Parallel Play at Off Leash Area: Maggies Brain

Any production by Off Leash Area is an event: this group consistently pulls together extraordinary talents from all over town to produce performance that is dance, installation, theater, and concert in one. Maggies Brain is no exception.

Jennifer Ilse’s brother became schizophrenic when she was a teenager. She watched his abduction by his own mind into a parallel world; an abduction that was both torment and, occasionally, rapture. And it was absolute. Like an eighteenth-century immigrant or a space traveler, for him there was no going back. The performance “Maggie’s Brain,” which Ilse co-wrote and co-directed with Paul Herwig, is a take on that. It doesn’t tell Ilse’s brother’s story or try to explain it. Instead it’s an exploration of what that alien territory might possibly be like, an exercise in full-body empathy that is much more than emoting.

The performance opens with a masterful set piece that provides the key for the rest of the evening. The happy family is arriving home, sitting down to dinner, recounting their successes, conversing and performing for each other, clowning around. Maggie (Ilse) isn’t there. She’s called, and finally fetched. Her slightly bizarre behavior visibly frightens and even repulses her family, After a final explosive paranoid outburst from Maggie and the family’s outraged and wounded response, the opening scene is “rewound,” run in reverse, in a virtuoso turn that is spot-on. Then the whole thing is re-run from inside Maggie’s perceptions, including actors playing the voices that force her into the behaviors and gestures and thoughts that have set her family opposite her.

These parallel realities form the structure of every following scene, though never again so symmetrically. “Maggie’s Brain” is trying to expand the territory of human understanding by giving us a bodily experience of mental illness—of absolute otherness.

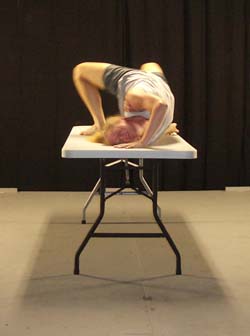

The ways the troupe does this are often shockingly fun to watch, though harrowing as well. Every participant deserves credit for the ensemble-dependent performance. The dancing and the athleticism are a clear joy.

Kim Longhi’s costume design is both obvious and subtle: Maggie has two families: the “real” one (clothed in subtle and varied shades of grey) and a parallel “family” who provide the illusory voices in her head—clothed far more vividly in black-and-white with bright reds, oranges, and yellows, more vivid, scary, and amusing than their doppelgangers. Maggie herself wears “human” colors, tans and browns, as does (eventually) her psychiatrist, when Maggie has eventually been hospitalized (and dressed in cold blues). The costumes are evocative and interesting, the color a clear guide to the structure of the piece.

Ben Siems’ sound design, in this highly complex pantomime, makes clear the trajectory and context of the sometimes ambiguous movement: percussive sections clarify compulsions, an echo moves in when spatial disorientation follows on the sudden opening of vast spaces inside the body of Maggie, who magically contains multitudes when she enters the realm of the voices. When she turns outward and the world gets little, nagging repetitive patterns don’t let us escape a visceral knowledge of the contraction. Siems uses many more of these gestalt devices, which provide syntax for the movement, enabling it to engage one’s visceral senses.

Jennifer Ilse as Maggie and Judith Howard as Maggie’s psychiatrist pull off a kind of tango that moves from their bodies to, finally, their gazes. Their performance is not a matter of imitating emotion, but of replicating forms of movement that we know mean certain things. What’s the difference? A lack of wishful thinking. No sentimentality, though lots of empathy.

There’s more conventional acting in the play as well. Maggie’s charmed play with her voices (when they are her companions instead of her tormentors) is one example; her long feet playing with a rope extended for her by her “voices,” the intent amusement on her face, are moving. The bravura section in which her family members enact, in more and more anguished and frantic forms, their attempts to reach her is another. But “acting” in this work is formalized, turned up a notch. It’s a bit mad, and the madness is contagious, even though I also could stand back and see it from a distance.

Do go and see this thing if you can; it’s well worth your time. It runs through February 3, Thursdays through Saturdays, 8 pm, at the Playwrights Center, 2301 Franklin Avenue E, Minneapolis. Call 612-724-7372 for tickets. If you can’t make this, Off Leash is doing a Warhol-inflected piece of fun and games in July at the Southern called “Our Perfectly Wonderful Lives.” I look forward to that . . .