Portraiture sans Politics: Eastman Johnsons portrayal of the Ojibwe

Julia Durst reviews Eastman Johnson: Paintings and Drawings of the Lake Superior Ojibwe at the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth. This rare look at a nineteenth-century artists take on the region is up through October 29.

Artists have motives. They have hidden messages, occasional agendas. For this reason portrayals of American Indians have varied throughout U.S. history, ranging from helpful teachers to untamed savages. Such renderings often supported whatever the government’s current social policy was.

But intentions were not always sinister. Sometimes art history offers up visions of clarity. Motives can be pure. Eastman Johnson’s seemed to have been. Johnson (1824-1906) painted with remarkably dignity and apparent objectivity the Ojibwe people he observed during a trip to the Lake Superior region in the mid 1800s. His collection of American Indian images stands as one of the few documents of Ojibwe life in nineteenth-century art.

A well-known artist in his day, Johnson spent most of his career painting sedate rural scenes and portraits of important people. He visited Superior, Wisconsin, from 1856 to1857 to visit his sister Sarah, her husband William Newton (a Superior pioneer), and Newton’s brother Reuben (a sawmill owner). During that time he observed the Ojibwe near Grand Portage and what is now Duluth-Superior.

Johnson’s current exhibition at the Tweed Museum includes portraiture and landscapes from his visit. From one drawing to the next, the restraint Johnson employs visually and conceptually resonates. With his economy of line and powerful, selective use of shadow, Johnson doesn’t overdo it. Nor does he idealize or editorialize his subjects.

Charcoal portraits on brown paper appear to record the individuality of each sitter, such as in “Ojibwe Woman.” A whisper of line traces the idiosyncracies of the profile; a smudge of wavy hair completes the likeness.

A few portraits include a quick rendering of the body, such as “Seated Ojibwe Man.” The posture and dress, sketched and unfinished, offer more information about the subject, but Johnson still zeros in on the face. Flanked with braids and sculpted by darkly contoured cheekbones, the man’s distinct face sheds any trace of anonymity. We might not know his name (as is the case in most of Johnson’s drawings), but we know he is someone specific.

The portraits are only one facet of the exhibit. Some of the artist’s pieces are paired with contemporary work by Carl Gawboy, a member of the Bois Fort Band of the Minnesota Ojibwe and a well-established Duluth artist. Many know Gawboy for his historically accurate everyday scenes of American Indian life from generations ago.

Gawboy has in the past turned to Johnson’s work as a primary resource for his own paintings. “Landscape of Superior” shows Johnson’s view of Superior from what is now Park Point. Gawboy referred to this image when doing a mural series showing the city’s history for the Superior Public Library. In Gawboy’s mural panel, the panoramic stretch of harbor looks mostly unchanged. Gawboy ripens the colors a bit and keenly inserts Johnson himself into the composition, depicting the artist at work on the very drawing that inspired Gawboy.

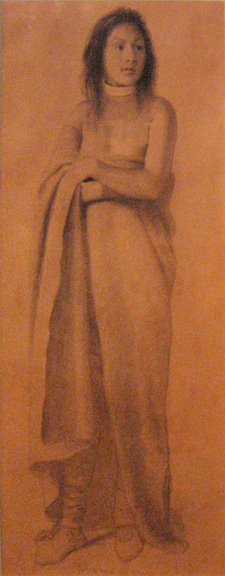

Gawboy borrows from Johnson again in “Eastman Johnson’s Woman,” a spin on a 1856-57 original entitled “Sha men ne gun” that shows a woman in typical Ojibwe dress. Interestingly, the woman’s upper chest is exposed (which would have been inappropriate), prompting questions over whether the figure may actually be a man or whether Johnson may have taken some artistic license in drawing the figure. Gawboy’s version– a stunning multimedia piece– started as a block print in 1972, when he was still a student. He revisited the print in the 1990s and added acrylic touches.

The work by Gawboy expounds the true significance of Johnson’s unpolitical eye and (as most have interpreted it) commitment to accuracy. It is indeed a strange twist of history that 150 years later an American Indian artist, laboring to depict his people with historical accuracy, relies on a white man’s vision and version.

Johnson’s and Gawboy’s drawings are joined in the gallery by a deluge of other art and information, including books, maps, beadwork, American Indian imagery by other artists and non-Ojibwe portraits by Johnson. The wall placards provide extensive background facts and a PBS show on the topic buzzes on the corner television. The Tweed clearly aims to put Johnson’s work in a larger cultural context. It’s an academic presentation– thorough and instructive.

I would have liked to just look at the art, history lessons aside, and meet each portrait’s gaze. But then I probably wouldn’t have appreciated it as much. The collection of drawings and paintings, donated by Richard T. Crane to the City of Duluth and now housed in the St. Louis County Historical Society, is perhaps too important to just look at.