MUSIC: How Do You Suppose She Got to That Moment?

Alison Morse offers a lyrical profile of internationally acclaimed composer Mary Ellen Childs, whose movement-rich compositions weave between dance, visual art, music, and poetry.

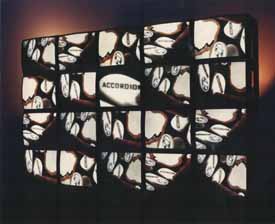

WHEN MINNESOTA COMPOSER MARY ELLEN CHILDS winner of prestigious national awards and commissionsagrees to an interview with me, she suggests we meet at her home. What kind of home would this accomplished classical composer live in? A sleek, modern box reflective of the clean precision of her music? Would the décor evince a mix of styles that would speak to the diversity of instrumentseverything from accordion to handsthat inspire her? To be honest, Im nervous approaching her at all, much less in her home. After all, arent classical composers supposed to be unapproachable geniuses?

When I get there, Mary Ellen Childs’s home looks like all the other houses on her blockat least from the outside. She greets me at the door, a slight woman with hazel eyes, a musical voice and the graceful gestures of a dancer. Escorting me past her unassuming first-floor living space, she leads me up to the second floor: a high-ceilinged, light-filled studio with white walls and a bank of windows. Modern, yes, but light and airy too. She offers me a glass of water and curls up in a chair.

I never thought I could be a composer, Mary Ellen confesses, immediately dispelling my trepidation with her candor and accessibility. I thought composers were geniuses who channeled whole operas at one time. But choreography was a different story. Growing up in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, ballet classes were as much a part of her life as flute and piano lessons; she put together shows in her grandmas basement and choreographed her high schools musicals. A favorite childhood pastime involved studying photos of dancers in performance, wondering: how do you suppose they got to that moment?

_________________________________________________

“I never thought I would be a composer,” Mary Ellen confesses. I thought composers were geniuses who channeled whole operas at one time.

_________________________________________________

Entering college as a math major, she shied away from music composition classes until her last year as an undergraduate. Only then did she decide to pursue a Masters Degree in Music Composition. But traditional composition classes, where she drew notes on music paper then received teacher comments afterward, didnt satisfy. She found her interests circling back to movement. She sat in on dance rehearsals, which, she says, provided her with composition lessons in real time. Choreographers manipulated dancers to refine their movements right in front of her; it was an immediate, physical approach to the creative process that inspired the choreographer dwelling in Childs, the composer. Shes composed both wayson paper and in rehearsalever since. In fact, as Mary Ellen talks about her past, I notice that her studio desk and chair are on wheels. She explains that the furniture needs to be easily moved, to increase floor space during rehearsals. For this composer, movement truly is key.

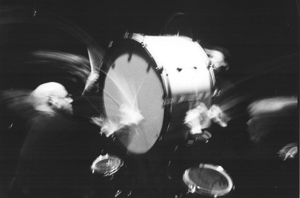

Childs began working with percussionists because she liked the way they moved. Click, Childss breakout percussion piece, started with one percussionist (Peter OGorman), two dancers and no score. I made it up as I went along, says Mary Ellen, composing it in rehearsal, taking into consideration how the performers moved, the audiences experience, and what the performers themselves could imagine. One year and forty rehearsals later, she created what she calls visual percussion, which predates other dance-percussion pieces like Stomp by a few years.

As a percussionist, says OGorman, during a phone conversation about Childs, you move to create the most beautiful sound you can, but Childss approach is more expansive. He is now a member of Childss percussion ensemble, Crash. Heather Barringer, another member of Crash who I interview by phone, says Childs may come to rehearsal with one gesturesay, a sweeping motion. The performers then proceed to sweep, swoosh, bang, turn, hit things. If Mary Ellen hears or sees something she likes, she adds it to the composition.

This is a risky way to work. Of course, it is anxiety-producing to be on the spot, says Childs. She was terrified for years, she admits, but going into a new area of your life or your thinking, if youre not scared, youre missing out. Theres a lot of richness.

True to form, she is constantly moving her work into new areas, sometimes literally. Barringer recalls one impromptu Crash performance at the Woodbury Fair, on a ride called Tempest in a Teacup. Childs videotaped the percussionists as they performed on sticks while spinning around in the cup-shaped seatsuntil the ride kicked into high gear, at which point the instruments and video-camera flew into the crowd while the ensemble clung to their teacups. Heather may never follow Mary Ellen onto an amusement park ride again, but she continues to follow her just about anywhere else. International audiences, too, continue to be delighted by Childss new ideas. I always try to create an element of surprise for the audience, she says, and for herself.

_________________________________________________

Childs videotaped the percussionists as they performed on sticks while spinning around in the ride’s cup-shaped seatsuntil “Tempest in a Teacup” kicked into high gear, at which point the instruments and video-camera flew into the crowd while the ensemble clung to their teacups.

_________________________________________________

Looking for change and inspired by the diversity of New York, Childs moved there in the early ’90s; she continued to work extensively in the Twin Cities, commuting back and forth, until one morning when she woke up in St Paul and didnt remember where I was. It was at that point, she says, that she realized Minnesota was her home. She bought a house in Minneapolis (the site of our interview), which inspired her multimedia work, Dream House, a meditation on cycles of time and the rhythms of construction work. Movement is certainly a spiritual issue for Childs. She practices Kundalini yoga and says that its philosophy played a big role in Dream House and in her newest project, an opera. Me? An opera? she thought, when Nautilus Music Theater approached her with the project. Again, for this new endeavor, she drew inspiration from movement, this time she was sparked by the idea of flight. I want to stay in the world, moving into new areas, says Childs, when asked about the future. The opera is one new challenge. She also hopes to collaborate with a director on a feature film score.

At the close of our interview, I notice three bicycle-like instruments standing against one of the studio walls. Childs commissioned them from sculptor Norman Andersen. She urges me to get on the pipecercycle. As soon as I start pedaling, the organ pipes attached to the stationary bike toot like foghorns. Here I am, in Mary Ellen Childss approachable dream house, moving to make music. To my delight, she has even managed to choreograph me into the dance that is her lifes work.

About the author: Alison Morses poetry and prose has been published in Water~Stone, Rhino, The Potomac and a bunch of other places. She is currently spit-polishing a novel, The Beethoven Frieze, about animators during Yugoslavias collapse. For twenty years she animated everything from cigarettes and glass shards to Barbie in 3D computer models and taught at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and the University of Minnesota. Now she runs TalkingImageConnection, an organization that brings together writers, contemporary visual artists and new audiences.

The next TalkingImageConnection reading, on October 11th, is the result of a year-long collaboration between sculptor-woodworker Seth Keller and six writers at the 332 Gallery in the Northrup King Building. For more information, check the calendar on www.talkimage.org.