More Non-Fiction Reviews – June 2005

"The Men Who Stare At Goats," by Jon Ronson; "Ghosting: A Double Life," by Jennie Erdahl; and "Freakonomics, A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything" by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner.

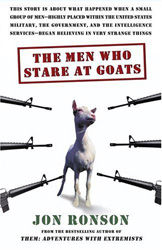

The Men Who Stare At Goats

By Jon Ronson

Simon and Schuster, $24.00

Stand-up comic David Cross frequently cracks me up; my favorite bit may be this single line about a bar fight, in which a good ol’ boy threatens that “I know 37 ways to kill you with a pimiento, my man.”

Maybe this explains why Jon Ronson’s new book, The Men Who Stare At Goats, almost immediately found its way onto my “books to reread as soon as I finish them” pile. While stopping short of pepper-based warfare, it details the U.S. Army’s experiments with just about every other bizarre possibility—from “psychoelectronic” weapons (like, er, the Barney theme song) and psychic spying to top-secret programs aimed at teaching soldiers how to walk through walls, become invisible and kill through sheer force of will. And the best, worst, scariest and funniest part about it: it’s all true.

Or as true as some of this stuff can be, anyway—it’s hard to know whether to believe famed 1970s spoon-bender Uri Geller when he not only claims that he was a psychic spy for the CIA, but implies that he’s returned to the agency to help with the War on Terror. But Ronson, also a filmmaker and the author of the funnier-than-it-had-any-right-to-be Them: Adventures With Extremists, has a knack for ferreting out the bizarre-but-verifiable, and the undeniable stuff here is just as mind-boggling as Geller’s feats of cutlery modification. Most of the ideas he details stem from the First Earth Battalion, a non-lethal, peace-and-love-oriented military unit proposed by Jim Channon. Channon was a Vietnam-era lieutenant colonel who, in the wake of that war’s atrocities (and his own discovery that very few soldiers actually wanted to kill anyone), envisioned the First Earth Battalion as a way of turning soldiers into peace-loving “Warrior Monks,” ascetic vegetarians who carried flowers into war zones but also possessed the ability to control the enemy’s thoughts.

Preposterous? Maybe. But for the last thirty years and counting, the U.S. Armed Forces have been working to implement portions of Channon’s ideas (granted, usually with more lethal modifications). Sometimes they’ve failed—reputedly, only one man ever actually stared a goat to death—and sometimes they’ve been all too successful. Indeed, many of Ronson’s interview subjects believe that the photos of the torture at Abu Ghraib, far from being inadvertent leaks, were actually the whole point, a demoralizing psy-ops ploy stemming from First Earth’s initially benign ideas about information control.

And that’s what really makes this investigation so interesting—Ronson’s visits with many of the principals are downright hilarious, but his willingness to explore the dark side of these experiments lends gravitas to the comedy. The story of an innocent detainee at Guantanamo being “tortured” by inoffensive music played at regular volume, for example, is strange and funny, but also raises questions about just what the hell else might be going on behind those impenetrable walls. The chapter on Erik Olson, son of a CIA-affiliated chemist who died mysteriously while working on the infamous MK-Ultra project (which researched the possibility of mind control through LSD) is both poignant and kind of terrifying.

Thus, while a number of the accounts here are ludicrous, by the end of the book it’s the weird menace lurking behind these secret operations that sticks with you. So when Ronson casually mentions that the Bush administration’s budget for Black Ops—top secret, unidentified military and intelligence research—is the highest it’s been since the Cold War-era development of the stealth bomber, the question of where it’s going will very likely keep you up nights.

‘Cause I really doubt they’re buying $23 billion worth of pimientos. —Matt Konrad

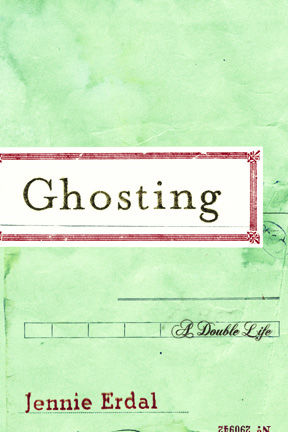

Ghosting:

A Double Life

By Jennie Erdahl

Doubleday, $24.00

Ghosting is a charming, forthright first-person account of one woman’s 15 years as ghostwriter for a well-regarded London publisher-turned-author, “Tiger.” References to British literati, including the pseudonymous publisher, will be meaningless to a great many American readers, but Erdahl’s deft wit and engaging accounts of the idiosyncracies of the British literary scene and her eccentric boss’s increasingly farcical demands are colorful enough to draw in readers of any background. There’s plenty of gossipy inside information about the ghostwriting trade and the often silly, preening world of publishing. But Erdahl’s account transcends mere dish. Reflecting on her own willingness to serve, uncredited, as another’s voice she offers unexpected insight into the burden of bearing one’s own identity and the illicit thrill of shedding it. Erdahl wasn’t overwhelmed or exploited by Tiger; she colluded with him, an active participant in the charade (at least for a while), penning two novels, some nonfiction, and a slew of newspaper columns for print under his name. Theirs was a symbiotic arrangement. If you’re inclined toward the “writers on writing” memoirs, you’ll love Erdahl’s delicately witty, humane account of this little-remarked upon branch of letters. —Susannah McNeely

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

By Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner

William Morrow, $25.95

Maverick economist Steven Levitt isn’t interested in global markets or the dot-com bubble or interest rate hikes—debunking common wisdom is his game and, unfettered by dogma or political correctness, Levitt uses his econ-theory toolbox to romp through the whys and wherefores of everyday life in modern America. Why, in spite of a chorus of crime expert forecasting to the contrary, did crime rates across the country fall dramatically in the last 15 years; and where did all the criminals go? Can parents boost the performance of their kids in adulthood by reading to them and getting them into good schools? To what extent does money actually determine the outcome of political elections? If the illicit drug business is booming, how come so many crack dealers live with their mothers?

Turning his economist’s eye toward deconstructing the human incentives and costs behind behavior, Levitt gleefully shreds commonly-held preconceptions and “expert” opinions alike; his research into the available data behind these everyday riddles yields answers startling enough to topple sacred cows on both sides of the aisle and offend many more comfortable with their “givens.” Informative, provocative and relentlessly rational, Freakonomics offers a startling and revealing second look at things you’ve never thought to see before. —Susannah McNeely