Mother Tongues

Lightsey Darst and Molly Sutton Kiefer (author of "Nestuary") talk about writing to the carnal complexity of women's lives, including the "shocking, commonplace, irrevocable" experiences of birth and motherhood.

Nothing is quite the same when you’re carrying a child. Insides, outsides, beginnings, descent, personhood, family, bodies, love, all lose their outlines and drift. Something that would once have been simple—the question “Do you have any children?” or a forward fold in yoga—becomes at once knotty and diffuse, an occasion for wandering. Do I have children? Yes, but I can’t show you. Or no, not yet: I have something that is not a child (though there’s nothing else it could be). My forward fold is interrupted by another person, or maybe it would be more accurate to say another will. Pull your belly in is all very well when it really is your belly and not, strangely, an inhabited landscape. Sometimes—because my child, or whatever you want to call it, is male—I’m not entirely sure what gender to call myself.

Reading doesn’t escape the oddity. I’ve always loved that lifting free from the self that literature allows—impartiality, lightness, empathy. But now I’m too acutely aware that nothing I’m doing is more important than incubating this not-yet-a-child to even leave the ground. I’m lodged in myself as he is lodged in me. More than that: I’m too strange to lodge anywhere else. I’m acutely aware of my insufferable specificity (I am this person at this moment housing this becoming-person at this moment of becoming) and also how unlikely I am to turn up in any book.

When I am addressed—when I read a book like Molly Sutton Kiefer’s Nestuary, a lyric essay concerned with the flowing thought and messy flesh of maternity—the effect is even stranger. I’m at once pulled close and repelled. I want to learn from her experience at the same time that I want to insist mine will be utterly different. My stance shifts from distanced, impartial literary reader to co-conspirator to critical sister to gasping student in a second. I have reactions and questions—no answers.

As it happens, I know Kiefer. She and I both graduated from the University of Minnesota’s MFA program (though several years apart), and we met frequently in the Twin Cities poetry community before I moved to North Carolina in 2013. Molly still lives in Minnesota, where she writes, teaches, raises her kids, and makes things by hand. I emailed her some of my questions and, in the midst of end-of-semester grading and holidays, she graciously got back to me with the following replies.

Lightsey Darst

How did this project begin? I’m curious about the various parts of Nestuary—which is mostly first-person memoir in poetic prose, but also includes fictive, surreal voice mail messages from your doctor (“You have forty-eight hours before the roe will break” [25]), fragments of glossary (follicle defined as “adj. this seems too domestic” or, twice, as “n. a crypt; a cul-de-sac or lacuna” [28]). I’m asking, too, because before I spied “lyric essay” on the back of the book, I just assumed Nestuary was poetry: you’re a poet, and there’s been a wave of poetry about motherhood lately (on which more later), and this could easily have been published as poetry in the prose-ish manner of, say, Kristina Marie Darling. So, did you start out this thinking this was a memoir? Did it begin as poetry and get tugged over into essay somehow? How do you understand the division between essay and poetry anyway? (Now I’m thinking how genre is like gender, and how at some point in the project one learns the genre/gender of what one is producing, though the reality may not always be so simple.)

Molly Sutton Kiefer

This began as a sequence of pretty standard, left-justified, image-heavy personal poems. It was part of my thesis, which was meant to tell the same story, but in verse as opposed to this strange-voiced prose-thing. I was in the middle of my Loft mentorship, reading people like Jenny Boully, when I decided I really wanted to write something like Opal C. McCarthy’s Surge: An Oral Poetics and Christine Hume’s Ventifacts. These pieces that existed between genres, these indefinable, honest pieces that paid homage to poetry but weren’t that. Were something other. As the body becomes something other while occupied.

Lightsey Darst

Speaking of the body, I’m struck by your willingness to represent a gross body in print—to say, for example, that “PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome] gives you a barrel quality, abdominal drum. Waddling before the product” (15), or, in a section on birth experiences, to propose the option “Please place the creature on my chest. Please let the broth of me slick away” (53). These images run so contrary to the image cultivated by a lot of female poets—a delicate, wasting persona that we perhaps derive from Emily Dickinson. Was it difficult to put yourself out there this way?

Molly Sutton Kiefer

Absolutely not. I used to feel a bit squeamish at the idea of nudity, even when I was pre-PCOS svelte, but when I became pregnant, I began to love nakedness, even in all its flaccid, stretched glory. I think I might have made some people uncomfortable, but that’s OK by me. Art is supposed to get you moving around in your own body, thinking and being grateful—for what you haven’t had, for what you’ve had and others have too, for making it through.

But the thing is, I’ve only just recently, since the Loft mentorship, started to think about consequences of writing true events into my work when the true events aren’t just about me. As in, how will my daughter, my son feel as they grow older? My mother, she’s put up with a great deal with her characterization in my work, which I try to temper, because it’s a bit unfair—all of her angry bits are getting displayed when there is more depth, more to it, but the way it functions within the larger narrative ends up fairly stuck. I grew up in a family that essentially taught me authors use these events, their life stories, as fodder for their art. So, while I might be awkward and shy if you met me in person, I’m certainly happy to use that body, stripped away, for the writing. It feels absolutely fine and different to do it in this way. I don’t know if I’m making sense. I just know it’s like a door opening for me, and I don’t mind, nor do I want to shy away from the honest portrayal.

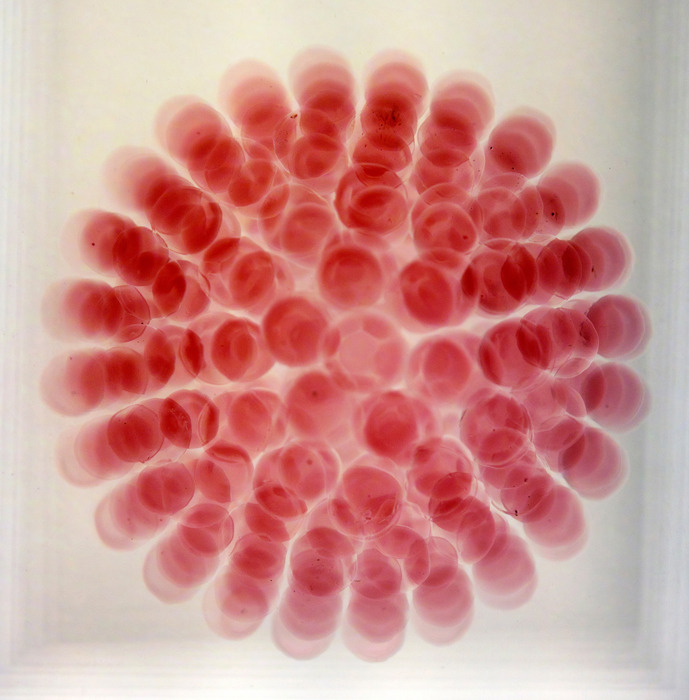

Russell Prather, Pink Pod (front view), acrylic on Dura-Lar. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

Lightsey Darst

I’ll admit I cringed more than once reading Nestuary—“Oh, I don’t know if you should write that!” I would hear some little voice in the back of my mind exclaim. When I looked into my reaction, it had to do with your subject matter, with how a narrative about pregnancy necessarily turns the family inside out. Sex, birth, infant preferences—almost by definition, “good taste” precludes the specificity you bring to these topics. For example, according to the rules of good taste, you can write about sex, but you can’t expose the occasional dutiful sex in a good relationship, particularly not dutiful procreative sex; you can write about birth, but only using imagery instead of real details and preferably leaving the baby himself/herself anonymous. Good taste dictates the biological center of the family must be viewed through gauze, set behind a scrim. . . and that means “mother” is an awkward—maybe even a forbidden—stance to write from. Mother knows everyone’s secrets; because of that, mother has to be silent. Did you feel this societal pressure? What do you think of it? Were there any rules you followed about what you could and couldn’t write?

Molly Sutton Kiefer

My poor, patient, kind, loveable husband. And sex in poetry. I got really lucky there. He knew I wanted to write when he met me over fifteen years ago, and we were such puppies then. I think, I get the impression, that he’s actually proud of my career as a writer, and he’s always pleased when I’m doing something that is constructive and makes me happy. (By constructive, I should say, what I mean is, you know, the days I’m not overspending in bookstores or indulging in something damaging to my health.)

This particular book was awkward; so often I’d re-read it and think, “My mother-in-law is going to read this.” But they’re the same, that way, my husband and mother-in-law. They handle things with grace and patience. My husband has a pretty wide limit to what he’ll tolerate from people he loves, and he knows that I don’t mention these truths without realizing the balance of it: is it worth revealing these honesties with the sacrifice of telling the truth?

As I am writing the responses to these interview questions, my nearly-four-year-old is at my feet, leaning on a stool, scribbling her wonky version of “writing.” She’ll tell me which words she wrote and will be so puffy-chested proud. And she’ll be exactly right. It makes her feel good.

I’m also very terrible at keeping my own secrets, and when my husband asked me to keep our “trying” a secret, I had to write about it over and over and over. I suppose there’s something about pent-up releases in poetry too. And lyric essays. Whatever Nestuary happens to be.

Lightsey Darst

Let’s talk about the “mommy poets,” as I’ve heard them called. You cite several—Beth Ann Fennelly, Gillian Conoley—and I can think of many more women who have written intimately about motherhood in the last ten years or so: Rachel Zucker, Arielle Greenberg, Claudia Rankine, Jessica Fisher, Julie Carr. What do you think is going on here? Is it simply that Third Wave feminists are arriving at maternity? Or is there some other cultural or literary force these writers are reacting to?

Molly Sutton Kiefer

Oh, I love the mama-poets. There’s a special place in my heart for them, especially the Poet-Moms (a listserv Arielle Greenberg runs) variety. I read a book called The Grand Permission: New Writings on Poetics and Motherhood. It’s one of the few books that I have been very good about savoring; the margins are destroyed with my writing, and I’d just tote it around like a little blankie. It gave me so many layers of confidence.

I wish I could speak out in a smart way about this particular issue. I’m such a confounded feminist that I stumble all over my flappy feet all the time. But I do think that birth and maternity are experiences that are shocking, commonplace, irrevocable. And they belong as a serious part of the canon. I wish I could understand more of the context, but I feel so deeply inside of it that it’s hard to look at the broader picture.

Lightsey Darst

Related question: Is there a poetics of maternity—a style, a certain set of answers to poetic problems—that mother-poets have adopted? I’m thinking of the thickness of language and language-play in both Nestuary and Claudia Rankine’s Plot—“I lumber, eat honey, am imaginary” (29) you write, weaving what I want to call a matrix. I’m also thinking of how mothers stereotypically see the world in terms of utility, an approach that goes against the purity of “art for art’s sake.” Rachel Zucker makes almost a point of pride of this opposition in her recent book, The Pedestrians.

Molly Sutton Kiefer

Well, I think one of the biggest issues in the poetics of maternity is to avoid the trite, the greeting-card, the saccharine. This is the source of the knee-jerk no rejection, I believe. There’s an expectation that writing on motherhood will all be goopy and delicious, like an over-sugared cookie, when really, the poets I know who are tackling motherhood in poetry are brutally honest: Zucker, Greenberg, Martha Silano. It’s how I hope my own work is, too, even when it is addressing a tender moment. I hope that it’s complex and layered and never all of anything at all.

There’s a necessity for this honesty, I think. It’s so important, because it’s so familiar. I think of that Tumblr account that went around a while ago—Reasons My Child is Crying—or something like that. There was such a fascination in peering into these desperate snapshots, because they were entertaining and true. Think of how many narratives are about power—most of them, maybe all of them. What is more powerful and more humbling than being a parent? And the inequalities and the dual selves — it’s a subject riddled with tropes and opportunity.

Lightsey Darst

Would you say a little about what a friend of mine called “the birth vortex,”this maelstrom of pressures that middle class, educated, liberal women face to do maternity “right” (i.e., without medication or surgical intervention)? What work do you imagine Nestuary doing in relation to that cultural force?

Molly Sutton Kiefer

Oh, that. I fell into that vortex too. I was so charged and desperate to have the “perfect” birth. I imagined it would be one at home, maybe in the water, with women surrounding me and om’ing and candles and essential oils and all of that warm goodness. Instead, I was in a hospital bed, given in to tubes and weird things come out of every which way and still cut open.

I wanted people to perceive me as strong. I refused an epidural for 24 hours with my first. Everything went cock-eyed for different reasons, and I guess that’s a lot of what Nestuary is about: that we don’t land all the expectations. That it’s impossible to do it right. Whenever I read the poem, “Reasonable Birth Choices,” I introduce it as an adaptation of a “birth plan,” which is “fully a farce.” The audience likes that; they understand. What a loose oxymoron—the impossibility of it all fitting together. We’re so charged to have things organized; we pack our lives so tightly. Part of the reason I made some of the choices I made in my birth was because I had an audience of sorts—my parents, my best friend—and I perceived the crowd as getting restless.

So, then, Nestuary became a restless book. It became about what was inside of me, my own distraction and inability to keep things from spilling over.

A friend of mine who had a C-section with twins said something quite smart about C-sections (I’m paraphrasing here; she said it smarter): you don’t tell a person who has PTSD from being in war to just get over it and be grateful that you won the war; why should you tell a woman who had a bad birth experience that she should move on, embrace the fact that the product is such a healthy specimen? The truth is, in order to process it, we have to grieve over parts of the journey that were disruptive, that were startling and, to use a phrase that feels so very cliché, life-changing. I cannot forget the journey I went on to bring Maya (and Finn) into my life. It’s my journey, and our birth stories—those are all our own journeys.

Lightsey Darst

The birth story is a secret genre one becomes aware of only as one approaches one’s own birth story; birth stories are told only to other mothers. (I’ve had a couple of friends more or less explicitly put off telling me their birth stories until mine’s complete.) What readership do you imagine for this book?

Molly Sutton Kiefer

Oh, I know! If I find out someone wants to give a copy to his or her pregnant friend, I say, “Oh dear, maybe wait until after.” But that’s ridiculous.

I don’t imagine a specific readership for this book. One could say mothers, but that’s limiting. I read plenty of books about experiences that are not my own, but if the writing works, then I am transported and compelled. I’ve read plenty of narratives of war, of bad marriage, of living in distant lands. And these aren’t my stories; they aren’t my journeys. I remember when I first read The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down and was blown away by the writing: it was the first time I realized how a book can be about so many things, but if the author is good, then you are in good hands. I’m not saying by any means that Nestuary is one of those books—I can only hope it might be for some people.

Lightsey Darst is a writer, critic, and teacher based in Durham, NC.