive installation is totally contingent on software, but he regards what he’s doing as just a continuation of the American landscape tradition. More interactive, in the sense that the viewer’s hand chooses and controls how things play out, is Patrick Kelly’s mysterious leger instare, another video projection with sound, this one supplemented with large inkjet prints – still images from the video — mounted on the wall.

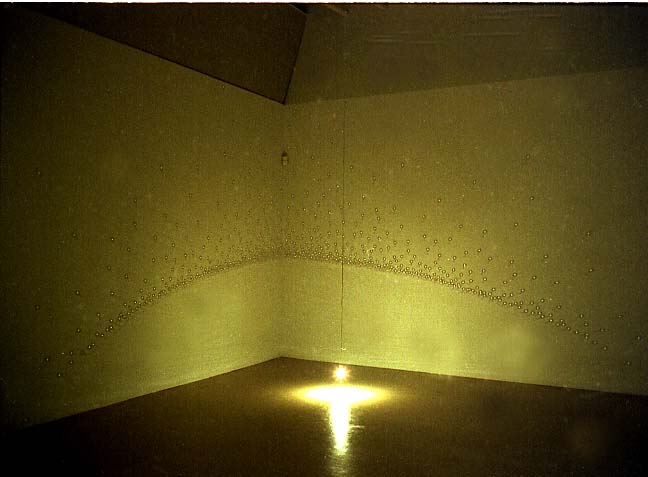

Far simpler, in a piece called Faces East (for Cid Corman), is Charles Matson Lume’s ingenious use of a single bare light bulb and a couple of hundred toy magnifying glasses of the kind you used to get in a box of Cracker Jacks. The bulb is suspended in the middle of the room from the ceiling by a cord holding it to within a foot of the floor. The viewer can make it sway back and forth like a pendulum. The magnifying glasses are glued — not flat, but by their edges -– into a wing shaped pattern on two white walls standing at right angles to each other. Swinging the light bulb, a point-source like the distant sun, causes the magnifying glasses to refract the bulb’s light in moving patterns on the walls, each refraction looking a little like the eye of an albino peacock feather.

Adjacent to Lume’s piece is a piece made of actual peacock feathers, supported by a wide ribbon of fine metal mesh projecting from the wall. The piece, by Diane Willow (creator of the show’s opening windstorm) is called Soft Touch and it is puzzling; it doesn’t seem in any way kinetic until you learn that, against all usual art museum etiquette, you’re invited to touch it. The mesh is fitted out with tiny micro motors that cause the peacock feathers to tremble, but only imperceptibly. You can’t tell until you touch them and feel them quivering rapidly as the heart of a small bird in your hand. You have to reach out to touch and interact with it, as the artists in this show have done with you.

See the links below to visit the homepages of artists in the show who have sites on mnartists.org.