Pictures of Change? U.S. Social Forum

Shannon Gibney attended the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta, Georgia, at the end of June, and came away with this report on art in the service of social advocacy.

The U.S. Social Forum (USSF) was a nationwide conference held in Atlanta, Georgia at the end of June. Its organizers wrote, “The US Social Forum is more than a conference, more than a networking bonanza, more than a reaction to war and repression.” It was an outgrowth of the recognition at the World Social Forum that the solutions to many of the intractable problems in the world lay of necessity in the hands of U.S. citizens. –ed.

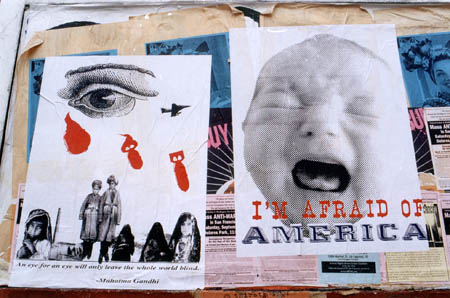

The notion that art can change people’s minds, and in doing so can change societies, is quite an attractive one – which might explain its staying power. But at a recent panel at the U.S. Social Forum, a lively debate about the efficacy of this strategy was ignited.

The panel was titled “A Hammer to Shape Reality: Art and Social Movement,” and was organized by the San Francisco Print Collective (SFPC), as well as by Liberation Ink, a T-shirt and garment printing company, and Just Seeds. These are all visual arts and social justice organizations which have taken different but related courses in using visual imagery to change peoples’ thinking about their world.

“What we were doing was very much shaped by a year of campaign work. There were people in the streets, public meetings, and the images themselves,” said Fernando Marti, of the SFPC, explaining the group’s 2000-2001 campaign to highlight the problems faced by residents in San Francisco’s Mission District.

“We were working with the homeless coalition, working with South of Market around a different kind of displacement,” Marti continued. “The Mission District was becoming increasingly gentrified. The Collective made posters, but also did other art projects. We worked with neighbors to define how they wanted to see their neighborhood. They created a ‘People’s Plan’ to define what the community wanted to see in their neighborhood in terms of housing, transportation, education, etc. So the basic strategy was to integrate the images into other organizing elements. We never intended for the images to do that work on their own.”

This multifaceted, multi-pronged coalition helped the SFPC’s images convey the power and voice of an otherwise unheard community. This in turn forced local politicians and developers to respond, and take action.

Josh MacPhee, the mind behind Just Seeds, which bills itself as a “visual resistance artists’ cooperative,” offered another view of the art and social justice conundrum.

“I think there are two kinds of conflicting truisms: One is that you can’t confuse representations of direct democracy with direct democracy. You can’t draw the new world into being. But the flipside of that is that culture is so big and messy that you don’t know how things are going to impact communities, or what they’ll mean to various people. So it’s about finding some balance for yourself while you’re trying to negotiate it. And part of that is about sharing your work with people before you put a lot of time and energy into it. I know a lot of people who have rolled out 1,000 posters that were completely misunderstood because someone didn’t just get on a bus and ask people, ‘What does this mean to you?’ So doing your research and development is well worth it.”

MacPhee has been doing just that in Chicago, for a while now. He initiated the “Celebrate People’s History Poster Series,” which includes “Mothers of East Los Angeles,” “The Silent Majority,” “El Agua is Nuestra Carajo,” and “Fred Hamption 1948-1969.”

“We have produced 44 posters so far, and they are close to being able to produce around 10 a year. Different artists do each one, and it’s a way to build a network,” said MacPhee. “The posters were inspired by a bunch of my friends who were teaching in the public school system and had absolutely no materials to use to engage their students.”

Toward the conclusion of the discussion, an audience member posed a related question, about how to keep mainstream/capitalist forces from appropriating images – a process that is becoming more and more pervasive with every Malcolm X image printed. Le Tim Ly, of Liberation Ink, “a worker owned apparel printing and design collective created to fund social justice organizing” in the Bay area (www.liberationink.com), said, “At Liberation Ink, we try to place all our images in time and space. We go deeper than just an image by including text. So if we had a t-shirt of Che, we would include something significant that he said.”