Not Easy to Take: “Safety Club” at Midway

Patricia Briggs was struck by Todd Norsten's show "Safety Club" at Midway Contemporary Art's new space in Northeast Minneapolis, and driven to think about the long and resonant development of this artist's career. Show is up through October 21.

Todd Norsten’s new paintings are not easy to take. That is to say, they flatly refuse to give viewers what they think they want from painting. The perceptiveness of this refusal makes them both prickly and thoroughly interesting.

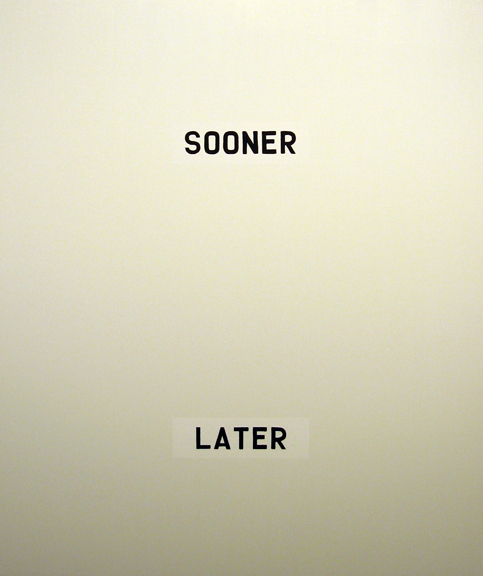

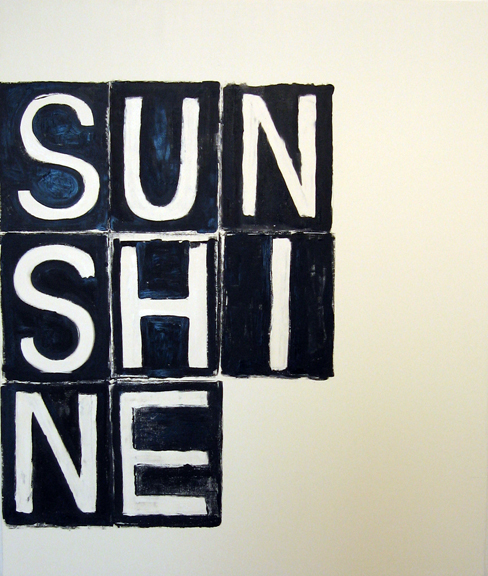

All these large paintings, measuring roughly six and a half by five and a half feet, proffer a creamy white carefully painted ground—the hygienically presented and frightening tabula rasa of painting— numbly articulated with a stark hieratic image. One features a ridiculous spider, like an earnest doodle drawn in a grade-schooler’s notebook; another shows the silly cartoon face of a menacing girl with two goofy pigtails sticking up from the top of her head—also the stuff of spiral-binder marginalia. There are slogans and accusations. An iconic T-shirt with the words “repent or perish”; a naïve billboard-like painting with a crucifix declares: LOVE, MERCY, GRACE, FAITH, HOPE, LOVE. There’s a painting done in two tones of white with the angry phrase YOU ART FUCKERS awkwardly squeezed at the edge of the canvas. One is taken aback by these paintings’ mode of address.

Yet no one should mistake Norsten’s paintings for childish pranks or gratuitous brutishness—unless they believe that a self-conscious consideration of painting as a practice deserves that charge. A painter’s painter, Norsten has for years been involved in an exploration of the philosophical terrain inspired by the medium.

In the late 1990s when I first encountered his work he was producing large seemingly decorative canvases “painted” largely without brushes. Employing rollers and squeegees and stamps—in one instance he had the round burner of an electric stove made into rubber stamp he used to print paint onto his canvases—Norsten went to great lengths to avoid performing the painter’s touch, that painterly signature charged with aesthetic and philosophical baggage.

As a printmaker he tirelessly toyed with the problems of perception and representation, turning the rules of perspective upside down, projecting impossible volumes into the chimera we call pictorial space. This was, and is, all smart and beautiful work. Still, as much as he resisted the earmarks of expressionism, these works read formally as modernist pictures—they were entrapped, one might say, in the vortex of painting’s enfolding history.

Next, Norsten turned to casting stretched canvases in resin, produced paradoxical sculptures that both perfectly represented painting and absolutely rejected it. In a sense, by producing these ontologically complex objects—paintings that aren’t really paintings—Norsten underwent his own minimalist phase, and just as the historical movement of Minimalism did, he enacted his own “death of painting.”

In the recent work Norsten emerges from that provisional termination with a new orientation. Turning away from tradition–a carcass he has lovingly picked over for the last decade–for the past few years Norsten has been drawing “pictures.” Taking the place of the earlier platonic shapes are iconic images–silly stylized pictures, pictographs of things that are perfectly abstract but thoroughly familiar—letters (they are themselves abstractions) that tenuously form words, and bland ironic or aggressive phrases. Norsten doesn’t think of these smallish drawings as individual “works”: last year at Franklin Art Works he exhibited dozens of them as a single sprawling piece.

But however clearly these drawings announced the artist’s new direction, at the time it was hard to make out their meaning or their raison d’être. Could the barrage of images be an exploration of the artist’s psyche? Do these drawings derive from some unsavory masculine version of a Louise Bourgeois-esque automatic process? The Midway exhibition with its deadpan translations of Norsten’s drawings into large-scale paintings puts the question to rest, and the answer–well, the answer is no.

The restraint and slight broadening in scope of the imagery makes Norsten’s concerns more accessible in the Midway exhibition than they were at Franklin. The grotesque zeal of the drawings shown at Franklin Art Works, which were populated by clunky jack ‘o lanterns and snowmen dripping blood, has been slightly squelched and this makes it easier to see that Norsten is exploring a certain category of the contingent image. No longer disparaging the representation of things, Norsten has turned to look outward into the world populated with a cacophony of signs with the same scrutiny that he used to apply to the material and conceptual paradigms he’d inherited from painting’s modernist history.

Unlike so much contemporary painting, Norsten is not jumping on the neo-pop bandwagon; instead we see a fascination with the way that humans take up line and shape to say things in very basic ways, in ways that barely make sense yet are completely understandable. There is a kind of juvenile single-mindedness and audacious stubbornness in this class of images that resist both the language of the aesthetic (fine arts) and the language of the commodity (advertising). This is not faux-naivete, but rather the record of a scrutinizing and hungry vision, fascinated by a marvelous quality of the image as a tenuously constructed and strangely provocative gesture. Thus, barely perceptible lines scrubbed onto a canvas slap the face of the viewer: YOU ART FUCKERS—the sting smarts all the more as the insult is employed within the context of a posh art gallery. Letters arranged on a page/ground teeter on the edge of becoming words; in one untitled work pasty block letters which could spell out the word “sunshine” are stacked in three rows one on top of the other— SUN, SHI, NE—as if the artist is unraveling the possibility of their potential meaning.

This isn’t dry conceptualism or an artist simply playing with semiotics. Norsten seems interested in the impulse or drive to deploy images—he’s interested in the kid scribbling in his notebook, the Christian zealot painting a home-made sign on the side of a barn, the antagonist or aggressor throwing insults. Instead of seducing the viewer, as paintings traditionally do, Norsten’s recent work positions the viewer at a disadvantage, forcing him or her to grapple with inelegant yet familiar signifiers that operate in the world in interesting and surprisingly unsettlingly ways.