Mixed: “Bois Brulee” in Duluth

Julia Durst reviews the show called "Bois Brulé" at the Duluth Art Institute. It featured collaborative work by Carl Gawboy and Jay Newcomb in a union of art and craft--things that in most cultures wouldn't occupy different realms.

“Bois Brulé” refers to the French translation of an Algonquin term used to describe mixed European and Native American heritage. That’s a long description for a short exhibition name.

The name is fitting, as painter Carl Gawboy and wood fabricator Jay Newcomb both come from this mixed extraction. In fact, mixing is present through the show: sculptures with paintings, fine art with functional craft. Drawing on the Scandinavian craft of painting cutout folk figures, the men create wood cutouts painted with realistic, narrative images from Native American life. Some are wall-mounted paintings and stand-alone sculptures while others are functional objects. Paintings on canvas by Gawboy round out the show.

With so many different elements, the show feels a little uneven. The work that succeeds does so in a big way and the not-quite-there pieces fade into the periphery as space fillers, decorative and pleasant. I want art to do more than hum, though, and thankfully several of the sculptures and paintings sing.

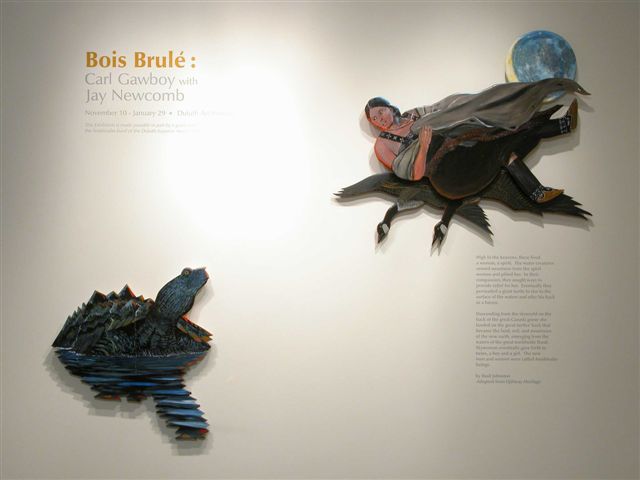

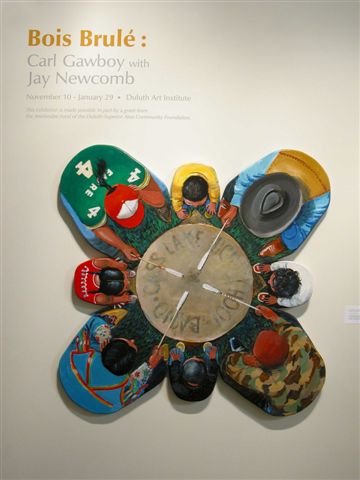

“Sky Woman and the Great Turtle” portrays an Anishinaabe story of creation in a two-piece wall-mounted work. The scene captures beautifully a climactic moment of the story in which Canada geese carry a woman to earth, where she lands on a turtle’s back. Another stunner is “Flower of the Chippewa.” It gives an overhead perspective of a Chippewa drum group and shows each of the senior drummers in a different male role: dancer, athlete, veteran and elder. The “Cass Lake” name on the drum and the Favre jersey make the piece local and contemporary, thus more resonant. Both artists are at their best in “Strawberry Moon.” Newcomb’s outline of the dusky landscape reveals the sky’s heft and warmth; Gawboy’s pockmarked moon entices touch.

The functional objects, while well-crafted and painted, are less impressive. Admittedly, this is a personal bias; I tend to prefer art that is only art and doesn’t attempt to multi-task. For instance, two headboards are painted with water scenes– one with otter and caribou, the other with an elderly couple canoeing below a brilliant orange sky. While thematically sedate, the visual complexity is just too awake for a headboard. As sentimental pieces given as gifts, they’d likely be adored and enjoyed. But not so as art.

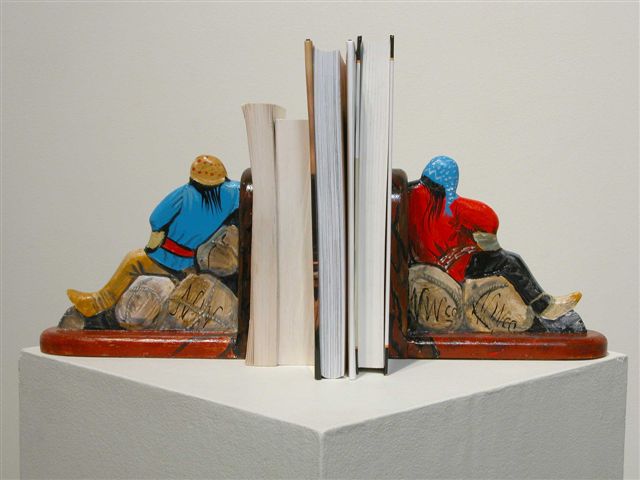

A set of bookends evokes the same response. Two voyageurs who work for the fur trade have stopped for a break and their slouch becomes a stop for the books. The wall sign explains that during their rest the men would share stories, which makes them an appropriate them for bookends. Like the headboards, there isn’t anything particularly wrong with these objects; they just don’t interest me while in the presence of grander works. A show of solely functional pieces might be interesting instead.

.

The one furniture piece that elevates itself to art is the bench, the third in a series by Gawboy and Newcomb. Gawboy’s attention to planar surfaces enables him to create the illusion of several perspectives: back and front of the canoers, above and below the water. The figures are wearing historically accurate late-19th century dress.

Gawboy’s paintings on canvas complement the collaborative work. My favorite piece in the show happens to be a painting. It alludes to the show’s theme of culture and race by tackling a darker side of history. In “Eternal Trail,” a line of weary people stretches into the horizon, representing the Trail of Tears (the government’s relocation of the Cherokee Nation to the West). The artist changes things by introducing several additional groups into the distinctly Cherokee story. He shows people from the Middle East, Africa, Southeast Asia and the Americas sharing the Cherokee’s plight of persecution.

Gawboy departs from his usual stark, bright palette for murky tones rich in moody subtleties. As a painter, he usually sticks to history (his own or that of his native culture) and seems to take pride in educating his viewer. In “Trail,” the message is emotional and moral, not factual and instructive. I hope Gawboy explores metaphoric imagery further. It provides a moving complement to his realism.

Exhibitions of culturally specific work have been a trend in the past two decades as more galleries have shown minority artists who deal directly with issues of race and culture. Kara Walker, Adrien Piper, Jimmie Durham, David Hammons and (as seen at the Walker) Huang Yong Ping are some of the most recognized. How each artist broaches the topic runs the gamut from political to critical, humorous to reverent.

With the exception of “Eternal Trail”, Bois Brulé bypasses all of that and simply illuminates. The artists show the viewer that native culture is more complex than one might think. With a succinct paragraph or two, the wall placards explain the events and people represented, providing a new understanding of women’s roles, religion, the rice harvest and trade in native history. In a nation where cultures regularly mix or collide, there is always more to learn.