Momentum: New Dance Works

Karen Sherman and Leah Nelson/Abstraktions perform in this annual showcase of the best of Twin Cities dance, at the Southern Theater through July 23. Lightsey Darst finds them rich though oddly paired.

The Momentum series continues next weekend, July 28-30, with Live Action Set with the Spaghetti Western String Company in “The Percussionist” and the BodyCartography Project in “Holiday House.”

Karen Sherman: Tiny Town

Karen Sherman’s Tiny Town is less about any real small town than about the “a small-town feel” that white Americans and particularly Midwesterners seem to cultivate, whatever the size of their towns. You know what I mean—that insidious meaningless creepy friendliness, that bland assumption of sameness, that gives pure strangers the right to ask (as Sherman’s soundtrack does) “do you love Jesus? do you love baseball?”—and of course the answer to both is supposed to be yes with a smile, because why wouldn’t you like what everyone else likes? Shut up and eat your pancakes! Sherman has applied all her considerable wit and intelligence, as well as the invention of her collaborator-dancers, costumer (the marvelous Angie Vo), designers (Jeff Bartlett for lighting, Kristin Abhalter for set), and builder (2005 MCAD/Jerome winner Kirk McCall) to this soulless culture, and the result is a stunning satiric collage.

Consider the details: Sunday afternoon sound effects rendered on stage—cordless drills, leaf blowers; a giant pile of pancakes onto which a dancer sprawls; a fake-friendly Walmart vest (“Ask me how I can help”) on an unsmiling dancer—and is the red-white-and-blue, vaguely patriotic pattern of her pants composed of tiny Budweiser labels? A backdrop of rolling green hills features a nuclear plant with a puffy gray cloud overhead; two engineer-types (Joanna Furnans and Marcus Young) haul up the puffy cloud and send it through a paper shredder. What global warming? Later the engineers fill a beer hat with O’Doul’s; the townies (Sherman, Megan Mayer, Morgan Thorson, and Kristin Van Loon) lap it up. Mayer, in a dress dotted with bright paper flowers, erects cardboard picket fences and pops open a mailbox spring-loaded with fake flowers. Later, minus her smile, she waits beside the mailbox, whispering at it and trying to smile; a fit of shivering ennui overtakes her and she hides behind a Technicolor pull-down of the St. Louis Gateway Arch.

This last mood, the I-can’t-take-this-smiley-business-anymore mood, hangs over the performance and, alas, casts a pall over it. No doubt this is intentional: Sherman shows us not rebels but stifled people who don’t even know they’re not happy. To this end the dance is a mix of sharp, scissoring moves, stiff poses, and falls into exhaustion; what seems like a fight scene between townie Thorson and the engineers, with pumped up music and threatening lighting, never quite gets off the ground, probably because Thorson isn’t supposed to know she’s fighting.

Sherman succeeds at putting the mood of purposelessness across, but the disjunction between the emotion she’s showing and the wit and energy that go into showing it is so wide as to be nearly disorienting. If what’s on stage is Anytown, America, then where did Sherman herself come from, other than St Louis? There are hints: in Sherman’s initial appearance, she’s upside-down and shoulder-walking forward in a burlap jumpsuit—clearly an alien here in pancake-land. Later, in Tiny Town’s most vivid choreography, the four townies bully and attack each other, leaving finally two (Van Loon and Sherman, each equal parts wire and liquid) to wrestle and hug with the sexual charge of teenage girls. Here is some energy. And while Sherman’s free to explore small town ennui—and quite good at it—my eye longs for energy, for attachment. Where did you come from? What do you care about?

Leah Nelson/Abstraktions: Requiem for a Homegirl

Whoever schedules Momentum seems bent on putting the four pieces together in such a way that the pairs cast unflattering illumination on each other; I’ve seen it three years running now. Where Tiny Town is colorless mass-culture (read: white), Requiem for a Homegirl is sharply colorful (read: concerned with racial politics, particularly along black-white lines); where Tiny Town is all wit and satire, Requiem for a Homegirl is painfully heartfelt. This isn’t to say that Requiem soars where Tiny Town shrinks—the damage is mutual.

The two pieces share postmodern craft: both exploit lighting (at one point Jeff Bartlett creates a dark room with light spilling through venetian blinds and car headlights roaming across the walls), costumes (by Nelson and Heather Wilson), and props (a stretch of white silk becomes a harness/wings in one haunting section); both develop by vignettes spliced together rather than by narrative. Both Sherman and Nelson have honed this craft. Nelson also has an astonishing sense for the viewer’s eye: you won’t miss a detail, because your gaze is part of what she choreographs, leading you to see now the lit-up outline of Africa on the floor, now the blooming shape of one dancer.

It’s not just that Nelson choreographs with where you’re looking in mind; she also choreographs with the color of your gaze in mind. In other words, she knows the audience is mostly white and she wants to engage with that fact. A black ballet dancer (Krystle Igbo) comes gliding across the floor on her pointe shoes, looking angelic; a couple of white patrons (Tom Scott and Amy Sackett), their heads wagging with approval, follow her. The white woman grasps one end of a string of pearls wrapped around the ballerina and the pearls unwrap into a leash. The implication’s clear, and it’s aimed right at the audience.

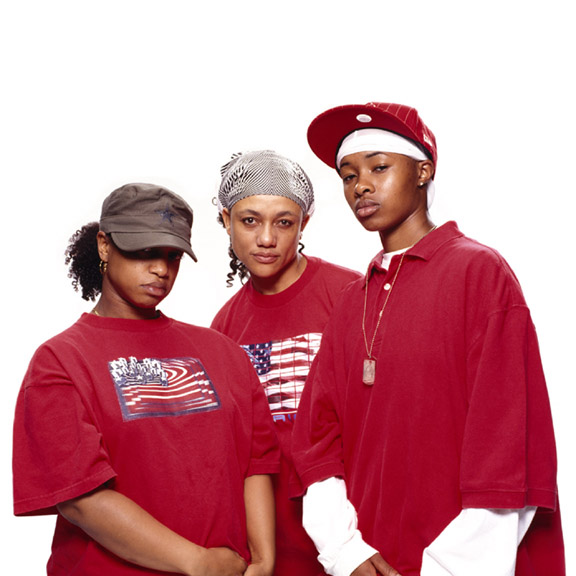

Not that Nelson’s white audience isn’t in some way armed against implications; they’re good liberals, after all, and they’re used to applauding performances that celebrate African influences and decry white racism. But Nelson lets more energy through than the audience has armed for. Dancers don hoodies and give the audience that look (you know the look: this isn’t your part of town, Becky) then explode in fierce daggering dancing. Watching this is like standing on one side of a piece of plexiglass while someone pounds at the glass from the other side. You know you won’t get hurt, but you feel a cold thrill.

When Nelson touches this edge, Requiem for a Homegirl is compelling (in both senses: there’s force involved). But often Nelson stays in more conventional territory, with a more conventional approach. Maybe she’s trying to cover too much territory (racism, history of blacks in Africa and America, urban experience), and it prevents her from going deeply into any one idea. Her metaphors become broad and fixed, her scenes unable to take wing under their metaphoric weight. A human beatbox (Carnage, aka Terrill Woods) and opera singer (Adara Bryan) perform at the same time: what we notice is not the interesting sound but the conjunction of “high” and urban culture. It’s symbolic, and then it’s over.

And then there’s the happy ending, complete with African drums and the audience clapping along (as we were earlier instructed to do). Not that I don’t sympathize with the desire to be happy or feel the energy of the drums, but where did that come from? Ten minutes before a street battle was raging; how did we—mostly black performers and mostly white audience—get to happy? Nelson wants us to come along with her to the feel-good ending, but I’m not sure what we’ve done to deserve it.

If Tiny Town and Requiem for a Homegirl don’t exactly complement each other, they’re still a demonstration of the vitality of the Twin Cities dance scene. Through their disparate modes, Sherman and Nelson both present complex, highly crafted, and individual visions; both have found excellent performers and craftspeople to help carry out their visions. Momentum? Yes, it’s here.