Metamorphosis: North of the Cities

Connie Wanek read the new book of prose poems by Louis Jenkins and thought that they were original and distinctive, as usual, but funnier than his previous work. That must be a good thing.

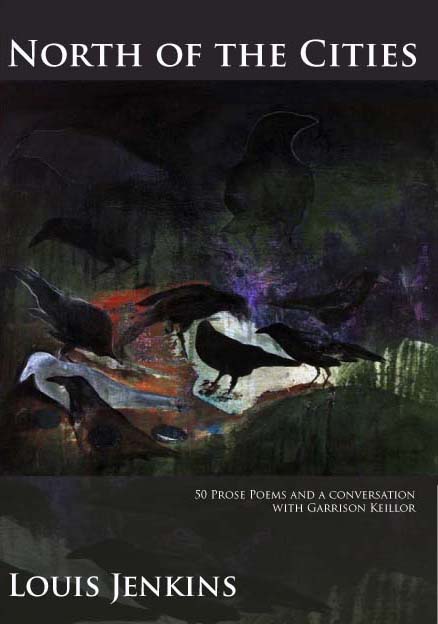

North of the Cities, Louis Jenkins

Will o’ the Wisp Books

The poems of Louis Jenkins have gotten funnier over the years. It’s a natural progression, perhaps—one ages, one makes jokes about it. “We die of silliness finally,” Jenkins says in the poem, “Law of the Jungle,” from his terrific new book, North of the Cities (Will o’ the Wisp Books).

Aside from humor, what makes Jenkins’ work so distinctive and original? He writes prose poems almost exclusively, unintimidating blocky paragraphs, and his language is plain and colloquial. The poems don’t look extraordinary, but within them a turning, a leaping, an almost magical unfolding, a metamorphosis takes place. In an early, seminal poem called “The Plagiarist” a guilty student and the teaching assistant who caught him are seamlessly transformed into a couple dancing at a royal ball.

In North of the Cities the poems are engaged in a more personal, less romantic sort of metamorphosis: the narrator of the poem has decided to be “someone else for a change,” no longer “Lou” but “Art,” an “easy going guy” who “likes baseball.” Art, the man and the enterprise, offers us a new view of the world through the fertility of the imagination.

The poem “Chameleon” describes a woman who changes “her style, her look, her demeanor” to suit the situation and the needs of her boyfriend. The poem “Uncle Axel” is about a photograph, “circa 1890,” with the wrong name written on the back, so that the subject’s identity is afterwards mistaken for generations. Will it ever be corrected? And what difference would that make? Our understanding is provisional; even our identities are not fixed.

Jenkins also undercuts the self-congratulatory and facile. Early and often the reader will find that he deflates the preciousness, the affectation and posturing often associated with poets and poetry, and much humor flows from this flattening of the frothy ego. “My Poem” is written in the voice of an expert on the “Antiques Roadshow” who is describing a poem that someone wants appraised. It begins:

“I am so pleased that you brought this in. What you have is a masterpiece of its kind: genuine, handcrafted, poetry—I’d say late twentieth century, truly a remarkable work.”

The dollar value of the poem is, of course, wildly extravagant. The poem “Baloney” describes a childhood sandwich (“one slice of white bread…and one slice of baloney”) folded over, a bite taken out of the middle. “When you unfolded the sandwich you had a hole…a window, a porthole from which you could get a new view of the world.” Through this hole the poet peers; both he and the world he sees are framed by baloney.

“Mushroom Hunting” could easily describe Jenkins’ philosophy of composition. Like Dante, he begins, “Here I am, as usual, wandering vaguely through a dark wood.” He describes his hunting technique, but then admits, “Every time I find one it’s a surprise. The truth is there is no thought that goes into this. These things just pop up.” The poem concludes with a concise description of the whole of life: “Some inert matter somehow gets itself together, pokes itself up from the ground, gets some ideas and goes walking around, wanting and worrying, gets angry, takes a kick at the dog and falls apart.”

What, then, redeems the sad, silly lives we find we’re living? Jenkins would answer, as Wallace Stevens did, the power of the imagination, which is the source of poetry and the foundation of empathy. Still, let’s not get too serious. In “Ambition” the speaker of the poem has the aspiration to be a cloud. “I’m taking some lessons and have a really good instructor.” To be a cloud is a lyrical notion, undercut by subsequent description:

“I’d like to be one of those big fat cumulus clouds that pass silently overhead on a beautiful day. A day so fine, in fact, that you might not even notice me, as I sailed over your town on my way somewhere else…”

This poem recalls Whitman’s vision of the body after death transformed into grass. “Look for me under your boot soles,” he says in “Song of Myself.”

The poem “Fish/Fisherman” escapes explication. In it Jenkins pays homage, as he has done from the beginning, to the wild and mysterious world beyond our daily getting and spending. In an early poem called “Violence on Television” the reader is urged to leave the car and road on a snowy night and follow a strange figure into the woods, into the world of the unknowable. In “Fish/Fisherman”–but here is a portion of the poem itself:

“After I’ve cleaned the fish and sold most of the day’s catch, I bring a few home for supper. I always put one fish out on the stump beside the shed. In the morning the fish is gone. I don’t know what takes it, if it’s a weasel or a raccoon or a bear or a crow. I don’t watch, or try to track whatever it is. I put the fish out in the evening, and in the morning it’s gone.”

North of the Cities concludes with a short conversation between Jenkins and the humorist and novelist Garrison Keillor. It’s funny and suggestive. Keillor wants more details—what’s in the big brown pills, and who is Jane Kieffer? The poet condenses, Jenkins says, while the novelist expands. Otherwise, Jenkins says, writers are “about the same thing,” which is “trying to make sense of experience.” And having a few laughs along the way.