Multiple Personalities in Order: “Camille” at Old Arizona

Elizabeth Millard finds the collaborative approach of this drama recounting Camille Claudel's troubled life to be rich and effective. The play runs through November 19.

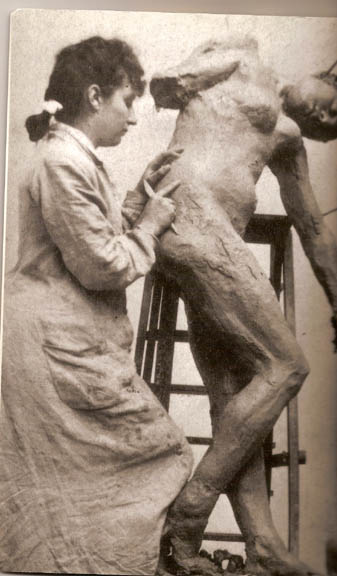

Old Arizona’s production of “Camille,” portraying the turbulent life of sculptor Camille Claudel, doesn’t have a single piece of sculpture in the props list, but creates a notable work of art anyway.

Directed and co-produced by recent Minnesota transplant Genevieve Bennett — who here displays her first non-New-York work — the production is distinctive in part for its fluid movement. The five actors, who all play Claudel at different points in the sculptor’s life as well as other characters, circle and surround each other frequently. In one scene, they become living embodiments of Claudel’s art, draping arms across one another, flowing across the bodies of the other Camilles, to give the production a cohesive feel.

The spare set (by Anna Lawence) is comprised of four boxes, each smaller than the last, in a nod toward the increasingly dwindling world that Claudel experienced. In her youth, she is dwarfed by the large space, but as she grows older and finally into madness, Claudel can barely stand, squeezed on all sides by a world that has compacted her thoughts inward and literally bends her in half.

As a young Claudel, Mirna Rae artfully captures the artist’s juvenile combination of hope and fledgling arrogance. Bright-eyed, with chin confidently raised, this first Camille emerges from her ample box with a steady stride and high voice, before goading her brother into posing for her first sculptures.

Appreciated by a Parisian teacher, she’s bundled off to the City of Lights and emerges a bit more hesitantly from her next boxy world. This Camille is played by Jaime Kleiman. As a woman appreciated, loved, then scorned, Kleiman has the difficult task of portraying Claudel through her largest range of emotion and experience, and she succeeds quite well. Hers is a trembling Claudel, both from romantic and artistic passion. The tremor is also fueled by a nascent outrage that will ultimately consume her.

Older, somewhat wiser, the Claudel taken on by Sara Richardson is often a tangle of confusion, and Richardson is sublime in the way she works to retain the character’s dignity in an arena of constant media criticism.

A particularly intriguing decision is to have Rodin set at a distance, although his actions play a central role Claudel’s life. Rather than have any of the actors play Rodin, as they do with other characters, the sculptor is tangential, with his words drawn from letters that are spoken by all the actors as a chorus.

This sense of remove heightens Rodin’s inaccessibility, even when he’s pronouncing his unquenchable love and passion for Claudel. At first, the sculptress is charmed by his attentions and even becomes somewhat haughty to her dear friend, driving her away with snippy comments and an increasing aura of self-importance.

But as the relationship with Rodin sours, and the critics begin dismissing her work as a mere shadow of his, Claudel’s frustration turns obsessive. Slipping into the role of madwoman-in-the-attic, Judith Howard emerges from the smallest box with hair in disarray and mind to match. Unlike the other actors who struggle with restraint, Howard has no such directive, and seems to relish the scene in which she destroys Claudel’s studio, screaming and writhing on the floor.

Absent any more worlds-as-boxes, Claudel is finally institutionalized, portrayed by the majestic Lavina Erickson as a confused, twitching shell of her former self, but still with a flickering recognition of her unappreciated talent. She drifts in and out of self-consciousness, as the younger Claudels appear before her, a reminder of a life that could have been lived differently.

That the actors are so precise and exquisite in their roles isn’t a surprise, given the collaborative nature of the production. Although Bennett was the one who initially stumbled on Claudel’s story while researching Rodin, she involved the five actors in creating the story. The group pieced together letters, journals, medical records, reports from the Ministry of Fine Arts in Paris, and even read Ibsen’s “When We Dead Awaken” for a sense of tone. The result is a unique experience: we hear Claudel’s own words interpreted with sensitivity and, at times, sly wit.

Camille runs November 17-19 at the Old Arizona Theater, 2821 Nicollet Ave. S., Mpls. Call 612-871-0050 for tickets.