Offstage: A Career In Dance

Dance writer and educator Camille LeFevre offers an insightful review of a new book on the lives of dance professionals--from critics, to academics, to choreographers--and in the process, she reflects on her own life in dance.

JUST A FEW WEEKS AGO, I WAS ASKED the question againthis time by Senator Norm Coleman and his wife Laurie (at a dance benefit, no less): How did you become a dance critic? As I smiled and revved up the story for telling, their attention was quickly whisked away to more pressing matters. No worries. After all, the conversation was abuzz with talk about dance, dance schools, the role of dance in childrens education. It was an enlightening peek way, way behind the curtain, where politicians, lobbyists and performance professionals partner in their own dances of power and argument, compromise and conciliation.

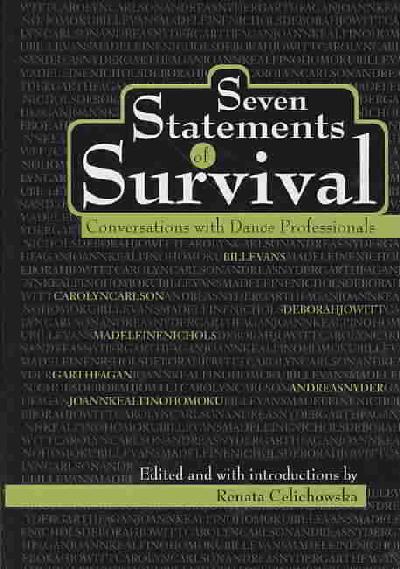

Id like to suggest they all read Renata Celichowskas Seven Statements of Survival: Conversations with Dance Professionals (its easy to whip through in a couple of hours), a behind-the-scenes look at how an array of professionals have carved out lives in dance. The book was inspired, in part, by Selma Jeanne Cohens The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief published decades ago; Celichowska’s offering serves as an homage and as way to inform a new generation of dancers, leading them toward careers in dance where they can work in capacities other than performance. An educator, scholar and former performer with the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, Celichowska has chosen her subjects in a way that provides a prismatic view on the ways people work in dance sometimes on, but mostly off the concert stage.

Celichowskas interviews all revolve around the same fundamental questions: Describe what you do. Is dance a profession, a passion, a calling? Who are your mentors and influences? Life landmarks? How have you gotten where you are today, and what is your advice for the next generation? What are your hopes and dreams for dance? Seemingly captured word-for-wordthe author records their answers complete with hmms, ums, yada yadas, and I dont knows. As a result,the interviews have an immediacy that’s imbued with the personality of the speaker.

Deborah Jowitt, long-time dance critic for the Village Voice and one of the interview subjects, is thoughtful and self-aware while contemplating her work as a dancer, choreographer andthrough coincidencecritic. Just as importantly, she’s candid about sharing her regrets. Carolyn Carlson, who danced with Alwin Nikolais in the late 1960s, then moved to Europe to direct a number of companies before settling in at Atelier de Paris-Carolyn Carlson, is self-congratulatory. Andrea Snyder, the former assistant director of the National Endowment for the Arts dance program and president of the service organization Dance/USA, provides a lively synopsis of her education and career as an administrator, and she discusses changes in funding.

Bill Evans describes how his stellar career as a dancer and choreographer has been largely felled by personal problems fueled by homophobia and lack of self-esteem. But he also, with tremendous grace, talks about the gifts inherent to teaching and his belief that every child in our culture deserves the experience of dancing. Madeline Nichols, who curated the dance collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center from 1988-2005, talks about working within a bureaucracy, technology and dance preservation, and the doggedness of the best dance historians.

Celichowskas interview with the entertaining Garth Fagan, alone, is worth the purchase price. A delightful raconteur who eschews political correctness, the Jamaican-born choreographer and dancer is laugh-out-loud funny as he describes his loathing for fabulous preparations in ballet that produce only two poopy little leaps and two pirouettes. Fagan laments the lack of testosterone in contemporary dance: I mean, Nureyev was as gay as a Chinese funeral, but he was male. He rails on the need for discipline (indeed, one of his signature pieces is Prelude: Discipline is Freedom), and he describes his straight arabesque; he reveals the tension in his relationship with his father and discusses the pros and cons of working in Rochester, New York. Fagan’s exuberance and intensity leap from the page with the same vigor as his earthy, muscular choreography.

The dance professional I was most curious about, however, is scholar and anthropologist Joann Kealiinohomoku. Her groundbreaking essay, An Anthropologist Looks at Ballet as a From of Ethnic Dance rocked the dance history, education, and criticism communities when it was first published in 1970. This much-anthologized article is also a cornerstone in my thinking and writing about Western and non-Western dance forms, and has informed my teaching about dance as a manifestation of culture.

In her conversation with Celichowska, she observes: The West tends to be more interested in other cultures than other cultures tend to be interested in the West. This and other similar comments are like pebbles dropped into a still pool, whose ripples I want to follow to some far exhilarating shore of scholarship.

Accounts of her academic travails remind me, once again, how much easier graduate school is now for women, and women in the arts particularly, thanks to trailblazers like Kealiinohomoku. And her recollection of the Yaqui Deer Dance, while brief, is packed with eloquent detail of the sort cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz calls thick description.

While Celichowskas subjects fall into a variety of categories, from choreographer to critic and scholarcuriously, she has not included a dance presenterall of them have long biographies that also touch on their respective work as educators, poets, college professors, dance-program coordinators, attorneys and authors. Still, each of them identify themselvesfirst and foremostas dance professionals.

As do I. Dance criticism, dance scholarship, dance advocacy and the occasional teaching gig occupy most of my time and energy, and thus form my identity in the world-at-large. But its my architecture writing that pays the bills. Then why do it? is the incredulous response I often receive after explaining my work life. Like Kealiinohomoku says, its the possibility of expansion inherent to danceintellectual, emotional, cultural, and sensoryembodied in the kinetic experience that attracts me. The chance of finding oneself filled with it all, whether watching dance on a concert stage, at a pueblo, in an art gallery, or in a historic buildingthat’s the impetus for it all.

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a St. Paul-based dance critic and scholar. Please visit her website at camillelefevre.com.

Seven Statements of Survival: Conversations with Dance Professionals ($24.95)

Dance & Movement Press (Rosen Publishing)