MCAD/Jerome Artists 2005-06: Dan Tesene

Essays by Kristin Makholm, MCAD Gallery Director and Program Director, MCAD/Jerome Foundation Fellowships for Emerging Artists

Dan Tesene

When Dan Tesene starts to talk about the rapid prototyper that has been a key inspiration for his art during the past couple years, his eyes take on a strange, excited glow. The device—most commonly employed for three-dimensional imaging by architects, furniture designers and the like—has not been used extensively by artists, but has the potential to merge art and science in a way that hasn’t been seen since the development of the camera and the computer chip.

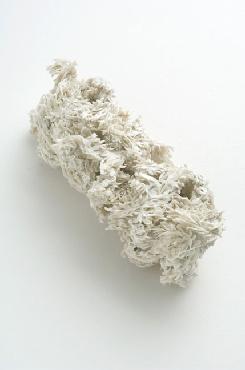

Tesene discusses his brittle gypsum objects and surreal, urban landscapes in terms of old-fashioned printing. Like a print taken from a woodblock or lithographic stone, the rapid prototyper uses a matrix to create a reproduction composed of multiple layers. In this case, Tesene’s matrix is an image drawn in form•Z, one of several available digital animation or modeling programs. In form•Z, a line drawing or two-dimensional shape can be connected or lofted to other lines or shapes to simulate a 3D model. This model can be similarly deformed, rotated and multiplied as the artist desires. The rapid prototyper then deposits layers of gypsum powder and a liquid binding agent onto a plate, building a solid shape that can take from several minutes to several hours to complete, depending on the size and complexity of the object. At the end, the extra powder is blown away and the finished form extracted and soaked in Super Glue for added durability. An object of both fragility and strength, the artist’s invention is made concrete through wizardry that was once only imagined in a Star Trek replicator.

Tesene’s fascination with the rapid prototyper, however, goes well beyond the cool factor. He is interested in how biological growth and notions of space and

time are translated and reborn through technology. It is no coincidence that many of Tesene’s objects look like fossils, vertebrae or something retrieved from the bottom of a coral reef. They are like archetypes of new life, living things transformed into hardened substance from organic matter. Even his cityscapes, constructed again from fine sheets of gypsum powder, seem like biological emanations built up from ages of rock and sand. Yet, like DNA itself, the building blocks manipulated by Tesene are fundamentally structural, extruded through a highly refined coded matrix.

Lately, Tesene has wanted to use technology to capture the image of movement through time, leading him to new work based on the experiments of French 19th-century scientist Étienne-Jules Marey. Like Marey, who in the 1880s led the way toward cinematographic movement through the layering of rapid-series pictures on a single photographic plate, Tesene extracts still images from early animated films and rapid-prototypes them, creating objects that move from still image through movement and back again, retaining the memory of a kinetic experience. In using the rapid prototyper to chart growth and movement, Tesene takes on an almost godlike role as he creates new life from the innermost particles of our digital universe. (K.M.)