Paying Attention to an Other

Thomas O'Sullivan describes the rich variety in the "Fresh Cut " show of botanical art at the Weisman Museum. Botanical art is having an excellent run this fall--check out the show at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum as well.

The Weisman Art Museum is playing host to a sparkling and, in this venue, surprising array of botanical art and illustration this summer in “Fresh Cut.” Exhibitors are members of the American Society of Botanical Artists, an organization representing the best of the genre. Selected by a jury of two practicing artists and Weisman director Lyndel King, then vetted for correctness by a university botanist, “Fresh Cut” features paintings and drawings that display “scientific accuracy, technical skill, and aesthetic quality.” Minnesota artists fared well in the blind judging, comprising seven of the 52 accepted MSBA members: Wendy Brockman, Kathleen Creger, Jane Ferguson (Otis), Julie Ann Martinez, Mary Anne O’Malley, Lyudmila N. Pavlova, and Timothy Trost.

Botanical art as an expressive genre has had an international renaissance in recent years. More than scientific illustration and different from flower painting, it is a nature-based realist art form with essential ties to science and tradition. The old saw “truth to nature” is held here to an exacting standard, a visual equivalent to the nomenclature on each work’s identifying label: not just “rhubarb” but Rheum raponticum, for example. Marilyn Garber, artist-founder of the Minnesota School of Botanical Art and chair of the “Fresh Cut” organizing committee, has characterized the purist approach of the ASBA members, as compared to artworks like the Weisman’s Georgia O’Keeffe flower paintings, as “the difference between Beethoven and jazz.”

While the field as a whole chafes needlessly at defining its niche—like countless subgroups of the art world, from wildlife painters to conceptualists—individual artists produce pictures that transcend debate. Corinne Lapin-Cohen’s “Gingko” exemplifies the fierce concentration of contemporary botanical art, with a sly nod at the conventions and origins of the genre. She flirts with trompe l’oeil in painting the slots of a paper specimen sheet that would hold an actual plant in a herbarium collection, as well as the minutely observed leaves and fully-modeled fruit (with one sliced open to display its seed).

Most of the “Fresh Cut” artists work in the documentary tradition that identifies a plant in all its particulars while revealing its utter wonder. The aforementioned rhubarb by Hillary Parker is lovingly portrayed from exposed root hairs to frilly flower tops. Parker’s treatment, with undulating leaves and foreshortening from below, imparts a Jack-in-the-beanstalk magic to her three-foot-high watercolor. Martinez’s portrayal of bunchmoss is botanically complete down to the fine pencil details flanking the radiating stems and sinuous tendrils of the plant. Several artists, like Katherine Shimada and Carol Woodin, have lettered the plant’s common and scientific names into their pictures, an elegant touch and a nod to the long book and print traditions of botanical art.

Virtuosity in drawing may be a prerequisite for ASBA membership and exhibit success, but “Fresh Cut” confirms the sheer pleasure to be seen in the craft. Ann A. Fleming and Martha G. Kemp’s drawings can serve as case studies in not just botany but pencil technique as well. Kate Nessler’s entries demonstrate the challenges and satisfactions of vellum as a ground for a mix of drawing media. In the show’s largest drawings, Nancy Kuo Ho shows her mastery of modeling and space in velvety penciled line and tone. At the same time, technique for technique’s sake is not enough: a few works, like Brenda Nass’s acrylic chokecherry, seem too harshly photographic to be satisfying.

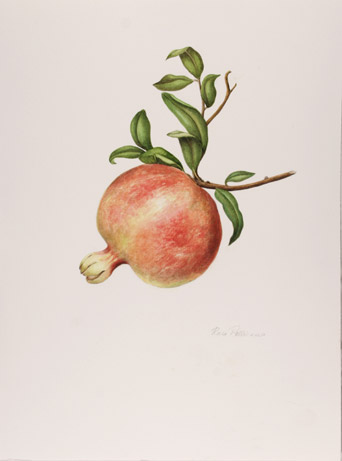

The exhibition offers ample opportunity to compare how different artists approach similar themes. Rose Pellicano’s watercolor of a pomegranate hangs buxom on its freshly-cut twig; Carol Till renders the fruits at a more ripe and ready state, with seed spilling from a slice in the foreground. Artichokes (which like pomegranates are popular subjects, Garber notes, since they don’t wilt quickly) by Toshi Shibusawa and Morgan Kari offer portrait-like studies in close observation. Magnolias are present in surprising ways: Camille Doucet adopts gold leaf and a close-up viewpoint to explore a sumptuous blossom, while Barbara Oozeerally intimates the promise of a future flower in her exacting watercolor of a seed pod.

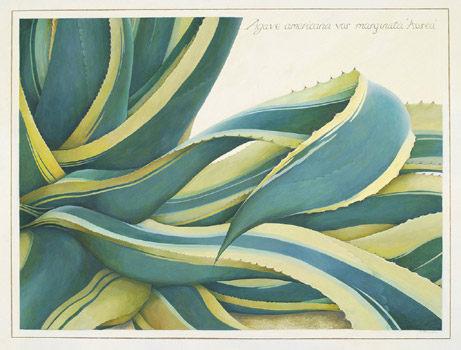

The exhibition demonstrates how variety and personality can flourish within the tightly defined protocols of the botanical tradition. Several artists explore the expressive detail, rather than portray the specimen in full. Rita Parkinson’s study of an agave is large for the genre at almost four feet wide, and zooms in on an apparent tangle of striped leaves; closer inspection shows the logic of the growing plant with its spiky edges and fleshy leaves. Shibusawa’s square watercolor of six leaves highlights variations in color, size and veining to individualize the American smoketree while illustrating its typical features. Sarah Roche’s watercolor of lichens on oak twigs is a study in delicate color, with the mystery of a medicine bundle.

While the typical botanical picture revels in lush color and perfect bloom, the brown and withered specimen holds its own magic for many artists. Kevin Duggan paints a lineup of dried goldenrod galls as a lively composition of spent exuberance. A group of three prairie plants by George Olson is a tour de force that seems to crackle to the ear as well as the eye. Bobbie Brown and Sally Markell find poetry in seed pods and pine cone, suggestive of life forces in a season of rest. All are ready reminders of the rich cultural humus in which plant imagery is rooted, eloquent beyond Victorian clichés of the language of flowers.

A few pieces in “Fresh Cut” stretch the botanical-illustration imperative surprisingly far. Sara Gilbert uses both collage and decorative patterning in her “Bulbophyllum Friends,” while Arundhati P. Vartak and Sandra L. Williams exhibit fully-fledged landscape settings, complete with animals. Pleasant, skillful enough, and unremarkable in most contexts, such works here pose the kind of question whispered between two exhibit-goers: “That would be an easy piece to live with, but is it botanical?”

Part of the fun of viewing “Fresh Cut” is the notoriously postmodern Weisman, a venue better known for exhibits like this summer’s concurrent show of L. A. artists associated with architect Frank Gehry. The botanical show is spaciously hung in three high-ceilinged galleries, with thoughtful juxtapositions that make the most of the modest, yet telling variations within the genre. The earnestness of the work is infectious. The sight of a gallery visitor using a magnifying glass—unthinkable elsewhere in the museum—makes perfect sense before the virtuoso lines of Carol E. Hamilton’s lavender plant. If the richly compressed skill and vision of “Fresh Cut” urge visitors to let their guard down, all the better for their enjoyment of art’s abundance in the tragically hip world outside the gallery walls.