Mother’s Egg Pie (Now, with Cardamom)

Baking with interdisciplinary artist and Black feminist scholar Tia-Simone Gardner: on cross-generational landscapes and the process of iteration

When Tia-Simone Gardner was growing up in Fairfield, Alabama, a small steel town near the much larger city of Birmingham, she lived in the house her grandparents built. But her grandma, Verna Walker, died before Tia was born.

Living in her grandmother’s home was an intimate thing. The curtains she sewed were still hanging in the windows, the flowers she grew in the garden continued to do so. Tia’s mother and aunties cooked her grandmother’s recipes. And when Tia would ask about what her grandmother was like, she found that the easiest answers came when her questions were sideways: what did the rooms in the house used to look like? What did they smell like? What kinds of trees grew out front? Pecan trees, for one. Tia’s mother and auntie still make the nut pies inspired by those trees.

“I don’t have access to my own memories, but being able to access them through other people’s memories feels like a nice way to get to know her.”

As an interdisciplinary artist working primarily with photography, moving image, and drawing, at one point Tia’s practice shifted to breaking things, and then making that thing act like another. How could she make a drawing act like a photo, for instance, or vice versa? When she started looking for examples, she had trouble finding them. So she knew she had to make them. And make them again. And again.

Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

“There’s something that’s interesting to me about iteration—like, we can do things again. I think about the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. He was basically making the same building again and again and again, and that’s how you know one of his buildings. Because sometimes, you haven’t moved on yet.”

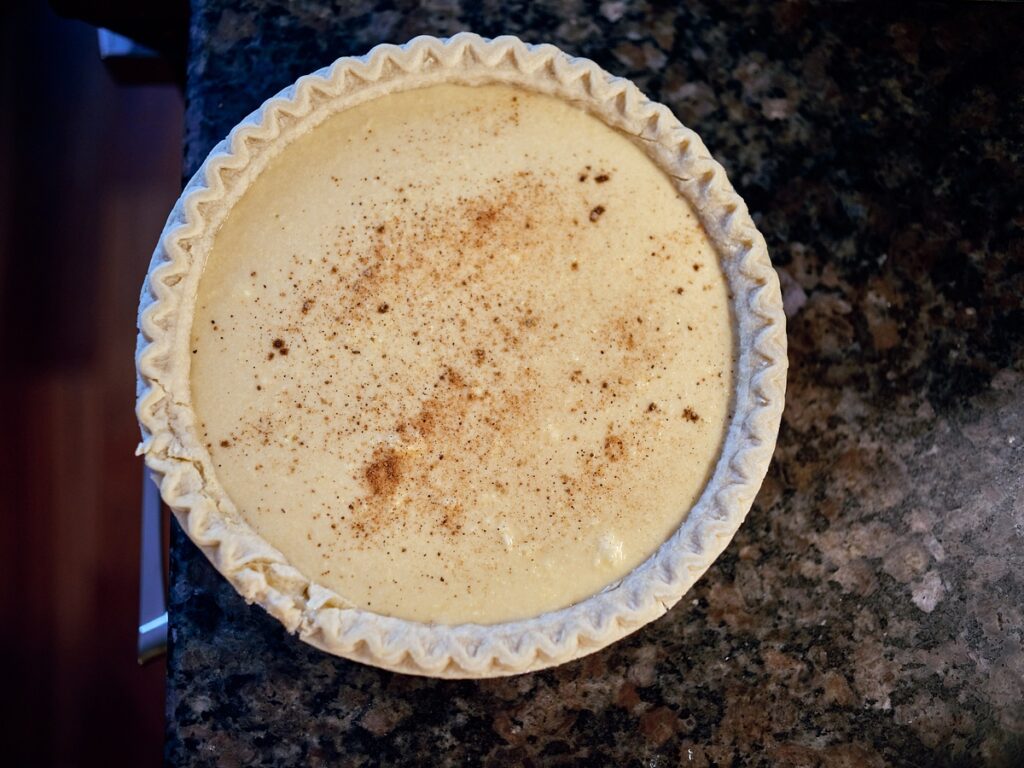

She’s arrived in my kitchen to bake her grandmother’s egg pie, beloved by her family for its resourcefulness—they may not have always had everything, but they had chickens laying eggs—and for its delicacy. You have to do it right, do it meticulously, or it won’t set properly. And then you would have to make it again.

Tia wears a white, low-plunge, V-neck sweater, a close-cropped haircut and smart glasses. She seems rooted to the space she occupies, but she fusses over the pie, unsure of whether it will set. It sets perfectly.

After moving from Alabama to New Orleans, then New York, then Minnesota, in pursuit of a career in art, Tia found herself drawn to the Mississippi river—an obvious touchstone for anyone knowing what it means to miss New Orleans. She thought of making a giant floating camera, large enough to accommodate a human being inside.

“I was thinking about these mythologies—these stories about people who could walk on water back home back to Africa, or fly, and I thought, ‘Oh! I’m gonna make something like that. It will let these objects travel down the Mississippi. I’ll be able to track them and find them. And maybe there will be caretakers for them along the way.”

But the camera turned out to be so big, and so heavy, that it had to be pulled by a tow truck. So she made it again. But this time, it was too light—so light that the sides would flap around. So then she thought she’d make it again. This time, it needed a skeleton.

“I thought, ‘This is iteration.’ You can take something to the public, let the public feel it, and then do it again. That’s okay.”

It’s a fascinating—and arguably counterintuitive—concept in any creative pursuit, with conventional wisdom expecting each new project to be not just bigger and better, but also different.

“But you are only ever seeing the hundred-thousand and ninety-seventh try or attempt at amazing, beautiful art. And then you’re like, ‘This person is a genius!’ But you see the problem—you haven’t seen all the mistakes, all the things that were in the trash, the cuts, all of it. There’s something about doing that process in public that feels different.”

When Tia’s mom and dad got married, her grandmother bought the couple their first bedroom set. When Tia became an adult, her mom bought her an expensive Kitchen Aid mixer.

“Her mom did that stuff for her, now she does it for me. Observing my aunties, I see their personalities overlap. I get some idea of my grandmother. My mom and my aunties, they’re very organized people, very meticulous about caring for people. There’s a lot of attention to detail. They’re always checking up. They all do it. They keep doing it. They’re interesting—seeing them in action gives me a whole idea of what my grandmother probably was like.”

She thinks of getting to know her grandmother, in this roundabout sense, in watching her grandmother’s daughters iterate her, as another potential body of work. Going towards touchstones, like this pie, and feeling around for what emerges. And if it doesn’t work—doing it again.

“There’s a whole thing about chicken and dumplings. My grandmother used to raise chickens, and my aunt would pop the head off the chickens. She’s maybe 4’11’’. She was always so delicate. It’s hard to imagine her doing something like that. But her mama told her to do it, so she did it. Things like that live in my brain. They had fig trees, and the neighbors had a goat.”

So the body of work that Tia is reaching for now goes deeper towards that house, and what she calls “cross-generational landscapes.”

Fairfield was a place of extreme comfort for Tia—she never knew what it was like to be the only Black person in the room, for instance.

“In Minnesota, I was once mistaken for a visiting British woman. We look nothing alike! I thought, ‘You aren’t seeing me.”

A lot of Black people lived in Fairfield after the Great Migration because it was a steel town, including Tia’s grandparents. Instead of going north, they chose to stay in the south.

“It was this amazing insular community, where I was surrounded by Black folks. Maybe folks don’t think about the south like that, but I actually had insulation from racism. It wasn’t a complete bubble, but I had a lot of folks and elders around who took care of me.”

Sabrina Fluegel and Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Mecca Bos, Sabrina Fluegel, and Tia-Simone Gardner. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

Tia-Simone Gardner and Mecca Bos. Photo: Uche Iroegbu.

And yet, there are difficult truths and frictions that come with communities like Fairfield, too. The town was actually planned and paid for by the U.S. Steel Corporation, resulting in the institutional extraction of Black labor, and the extraction of mining the earth beneath it.

Tia calls Fairfield, and her family experience there, a “Black landscape,” in her Chronotopophobias series, which includes digital photo stills from a drone flown over Fairfield. The photos reveal just that—a decidedly manmade-looking landscape, with rows of nearly identical houses in, yes, an iterative pattern. But of course each individual plot contains a unique and highly particular world—fig trees, goats, beheaded chickens. Nothing identical about it.

In an essay that accompanies Chronotopophobias, Tia quotes Yale Theater and Performance professor Tavia Nyong’o:

“In the process of recollecting the story of the past, we repeatedly lose the plot.”

Or, as Tia herself puts it in the same essay: “Sameness, though, is not sameness.”

Just because something gets done over and over again, doesn’t mean that it isn’t, in fact, different.

“I’m adding something to this pie that wasn’t in my grandma’s recipe. Cardamom. It just sounds like it could be good. We’ll see how it works out. I don’t know.”

And even if the next iteration doesn’t work out? That’s a’ight, too. “My mom is really precise, and can cook quickly. I can’t cook fast, or multiple things at once. Even if it’s just eggs, toast, and coffee, it will still take me 30 minutes to do that. But my mom and aunties? They cook fast. Her mom would do that too. I think about that a lot. It takes me forever, but they’re fast. But I’m okay with my speed. I mess stuff up if I go too quickly. I burn stuff.”

“Mother’s egg pie”

1 cup sugar (almost full) 3 teaspoons flour 1 can PET milk (evaporated milk) 3 eggs 1 teaspoon vanilla flavor Tiny pinch salt 1 tablespoon butter or margarine Cardamom extract, optional Cream butter, sugar, flour, separate eggs. (Sorry, but the bottom of the recipe got cut off and lost over the years. She dictated the recipe to me in 1975 when she came out to visit. I think you beat the egg whites a little, then mix the ingredients together and put them in a pie shell. She did say that you bake at 375 degrees.)