Metropolitan Dracula

Lightsey Darst gives us a Halloween feature: she discusses the Metropolitan Ballet's shaggy production of "Dracula" at the State Theater, and talks about a two-hundred-pound gorilla too. We all await their "Romeo and Juliet" later this year . . .

Criticizing the Metropolitan Ballet’s Dracula would be like poking holes in a sieve. Two and half hours long, with twelve scenes, at least five choreographers, and four guest ensembles, the ballet’s both an aesthetic and a storytelling farrago. That the constant shifting of scene, music, mood, and style confuses and tires the viewer is less surprising than that anyone behind the scenes thought this was going to work. An inside critical eye was also lacking in the selection of performers; while some are undoubtedly professional, others have a ways to go. Finally, the performance is plagued with (I hate to say it) technical difficulties—not only long, strange, dark pauses while performers bump loudly into pieces of scenery and burbles of recorded music come and go, but also ill-fitting, unflattering costumes, lights that fail to illuminate crucial lifts, and sound of uneven quality.

But, as I’ve said, criticism is not necessary here. The audience members giggling at Dracula’s arduous romancing of his various snacks and coughing during the extended pauses can all write their own little critiques. It’s far more interesting to talk about what works, and what could have worked.

The ballet opens, surprisingly, with the male half of the Izvorasul Romanian Dance Ensemble stamping rhythmically in traditional dances; later their female counterparts join them. Country dances figure in most story ballets and these, being genuine, add a welcome note of reality to the performance. Alone among the guest ensembles, Izvorasul assists the drama and the narrative. Senseless narrative is to be expected in story ballets, but this one need not be quite so scatter-brained, especially when its heart is Jennifer Hart’s sincerely dramatic choreography. Hart’s responsible for the ballet’s key scenes: Dracula’s duet with his first love, Sylveta; a sketch of Jonathan and Mina’s carefree but rather shallow pre-Dracula life; Dracula’s duet with Mina; and finally, the death of Dracula. Through her distinctively three-dimensional classical ballet choreography, Hart creates a simple tale of dangerous tendencies—Dracula’s obsessive and controlling love matched with Mina’s craving for romance. From this center a moving ballet might grow. Alas, Hart’s story line and characterizations become dissipated among other dance styles and subsidiary stories.

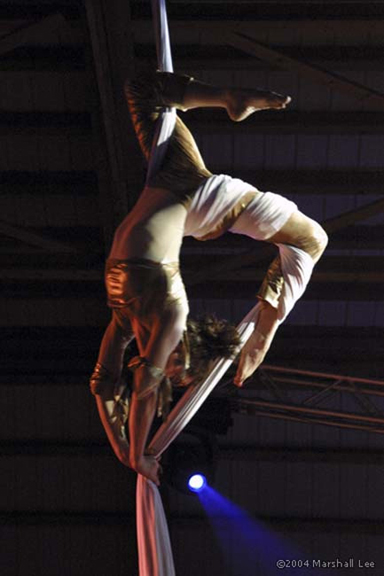

The other choreography ranges from respectable to silly, but the only passage that assists Hart’s central story comes from Risa Cohen and Mathew Janckewski, who combine to render Jonathan’s experience in Castle Dracula. Cohen, an aerialist, cavorts over Jonathan’s bed on blood-red silks, then lures him up into her twisted pleasures. When Dracula comes in for the bite, Janczewski gives him a genuinely frightening duet with Jonathan. Cohen and Janczewski add the edge of erotic violence that a Dracula needs.

The performers have an exceptionally difficult job as they attempt to create characters across choreographic and narrative chasms. Guest artist Norbert Nirewicz (Dracula) is a skilled technician with impressive stamina who sometimes seems exasperated with the choreography. Mifa Ko (Sylveta/Mina) is a beautiful sprite; she doesn’t have the chance to prove she can be a tragic heroine. As Radu/Renfield, Eddie Oroyan’s smooth and preternaturally strong, but his character seems unconnected to the central story. Richard Isaac (Jonathan) fares best: he brings out his character’s comic banality while dancing beautifully.

I see that, in spite of my intentions, I’ve been critical. ThNutcracker or a dance school recital. But the Metropolitan Ballet, which has previously performed three galas but begins its first full season with Dracula, bills itself as “the flagship dance company for the greater Twin Cities”. This claim will set any regular dance viewer’s teeth on edge. The greater Twin Cities can do a lot better than this.

Perhaps the point for the Metropolitan Ballet is that the local dance scene isn’t currently trying to do better. Nutcrackers aside, no one in town attempts full-length classical ballets. The Metropolitan Ballet is founded on the idea that this is a gap in our dance culture. Maybe so. But Metropolitan hasn’t proved that it can perform full-length classical ballets, so we can’t yet gasp with relief at all we’ve been missing over the years. The rest of this year’s season does look much more promising, with Romeo and Juliet in February and a new Midsummer Night’s Dream from Jennifer Hart in June.

Still, if it turns out that Metropolitan can excel at full-length classical ballets, which are undoubtedly a pleasure and an art form whose merits I look forward to discussing, still, “flagship”? It’s certainly unusual that so thriving a dance scene should be without a civic ballet. But it strikes me that the absence of a civic ballet, a dance-scene two-hundred-pound gorilla, may account for the liveliness of Twin Cities dance ecology. However unlikely it is that the upstart Metropolitan will crush out more venerable ballet companies like James Sewell Ballet or Minnesota Dance Theater, the dance community rightfully prickles with fear of such large institutions. Another artistic endeavor adding to the Twin Cities’ fertile mix? Yes, please; Black Label Movement was welcomed as such this past summer. But a flagship? No thanks.