Piano Life

Our jazz columnist, Jeremy Walker, muses on the contributions of two very different, but equally gifted pianists whose playing has left a lasting influence on his own: David Berkman and Marcus Roberts.

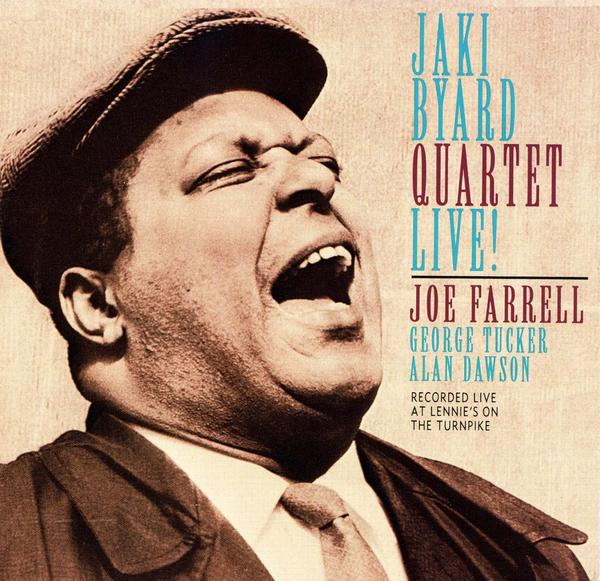

JAKI BYARD. Anything written about pianists needs to mention Jaki. He will probably come up again, actually, even though this piece is primarily about Marcus Roberts and David Berkman, two pianists I have been listening to a lot lately. Roberts is noted for a career in which he’s deliberately moved through the whole history of jazz piano, from ragtime forward. There are plenty of people who have dismissed him for his choice to look back in that way (although I have never heard anyone fail to appreciate his pianistic gift). David Berkman, on the other hand, is a completely contemporary pianist, known for challenging music, deep harmonic sophistication, and restless improvisation.

Right now, these two, very different musicians are my favorite pianists out there playing.

Berkman came to New York in 1985 from Cleveland, which is only interesting in so far as it relates to his music. First: the fact that he moved in 1985 is important, because New York at that time was being overrun, dominated by a group of musicians playing aggressive, acoustic, difficult music. (For a superb essay on ’80s and early ’90s jazz, read Ethan Iverson’s article on the so-called “young lions”.)

Like Berkman and most musicians my age, the jazz of the ’80s initially influenced me a great deal. Listening to it today, though, most of it doesn’t interest me. I don’t want to discount the real achievements of the time, but a lot of stuff I used to love sounds dated to my ear now. Plenty of those musicians could play, no doubt. Harmonic mastery, rhythmic drive and accuracy, and of course virtuosity are lasting legacies of the time. But, to me, much of what I hear in that era’s jazz sounds to me like a musical equivalent of a the Cosby sweater. I mean, we all loved them at the time, but they’ve aged badly.

Berkman wasn’t a “young lion.” He didn’t get much press or big record contracts. He did, however, gig all over town, working hard on developing his sound and musical language. The music he writes is interesting and challenging, and he has recorded and performed with a lot of great horn players over the years. He can deal with the full range of jazz piano harmony, and is capable of the same sort of lush, introspective sounds that Bill Evans is credited with. But Berkman also deftly deals in the angular modernism that Herbie Hancock brought to the highest levels. He is a very funny guy, too, verbally gifted, with a sense of droll self-deprecation that seems at odds with the brash confidence of his keyboard mastery.

Berkman has also been an important mentor to me. His book, The Jazz Musicians Guide to Creative Practicing has played a significant part in my development on the piano. He also hipped me to Abby Whiteside‘s book, Fundamentals of Piano Playing that helped me get to a more percussive attack at the instrument.

All of that is great but, for me, it’s not really what keeps me involved in his music. There’s a deeper level of affinity I feel for his playing that, for the sake of narrative, let’s say, has something to do with Cleveland. This might just be an aesthetic fantasy of mine, but however far his music gets harmonically, it always seems to me to be connected to a blue collar, rust belt pragmatism. I’m not coming up with the idea out of nowhere: Cleveland has always been known as a hard bop town. For those of you unfamiliar with it, hard bop was a style of jazz prominent in the ’50s and ’60s, characterized by bluesy, hard-driving swing. I love it — Tina Brooks, Hank Mobley, Art Blakey, Clifford Brown, all of it. And it’s not just me; those Blue Note recordings are the very definition of jazz for a lot listeners.

So, this Cleveland, hard bop thing might be narrative fiction on my part, but I still find it instructive when looking at Berkman’s music. All his technique and harmonic sophistication, his restless imagination, and the high ambition he brings to his music happen in the broad territory of blues and swing. And it is this head-in-the-clouds/feet-on-the-ground quality that makes his playing so engaging for me. Although he has primarily recorded his own compositions, usually accompanied by horn, it’s his solo and trio playing I love best. And when he is dealing in blues and standards, the grounded quality of his aesthetic ambitions are all the more clear.

This common language, of blues and of swing – that groove — is the connecting thread between Marcus Roberts and Berkman. Since Roberts’ earliest recordings with Wynton Marsalis, it has been clear he is a stylist of the highest order. And it is also clear that he has always brought his own distinct musical concerns to the table. Roberts’ work on Marsalis’ J Mood, Marsalis Standard Time, and Live at Blues Alley have served as rallying cries for a whole generation of musicians. It’s clear to me that Marsalis’ work took on a whole new range of ideas and feelings once Roberts came into the band.

______________________________________________________

What Marcus Roberts has done has less to do with looking backward than it does with digging deep. His music is fully modern and deeply personal. His harmonic command, his sense of rhythmic adventure, and his structural innovations in the traditional jazz piano trio are huge and under-regarded.

______________________________________________________

Two earlier recordings that still knock me out: Roberts playing on Marsalis’ Thick in the South (with the great Joe Henderson on tenor and Elvin Jones on drums); and his first work as a leader, The Truth is Spoken Here, the first track of which, “The Arrival,” stands as a high point of that generation’s work. It didn’t hurt that he was accompanied here, too, by Elvin Jones who was playing some of the hardest swinging, thorny brushwork I’ve ever heard. Another track on that album, “Country by Choice,” also swings hard enough to serve as an aesthetic and geographic manifesto. (When I was playing saxophone, I spent a long time transcribing Charlie Rouse’s masterful solo.)

Roberts was expressly interested in “looking back” into the history of jazz and the piano. So I am clear, I actually think the phrase “looking back,” as it’s often applied to the kind of music Roberts put out, is myopic and dismissive. Just because something happened a while ago, doesn’t make it an antique. “Looking back” puts dealing with Scott Joplin in the same category as dressing up in old west clothes for a sepia-toned family portrait. Let’s come up with another way to talk about what he’s up to: what Roberts has done has less to do with looking backward than it does digging deep. His music is fully modern and deeply personal. His harmonic command, his sense of rhythmic adventure, and his structural innovations in the traditional jazz piano trio are huge and under-regarded. I must admit, I slept on what he’s been doing in recent years for a long time. Initially, I felt he had stepped back from the territory he gained on earlier records.

I was wrong. Marcus Roberts aims for music that transcends its time. He possesses total mastery of the piano, with a deep sound and strong independence between his left and right hand; he is able to play behind horns inventively without intruding on their space, and he uses the whole range of the piano. He is also one of the most deeply soulful people I have met, and he’s able to make his far-reaching ambitions both deeply felt and enjoyable. To paraphrase David Berkman speaking admiringly about another musician: Roberts plays past the critics and musicians and right to the audience.

THERE IS NOTHING PARTICULARLY SURPRISING about the fact that two seemingly disparate musicians have been so influential to my own playing. Jazz is about together. In the common history and vernacular of jazz, there is room for all sorts to deal with music together. In fact, jazz is often at its best when there is an aesthetic tension being negotiated. The common thread between these styles is expressed in the blues, and in that certain rhythmic drive that peculiar to jazz. But there’s room for anyone willing to meet up there and play.

And another thing: both Berkman and Roberts play with authentic feeling, and are capable of heart wrenching emotion — human fears, love, regret, all of it. Both musicians lay it bare in front of you, and do so with an instrument that is more machine then any other. The grand piano has 4600+ parts; there are 46 parts between the pianist’s finger and the string. And yet, Berkman and Roberts bring an immediacy to their playing that cuts right to the heart of the matter. That is at the center of all art, not just jazz — human connection and communication. That is why we do it. It’s why we keep coming out.

I should mention another connection between these two: the late Kenny Kirkland. Kenny was in Wynton Marsalis’ first band, and he is almost universally counted as an influence on just about everyone who’s followed. Again, harmonic mastery was in place. Technique and touch too. But he had this distinctive, rhythmic feel, too – something all his own. And I can hear that influence all over: David Berkman knew him and followed his music, and Marcus Roberts followed him into Wynton’s band and was well aware of his achievements. Kenny Kirkland is missed.

*****

So, some recommended listening:

Marcus Roberts (on all of these, listen to his solo piano work. Phew!)

The Truth is Spoken Here.

Blues for the New Millennium

From New Orleans to Harlem

Gershwin for Lovers

*****

David Berkman

Leaving Home (his performance of “Embraceable You” is one of my favorite solo piano performances in recent memory)

Live at Smoke

Also, his next record is going to be great. David’s been doing some of his best playing lately. Look out!

______________________________________________________

About the author: Jeremy Walker is a composer/pianist based in New York. He has performed with Matt Wilson, Vincent Gardner, Wessell Anderson, Marcus Printup, Ted Nash, Anthony Cox and other notable musicians. He was the owner of the now defunct club, Brilliant Corners and co-founder of Jazz is NOW! in Minneapolis. In April 2011, Walker stepped down as Artistic Director of Jazz is NOW! to focus Small City Trio in Minneapolis and several new projects in New York. Small City Trio just released their first album, a collection of original songs by Walker called Pumpkins’ Reunion, available digitally on iTunes.