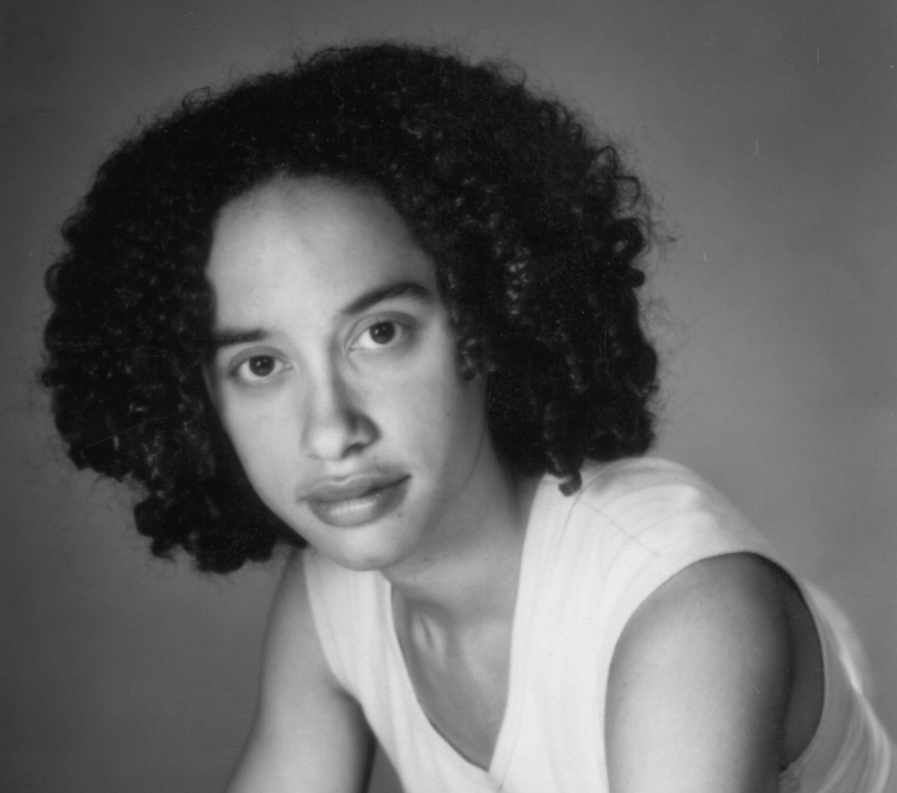

Point of View: Shannon Gibney

Shannon Gibney will be producing our new regular feature on literature, "Thinking Souls." Read her here on literature.

Shannon Gibney is a fiction writer (and Bush fellow in fiction) as well as an arts journalist and activist. She is on the board of the Twin Cities Media Alliance, is the director of Ananya Dance Theatre, and president of Twin Cities Black Journalists (TCBJ)

Tell us about yourself and how you became a writer.

I was born and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. That was a great place to grow up, because the University of Michigan is there, so there was always a ton of really smart people from around the country and around the world studying and visiting, and making art and starting and finishing projects, and getting in discussions and arguments about every kind of subject you could imagine (and some that you couldn’t). And so much of it was FREE.

Plus, there were more bookstores than you could shake a stick at, and the library system wasn’t too shabby either.

I went to Carnegie Mellon (in Pittsburgh) for my undergraduate degree, where I got a double major in creative writing and Spanish. A few years later, I went back to school to get my MFA. I choose Indiana University in Bloomington, because they had a great program that fully supported their students financially and had the most racially and culturally diverse program in the country. I got my MFA in fiction writing there, and also picked up an MA in 20th century African American literature.

As long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to be a writer. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that as long as I can remember, I have also been a voracious reader as well. For me, the two activities can barely be separated.

So I can’t think of one, formative moment that set me on the path to literature. It’s more like I have all these memories of reading everything I could get my hands on, and then making these little “books” about camping with my family and this crew of sibling detectives starting when I was around six or seven, I think.

What’s the most important thing, for you, about literature?

For me, the most important aspect of a literary work is that it tells some of kind of truth — preferably one that shakes people up.

I am not of the “art for art’s sake” school, although I do recognize the importance and validity of the aesthetic. In order for art to move me, it has to be provocative, uncomfortable, dangerous, and beautiful. There has to be something at risk, something that will cause the reader to question their fundamental assumptions. If writing does not transform, I have difficulty recognizing it as art.

What’s your favorite place in the world?

A hard choice! There are at least two: My parents’ house and land in Ann Arbor, Michigan, because our family put so much into it, and because that landscape is how I understand the world. It has imprinted itself on my consciousness in ways that I am still discovering.

The other is anywhere I’m backpacking with my best friend. The land we choose to venture into is always unfamiliar to me, always vast and feels so unknowable, but also so open. And yet, I am exploring it with someone who knows most parts of me — even the parts of myself that I have forgotten. That is an interesting and, I find, productive tension: between the known and unknown.

Do you think literary communication is universal, or bound to specific places?

I think that principles of communication are absolutely culture-bound. Nothing exists outside of culture. History tells us that people who propagate such ideas are usually trying to engineer the domination of their culture over yours (witness what Manifest Destiny did to the Native Americans, White Supremacy has done to appreciation and preservation of African and African American art forms, etc.).

Literary communication through space and place are changing right now because our culture values mobility, and technology, and is in fact reinventing the very meaning and fact of space through new “places” like cyberspace. So although we can communicate and express our art through the Internet, which hasn’t existed as a “place” in the past, I am wary of those who argue that this virtual space holds new, radical potential to cross cultural barriers and lines of communication that would otherwise not be possible (from Belgium to Ghana in the blink of an eye, for instance).

Because isn’t the meaning of the message the same, whether we’re communicating to each other from Belgium to Ghana over email, or whether I have sent it in a letter? Haven’t the power relationships between various people and nations, their access to technology, etc. just intensified with the proliferation of new mediums like chatrooms with international participants (not surprisingly, usually from the world’s richest countries)? Do we actually fundamentally understand people outside our culture because of this technological expansion of what space and place mean/are?