Point of Entry

What does it mean for an emigrant artist to call Minnesota home? We talk to Manjunan Gnanaratnam, Gladys Beltran, Xavier Tavera, and Jila Nikpay.

All artists come from a foreign country, in some sense. Where “originality” is essential, each artist becomes a world in him- or herself, with zealously guarded borders. In America, we come from all over.

My grandfather, for instance, was a musician and a writer who came here from Lofoten, Norway, when he was 17, speaking only Norwegian. He had an amazing skill with languages and was a fine pianist. Within a few years he was writing speeches for local politicians, and also essays for the local newspaper under the pen name “Peer Gynt.” Reading these texts of ecstatic melancholy, pages from a very distant book, I could see how alien this place must have felt to him–but he published them knowing that they could be heard here.

The Artists

As a small sample of the hundreds of artists from all around the world that make Minnesota their home, here are four: Manjunan Gnanaratnam (Manju) from Sri Lanka, a composer for dance; Gladys Beltran from Colombia, a painter; Xavier Tavera from Mexico City, a photographer; and Jila Nikpay from Iran, a filmmaker, photographer, and writer.

What’s it like to be an artist who makes a home in a distant land? Do people understand what you do? Why are you making art here instead of there? Is there something about this place that calls you, that needs your work? The answers to these and a thousand other questions are different for each of these artists. It turns out that “émigré artist” is not a category at all, but only a door into a very large world.

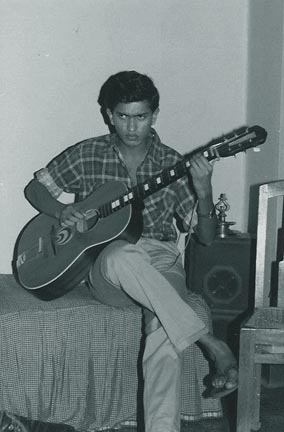

Manjunan Gnanaratnam

Manju’s current projects include plans for a 2008 performance projecting dance on the Weisman Art Museum wall, with sound improvised as the performance progresses; he’s also recreating composer Karlheinz Stockhausen’s work “Ceylon,” for live performers in transglobal locations, in 2009. He is developing a concept of improvisational music and dance inspired by an idea of the “optimal performance environment.” He counts John Cage as an influence as well as the Sri Lankan syncretic tradition.

Sri Lanka’s civil war drove Manjunan from home at 21, in 1983. He arrived in New York to study music, saw Merce Cunningham perform, and found his calling as a composer for dance.

He’s never spoken publicly about his reasons for leaving Sri Lanka: “I couldn’t talk about the effects of war until war came here—you can see wounded young people in the airports now. I can speak now about the innocence that was lost and people will understand.” He has feared that if people knew of his exile under duress, it would overshadow his work—which is not about exile, or about his nationality, but instead about the relation of human bodies and sound.

Manjunan remarks, “’Community’ has numerous meanings. In some ways, I’m more at home musically here than in Sri Lanka; the avant garde music community here understands what I do. I have a home inside my music, inside my relationship to dance, to the optimal performance environment . . . that is in some ways my true home.”

He saw his parents “broken, their home burned, devastated to be unable to keep their children safe.” They sent him to New York to school, outfitted in new clothes, as all of his had been burned, along with a guitar he cherished. “It didn’t make sense to me, driving to the airport, leaving for America . . . I was lucky to have lived 16 years in peace, and to be able to leave in 1983.

“It was difficult to comprehend that I couldn’t return. I did not get a chance to see my parents for about five years. ‘Exile’ can mean many things. Once I came to accept that… I began to focus on my future away from my friends and family.”

After being away 20 years, he returned, and realized he had missed “the vibrations of the society that produced me. Sri Lanka has 500 years of colonization by various European nations. The music contains all these traditions, church music, Hindu music, Buddhist, rock and roll–and so in some sense everything’s allowed. My physical home is in Minnesota, but my emotional home will always be Sri Lanka.”

How have Americans reacted to him and to his work? Has this changed as the political world has evolved? “A fascinating question. Americans are also different from place to place. My work as a composer for dance and performance art is easily accepted in the east and west coasts and internationally; however, I would say Minnesota lags on this.”

But does he feel understood? “Oh yes, by specific

groups….however, it doesn’t matter to me really.”

I asked Manjunan what he feels he brings to the mix of the arts in Minnesota?

“Adventure?” he responded, with a smile.

Gladys Beltran

Gladys Beltran is a Columbian painter who arrived here in 1993 with her children. She has a BFA from the University of Antioquia in Medellin, and won a McKnight Fellowship in Visual Art in 2006. In the catalogue for that show Michelle Grabner wrote, “There is an enchanting realism to Gladys Beltran’s paintings that doesn’t originate from her outer eye. Instead, Beltran’s carefully observed pictures record the idealized and ideological landscape of America.”

It took Beltran several years to learn the language and feel at home, but now, she says, “the process of growing old and the hope of growing in the spirit through my work is taking place here.” But she misses her sisters, her parents, their faces, how they change over time, their jokes and laughter. “The absence of our loved ones is a temporal death. It is horrible when you can’t hug them.”

But there is freedom even in this sorrow. “As a painter it is liberating not to be with some members of my family that love me I know, but cannot understand why I have to paint. Being away I do not have to explain over and over why I have to paint–because I have to paint if I want to breathe in peace. That I have to paint because I do love to exist.”

She returned to Colombia to visit in 2006, but sees Minnesota as her home now.

When I asked her about the reactions of people here to her work, she says it’s too soon to know: “My work is like a baby, and people always like babies. I haven’t done 1/30 of my project.”

“Few people do understand me, few people do not understand me, because only few people know about me. In the future I hope many people will be understanding me. I do wish with all my heart to make a work that is clear and will need no explanations. I wish all my work will show love.”

She thinks there is not so much difference between her work as an artist and that of her friends here; that artists are similar everywhere.

“I brought my hungry soul. My soul is hungry for my conscience to see it. Then I can say it is more what I took from you than what I brought, because I am taking your cities to paint them, I am taking your spaces to navigate in them with my paintbrushes over the canvas. In other words I will be taking over your country to paint it, to love it.”

Xavier Tavera

Xavier Tavera’s photographs have gained a passionate following in Minnesota. His portraits of men with their children; of fighters; of people with the objects of their work and passion have universal resonance. He graduated from the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana in Mexico City in 1996 and came here, at age 25, to further study photography at MCAD, in 1997. He’s shown at Exit Art in New York and at Franklin and the MIA here; he’s been a McKnight Fellow and has a piece at Franconia Sculpture Park.

Tavera does most of his photography in the large Latino community here, and it’s where he feels most comfortable. Although he’s found the community of other artists here to be welcoming, he notes that “the mainstream community is very hermetic, and won’t let you in very easily.”

“It is hard to be away from home. I am the only one [in my family] in the U.S. It is strange, I have ‘immigrant syndrome’: I don’t feel completely at home here, and I have started to feel like a foreigner when I go back to Mexico. I feel an immigrant everywhere.

“But I am fortunate to have my own family here. My wife, my two stepkids and I have managed to make a nice family.”

He misses the everyday life of home, “My parents, my sister and old friends. I also miss the food and all the conversations that we used to have after dinner.” So he tries to get back to Mexico City at least once a year.

What is the reaction of Americans to his work? To his presence in the country? Has this changed over the years? Tavera says, “So far the reaction that I noticed from Americans to my work has been very positive. But the reaction to my presence in this country has been a lot different. There is a lot of political turmoil regarding immigrants in the U.S. and specifically Mexicans. The U.S. government is building an enormous wall along the Mexico-U.S. border and the Congress can’t reach an agreement to solve the problem of twelve million undocumented workers.

“The reaction of Americans to my presence here hasn’t changed over eleven years that I have lived here. There is a lot of racism, a lot of stereotypes and too much intolerance. All of this can be solved with education.”

Tavera’s photography very traditional in its means and its purposes: it’s large-format film work that seeks to record and show humanness as fully as possible. As a photographer, he values the uniqueness of his point of view: “I think all artists have a different perspective, no matter where they were born. The difference in perspectives makes art more interesting not only for the artist but also for the spectators.

“Most of my work has to deal with people. So there is an immediate connection or disconnection to my work. I don’t feel misunderstood. I am still trying to figure out why I photograph the people and things I photograph.”

What he hopes to bring to the mix of arts in the U.S.? “I would hope a little diversity.”

Jila Nikpay

Jila Nikpay is a photographer and filmmaker from Iran who left before the revolution. Her films, often based on Persian poetry, have been shown at the Walker and elsewhere; her book Heroines, a study in photographs and poetry of women who have had breast cancer, was recently published by Orion/Zenith Services.

She left home at her parents’ urging, because they thought a degree from the U.S. would serve her better than one from home. She didn’t wish to leave but “it was something people did at that time,” before the U.S. became “The Great Satan.” Times have changed greatly, and even the word “Iran” means something very different in American than it used to.

“There is definitely a sense of liberation [to being here] but it is balanced with the anxiety of facing the unfamiliar. Being an Iranian, there is also an additional level of discomfort for me. I always feel haunted by my country’s radical and isolationist policies and uncomfortable when people talk to me about terrorism. That is when I feel constricted.”

Nikpay has recently been showing with Mizna, a forum for Arab American culture. Although she is not Arab, she felt very much at home in the group. She misses “the way Iranians socialize, their outward warmth and generosity, the poetry, and the sense of history that is everywhere. As a land, Iran has seen both glory and misery, that experience has given it an ancient, melancholy soul. I miss that very much.”

But an unbridgeable gap has grown: “I have only been back twice since the revolution. As much as I love Iran, It is hard for me to witness from a distance the changes that have overtaken my country. Once you leave and lose your country like I have, the idea of home becomes more abstract.”

Her own work struggles with the distances between her home culture and her present place; as she incorporates Persian and Iranian themes the work becomes harder for American audiences to grasp. “There is tacit expectation that if your work deals with the Middle East it should be politically correct and you must treat the subject superficially. This presents a serious dilemma for me,” Nikpay comments. Her own stance as someone who is assimilated is a balancing act.

“One strategy of survival in Minnesota I have gradually adopted is that of projecting an image of a well-integrated foreigner, camouflaging my presence. At the same time, over the years people have learned where Iran is on the map so they no longer ask me where it is or want to know about it.”

Nikpay knows that her position between cultures gives her a perspective unavailable to those with less complicated backgrounds; does she feel that people here get her work?

“Living within two cultures that don’t see eye to eye requires walking a tightrope. The more my work has become specific in its subject, the less it is understood. Dialogue is essential for this type of work because it needs to be decoded and in that process a deeper understanding of cultures can take place. Surprisingly, I have found that this is a lot to ask from most people; stereotyping cultures is much easier.

“At this point I am moving forward with a new work. My upcoming film, In Waiting, is not culturally specific, and although it draws from Iranian sensibility it is more about contemporary global issues.”

I asked Nikpay what her perspective brings to the mix of the arts here. Her response revealed the blind spots in our own perspective: “On a most rudimentary level, most immigrants can see what most natives don’t see in their own culture because of its familiarity. On the grand scale, history reveals that even the largest countries, like America, were founded by wanderers. Therefore artists who can elaborate and expound upon this experience are in their own way keeping the American spirit alive.

“The contemporary world is filled with the sense of uncertainty, contradiction and multiple realties. These very conditions look a lot like the experience of being uprooted and being thrown off one’s center. My work speaks of all of these experiences because I know them very intimately and that is what I bring to the mix.”