Nesting in the Struggles of Unrest

An ode to the bed as place of solace and unfettered imagination, a refuge from which to seek guidance from ancestors, and a ground for survival in times of pandemic and uprising

My bed has always been my happy place.

I was often sent to my room as punishment for some childish misstep, or as a respite for an overburdened adult fatigued by my questions, endless needs and wants, or my very existence.

I was often in my room long before the sun relinquished her role of warming and illuminating all living things. I listened to the neighborhood wind down: people coming home on foot and cars, doors opening and closing, voices lifting to greet and share the day, and dinner starting with the clank of pots and dishes. When satiated, women or children watered lawns and men turned TVs on to watch the news. It was my nightly soundscape. I imagined a grand symphony of hissing, sunning snakes telling me good night.

I didn’t mind.

My bedroom, bland, absent of manufactured toys, stuffed animals, and siblings, was my happy place of solace and unfettered imagination. I was left alone. I did have paper and crayons. I had a window that brought the blackness of night into my room. And I had a private party with the stars and the moon. I also imagined myself with Zorro, the Disney Mexican outlaw hero, who came out of the night (into my South Central Los Angeles colored people neighborhood) on his black horse to punish the greedy and wicked and to take me away! As I grew and left childhood, became a wife, parent, and then single, the bedroom became a place for hard sleeping or studying late at night.

In 2020 my bed became my everything.

For five years I had worked hard as a multidisciplinary social justice artist, wrote, produced and performed two plays, attended theological seminary and obtained a masters degree in religious leadership, had two installations at the Weisman Art Museum, and had begun to build YO MAMA’S House Cooperative. I was weary and looking forward to retiring and replenishing myself for the remainder of the year. I had moved so much in my life that I recognized that lifelong losses and sadness, now grief and sorrow, were lying beneath a sheer veneer of coping. Then COVID took the world hostage.

My oldest daughter met me at the door on March 13, 2020, and laid down the law for our household. She was in charge. She was ready to assume the responsibility of taking care of me, her aging, at-risk mother… What? Really? She had made arrangements to add the youngest grandchild to the fold. She had a strategic plan to shelter, feed, and protect us. We were to keep a rigid social distance practice by staying home. Alone. Just us. She had an arsenal of cleaning supplies, hand sanitizers, and masks. Paper and cloth. Later she ordered elaborate African fabric and produced over 100 handsewn masks. (This helped her anxiety.) These were distributed to anybody who came to our door. Nobody was allowed into our home without one. She had ordered emergency supplies, food, seeds for planting a garden, toilet paper, a bullhorn, and a machete for each of us. She ended her long-winded sermon with, “YOU ARE NOT GOING TO PLAY BINGO!” I had no words. I knew she was scared. I knew she was protecting her family. She stood before me like Harriet Tubman. We were standing at the crossroads of survival. It was the “by any means necessary” moment of our lives. I said nothing. I was to quarantine to keep myself safe—us safe. I would not be the one to bring in the Trojan Horse.

I had no problem with that.

I hadn’t given much thought to the coronavirus before March. There is a lot of distance between China and Minnesota. The initial information was so meager I could dismiss it. But I was exhausted and welcomed this STAYCAY. Well, sort of. I loved being with my family. It was fun to watch movies together, discover the world through the eyes of a nine-year-old, who talked a blue streak about what she watched on TV: Kipo, Black Lightning, Nailed It!, kittens and TikTok videos. There were moments when my daughter had to mediate an intergenerational conflict about the use and importance of social media between us.

We all snacked on whatever our taste buds dictated. We were gifted meal boxes and cooked elaborate meals with exotic spices. Friends brought plates and bowls from their kitchens. We ate what our backyard garden grew. We tested the norms of daily living, from keeping a daily schedule to how long we’d been wearing the same clothes. One day I made a conscious decision to hang my bra on the bathroom doorknob. Was I rebelling? It hung there for two days. I picked it up and put it back on.

Then the days became long.

I’d stand at the living room window and watch for long stretches of time. Most of the people I saw continued to live business as usual. There were parades of unmasked people moving around. My mind entertained them joining the ranks of The Walking Dead. I remembered movies like 28 Days Later, End of Days, and others. I tried to give careful thought to the apocalypse. Were we at WHEN HELL FROZE OVER or in THE MEANWHILE?

In May, George Floyd was murdered. The Revolution was televised. A 17-year-old black girl filmed this horror on her cellphone and shared it on social media. The world engaged in its rage.

We live in North Minneapolis. This community had preexisting vulnerabilities and disparities long before the city began to burn and unravel. My triple Aries daughter ignited her own fires of resistance.

We went into survival mode. We heard gunshots. We saw white men in trucks pull in and peel out into the driveway ravines of the Hall School directly across from our fourplex. A woman, kidnapped, is found murdered in a car, raped, by our backyard fence. This heinous act sparks conversion and solidarity with our neighbors.

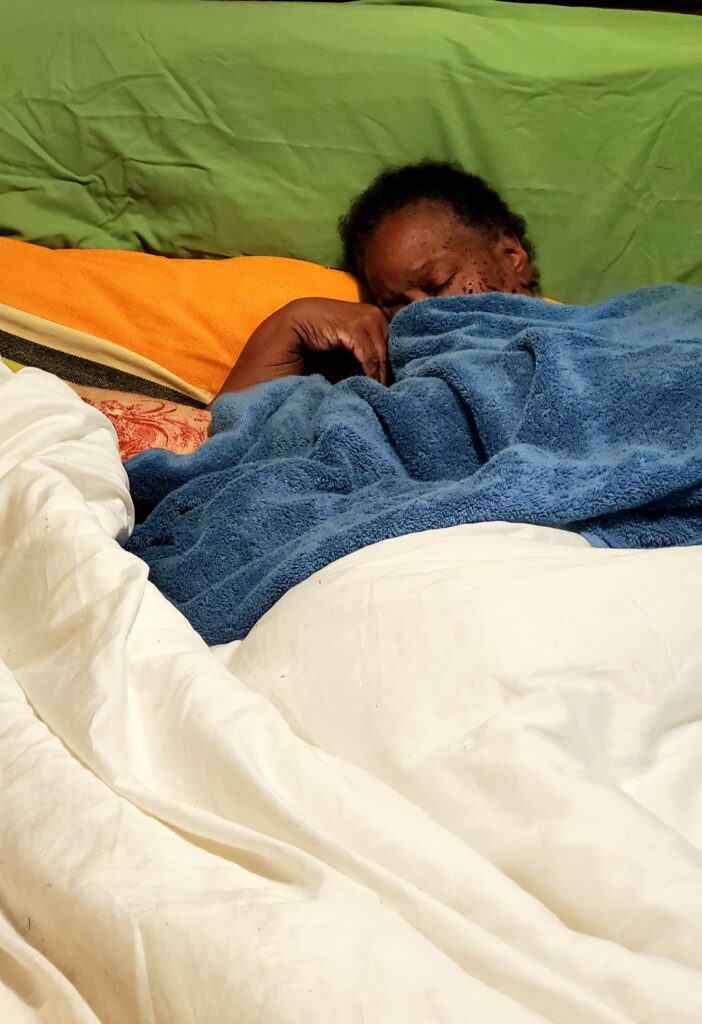

My daughter stayed up all night and slept during the day. I stayed up all day, but catnapped during the night. I cooked. My daughter patrolled our premises. The nine-year-old made art inside protective forts made from towels, sheets, blankets, and boxes.

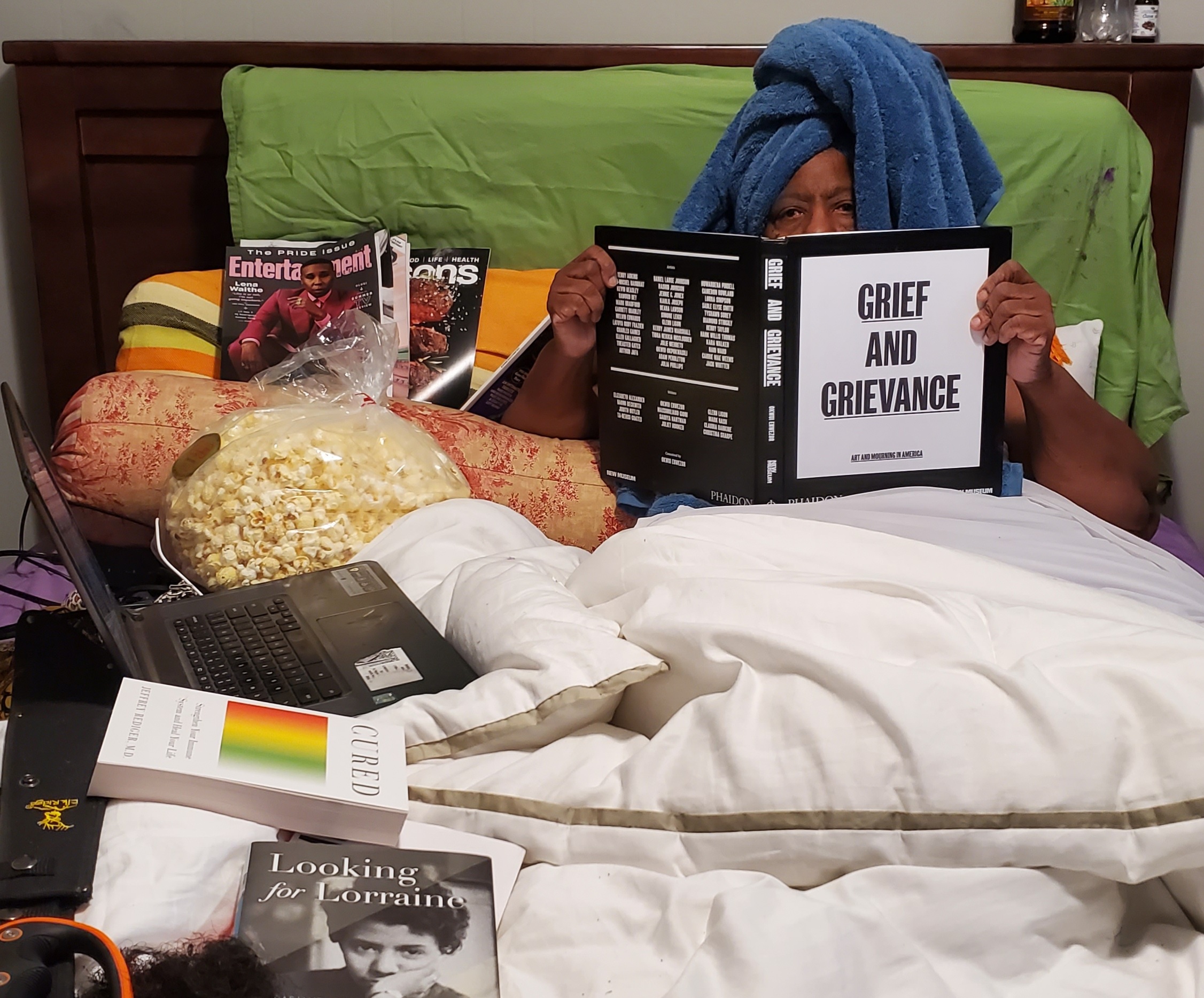

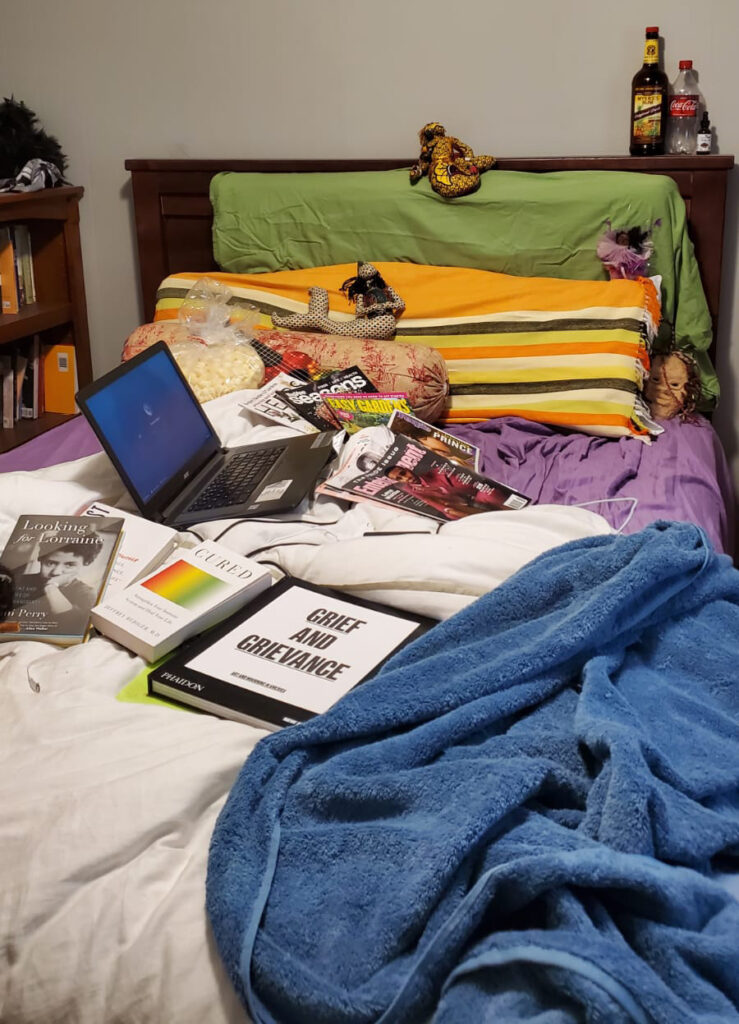

Very shortly, the three of us began to drift and find personal spaces. I began to stay more and more in my room, and then more and more in my bed. I needed the soothing touch of cotton sheets, downy thick pillows, and crisp, puffy comforters. I needed to touch the sharp edges of books, grasp pen and archive thoughts, feelings, fleeting dreams on unlined paper. I began to watch TV shows like CSI and Special Victims Unit. I needed to know more heinous human behavior than what had been revealed in Minneapolis. I was amazed this show had 18 seasons and I had never heard of it. Also, I developed a very surprising celebrity crush: BD Wong!

My bed is a sanctuary: a safe place, resting, sleeping, and vivid dreaming. In my waking state, my bed was a place for finding all things forgotten or lost. I swaddled myself unapologetically in piled pillows, the weight of blankets and a cat, clothes, books, paper, pens, dishes, snacks, bottles and cans. I stopped making the bed. I purchased comforters with Caribbean seascapes, mermaids, dolphins, and whales. I wrapped myself like a mummy in satin purple sheets.

I have many conversations with my Ancestors. I persistently ask, “Since I know that you survived some god-awful shit for hundreds of years, what do you know about this?”

Then there are serious conversations with the Creator Spirit. There are no Burning Bushes in North Minneapolis. But I burn copal that creates the circular whiteness of Ase and my intention to commune. And I talk.

I say, “I am getting old, aging in this Time of COVID. I have been told that YOU don’t give anything to a person that they can’t handle. YOU must think a whole lot about a Black Woman. ME. But WE must have a conversation about aging. Getting old. I have never felt so vulnerable. So frightened for myself, my family, community, the fate of everything living on the planet. I have always been willing to do my part and you know, but black bodies have been overburdened. YOU did NOT provide any instructions. Old or New Testament proverbs, archaeological evidence. Bones. Photos. Tweets. Snapshots! TikTok! Miracles! Warnings! Nothing!”

An example: I had put a folded one-dollar bill in my bra. Under my left tit. Later, I shoved my fingers and fished around but found no money. I can’t imagine it getting past a barrier of underwire. With sagging flesh, everything is hot, moist and sticky. Why would this paper not stick and stay? Later, going to pee, I squat and peel down my panties: George Washington is looking at me.

“Creator Spirit, is this my Second Childhood? I feel so unarmed, ignorant and lost.” I gather my harvest of collectible, comforting stuff around me. I tuck myself into soft folds and add awnings and shrouds of more bed linen and wraps. I place hard- and softcover books on my body like stones that mark a grave. There’d be no TV superhero rescue for a grown-ass black woman.

It is only in my bed that I am able to find peace. Even if it is fleeting. I am able to speak the howling unsaids of my lifetime. I can unfetter my imagination from fears. I have no idea even what to pray for. Maybe: “Detach me from the yoke of my human brokenness.”

I wait.

Your answer is a gentle, maternal whisper.

“Release.”

The tears held back by a mental paperclip, so carefully constructed, come cascading from eyes to thighs. A maniacal laughter, so anciently sinister, follows. And oh, that fart comes, with sound and mass, a smorgasbord of snacking and binging in times of the initial lockdown. Thank all the gods it is scentless, yet it fills and smothers an internal trauma-induced landfill. A mother of all farts that begins as a bubble in your guts, builds to a medley of harmonies, and ends with the Mothership concerto in the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

I am safe—but not soundless—in my bed.