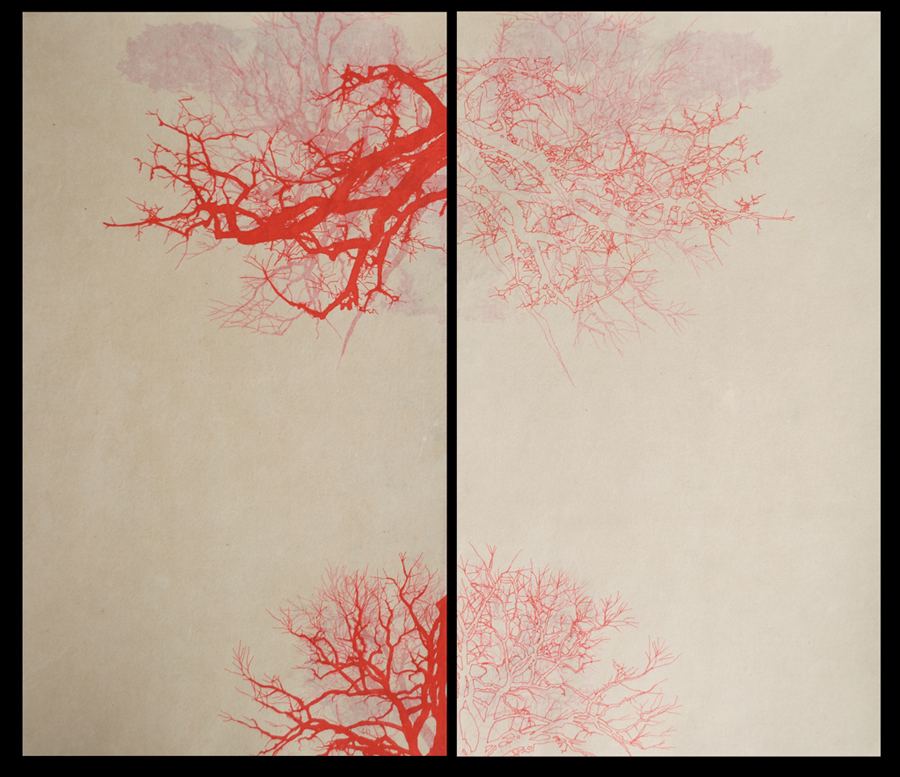

mnLIT Original: “Afterimage”

A haunting new short story by our most recent flash fiction competition grand prize-winner, Hillary Wentworth. Like all of our mnLIT Original offerings, this story is illustrated by artwork handpicked from our vast database of Minnesota artists.

IN GRADE SCHOOL SCIENCE WE PASSED AROUND A PIECE OF PAPER: a picture of a man’s face, white against a dark background. We stared at it for 30 seconds then looked away, onto a wall. There the image of Jesus appeared, dark now against the white.

Our teacher explained that looking directly into the sun could result in retinal burning — the tissue at the back of the eye actually cooking from the heat. The bright light, like Jesus’s bright face, formed an imprint on the eye that would remain long after the incident, for months or even years.

Some days at school, the air was so thick with smoke we were not allowed outside for recess. The nearby dump burned every week or so, and the smoke settled around us until we were ghosts in a playground of ash. It settled on the cemetery too, just beyond the soccer field. As children, we played a game: hold your nose while passing a graveyard, or the dead would snatch your breath and return.

Growing older, this did not seem practical. In middle school, we ran once around the soccer field for warm-ups, panting. During basketball practice, we used the cemetery loop as the team’s mile run. Our breaths couldn’t hold, and so the dead came to life:

At the school talent show — “That’s Jessie Cornwall, her mom killed herself. Shot herself in the car.”

On the bus, the smell of manure wafting through the windows — “The guy with the farmhouse down Newington Road, burned the house down while he was in it.”

At the church picnic beside Sanderson’s Pond — “A little boy drowned here some years ago, swimming to the dock.”

On the news at home, during the first Gulf War — “A plane was shot down today just after the ceasefire was called. Three men died.”

“I knew him,” my dad said, chewing the ends of his eyeglasses. “I taught him in school.”

But what about my dead? My dad’s mother, father, and brother — gone before I was born, before my parents even married. One day I cornered him in the kitchen when he was washing the dishes. “What were your parents like?” I asked. He did not look me in the eye: “Cop. Teacher. Beautiful. Strict.”

______________________________________________________

As children, we played a game: hold your nose while passing a graveyard, or the dead would snatch your breath and return.

______________________________________________________

The house where my dad and Aunt Beguine were raised, and where I grew up as well, was filled with whispers. When they drank together at the kitchen table, the smoke from their cigarettes hovered over their heads, threatening to take human form: an ear, a lip, a face. “I can hear Mom’s broom across the floorboards, scratching,” Beguine said. My dad twisted the tab of the tin can, squinted out the window at the crab apple tree.

In his twenties, my dad had claimed his brother’s dead body, an act that must have been like looking into the sun. And years later, as my dad sat at that table, the body remained, caught inside the retina. Listening to my dad and aunt down the hall, I’d look out the blackness of my small bedroom window and see it — a wisp, a streaky cloud of movement — and think there they are.

When I was 18 years old, my dad died of a heart attack. At the funeral, my mom asked if I wanted to see him, and I said no: closed casket, sealed shut, done. We placed his body in the ground, in the dirt of the same cemetery where I used to run, where I used to hold my breath. Later, my mom and brother saw my dad in dreams and in doorways. My mom said he appeared in the dust of her neglected bedroom; my brother, in swirls of beach sand. I now find myself looking into the sun and into bright objects, willing my eyes to remember, so that when I look away, he’ll be there.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Hillary Wentworth studied creative writing at the University of New Hampshire, the Salt Institute, and the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, where she received her MFA. As a 2010 grand-prize winner of the miniStories competition, her story, “146.9 Volts” was featured on mnartists.org. Her writing has also appeared in Black Warrior Review, Caesura, and the Fourth River and Twin Cities METRO magazine. She is at work on a memoir.

______________________________________________________

mnartists.org is a joint project of the Walker Art Center and the McKnight Foundation

Membership on mnartists.org is FREE. Find step-by-step instructions for how to join and how to use the free resources available on the site. If you need assistance, contact Jehra Patrick at info@mnartists.org.

The mnLIT contest for poetry and fiction is currently on hiatus. However, we are going to begin including poetry and fiction among our regular, commissioned editorial offerings; submissions of creative writing – including humor, poetry, spoken word and fiction – are also welcome for our new literary podcast, You Are Hear.

Find out about mnartists.org’s current literary programming, as well as our editorial submissions protocols here.

______________________________________________________