Let’s Talk About the “Universal” (White, Male) Artist

In a sprawling essay meandering from Joseph Beuys and George Morrison to recent MFA thesis work by MCAD graduate Nick Rivers, artist Andrea Carlson unpacks the tangled, Eurocentric assumptions inherent in art historical notions of Abstract Expressionism as a bastion for universal, "pure" artistic expression.

I visited Nick Rivers while he was in the throes of pulling together his ideas and materials for his MFA thesis work at Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) in April. He surprised me. I was surprised that Rivers wanted his work, 5 Day Fast: A Performance, to be tethered to his experience and his perspective as a man. He didn’t flinch or scold me for talking about race. Instead, our conversation elucidated for me some problematics that, in turn, have led to this article. After helping myself to a bit of his time and energy, I decided to write the following as a “woe unto young male artists, your road is well-traveled” essay. And this is, in fact, a response to Nick Rivers’s thesis. But before I can get to his work, I have a few items I need to unpack. Allow me to immediately digress.

A temple and a monolith

Modernist abstraction was, and still is, an undying savior which shields a number of artists in any MFA program from expressly addressing race and gender in their work. Their creed: no preconceptions—just raw materials and action and, therefore, art. A man responding only to his initial actions is simple and uncomplicated. Abstract painting represents a freedom from expectations, a freedom from predicting the outcome at the onset, the freedom of pure creation. A conversation about race and gender around Abstract Expressionism (and its offshoots) is an unwelcome guest; it undermines the man of action. This is not, in itself, a bad thing; indeed, it’s an enviable privilege, for there are many who crave just that freedom and find it denied them. Many of us can’t shed the context of our identity so readily; we are actively denied the “universal” lens that makes such content-less expression possible.

The fact is, artists of non-white identities are often perceived as proxies, as inevitably making art from the perspective of their group. The phrase “from the ___________ perspective” surfaces in reviews, and readers are nudged to think that “all of those people share a particular view point.” Turns of phrase, like “from the/a Native American perspective,” may even offer some additional credibility when an artist offers power-destabilizing, anti-colonial views. But shouldn’t decolonization be a critical sensitivity to settler power for everyone? Credibility aside, inserting the phrase “from the white male perspective” in reviews of work by Andy Ducett, Chris Larson, or Alec Soth would likely appear hostile. Regionalism they have, race they do not. Can one really imagine any group of people, let alone an entire race or gender, lacking the complexity and diversity to justify assigning them a single, unnuanced vantage point or perspective?

The heterosexual, white male is also part of a diverse group. The category is not monolithic, but its constituency is supported by a power that, from the outside, appears to be unified, universal, and absolute. This tacit universality means that Eurocentric philosophy is just default philosophy. Writing for the New York Times, Jay L. Garfield and Bryan W. Van Norden call out the assumption, making the case for rebranding of philosophy departments to “Departments of European and American Philosophy.” Expecting resistance, they argue,

Some of our colleagues defend this [default Eurocentric] orientation on the grounds that non-European philosophy belongs only in “area studies” departments, like Asian Studies, African Studies or Latin American Studies. We ask that those who hold this view be consistent, and locate their own departments in “area studies” as well, in this case, Anglo-European Philosophical Studies.

In this same way, many institutions have located “the universal” in Europe and the United States. Museums of ethnographic collections, like the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), also have categorical departments, but they are usually a little broader than the academic “area studies” departments described above. One department at Mia is “Art of Africa and the Americas” (meaning: black artists or indigenous peoples of those continents, typically traditional works); another is “Japanese and Korean” (meaning: traditional works from). In higher education, painting has a department, and contemporary art has a department, but both areas of study skew Anglo-Eurocentric and male. If non-Anglo-European art belongs in departments reserved for traditional works of cultural authenticity and purity, we create a denial of contemporaneity for artists of color. Contemporary African and Native American artists find themselves in a taxonomical no man’s land, integrated in neither ethnographic nor contemporary collections. That said, I understand many museums are listening and slowly making changes, with their own new sets of complications, to mitigate the limitations of such default categories.

Our colleges and civic institutions are presented to us as paragons of culture and learning; they are temples we tend to trust. But such temples are reserved spaces, places set-aside for specific practices conducted as part of a larger, formal context. The Minneapolis College of Art and Design is a temple of sorts, “a place devoted to a special purpose” where congregants learn and teach in the codified context of an “art history”—but it’s an Anglo-European art history and should be noted as such. Those of us outside the dominant category aren’t merely apes throwing tantrums at the base of this monolith. Many of us have, in fact, worked to support the very temples which built it. And there’s a cultural thicket inside those apparently tidy categories: temples within temples, with still more reserved spaces inside them.

One of these nested temples is most certainly Abstract Expressionism.

De Kooning matters

Both I and the late Abstract Expressionist George Morrison—discussed later—are alums of Minneapolis College of Art and Design. When I arranged to meet with Nick Rivers—also, discussed later—I was curious to see what the MFAs are making these days. I was a student there in 2004. At that time, undead abstractionism was less than a quarter of the graduate painter’s output. I attended MCAD a decade after Paul McCarthy made a video work, titled Painter (1995). Painter was integral to my grad school experience; the work presented an alternative, art as cultural critique, and it shamed the sacred out of modernist abstraction. In this video McCarthy cartoonishly impersonates an artist, ramming a phallus-like paintbrush into a canvas while chanting, “de Kooning, de Kooning, de Kooning.” McCarthy was depicting the absurd masculinity of Abstract Expressionism, the artists’ freedom to strap on a paintbrush and make grand statements of genius, to claim a romantic freedom of expression, a freedom to artistic fits of passion. But should one bring up McCarthy’s critique with an abstract painter who was working in the tradition of Abstract Expressionism, the would-be critic was quickly reminded of the existence of Joan Mitchell, with an added caution that forgetting the women who also participated in Abstract Expressionism is, itself, perpetuating sexism. As students, we were told that McCarthy’s Painter illustrated a historic misogyny, but that the art world has come a long way.

McCarthy was right to make Painter in 1995. The modernist framework is, in fact, still with us, and criticism on this history is as relevant now as ever. Today’s MFA student body, comprised of 65-75% female-identified students1, is still living with the celebrated ghosts of those modernists. From an interview in the New York Magazine, titled “Why de Kooning Matters,” Mark Stevens and Jerry Saltz dish the following:

Mark Stevens: Calling de Kooning misogynist is simpleminded. It’s for the finger waggers. It caricatures a complicated sensibility. Sure, anger is there, but so is love, desperation, tenderness, joy, and hilarity. Sometimes crazily all at once. Sometimes in varying proportions. “Beauty makes me feel petulant,” he once said. “I prefer the grotesque. It’s more joyous.”

Jerry Saltz: Well, he also said, “I’m cunt-crazy!” to some cretin who pointed at a red gash in a crotch and asked him, “What’s that?”

M.S.: The hilarity—the scary hilarity—of some of his women paintings is underrated. In the fifties you saw women walking down the street in lipstick and heels wearing—around their necks!—dead foxes with scrunched-up heads and little paws. And by the way, several very important women in de Kooning’s life with whom he had long-term relationships—and most of them were very bright—did not regret the time spent.

Translation: The measure of a man’s misogyny is mitigated by his aesthetics as an artist, and negated even further by the ridiculous attire of the mid-century women around him. It is well-known that intelligent women don’t like misogyny; he had several such women willingly in his life, and, through this association, is given full license to hate women. Or, “some of his best friends were women.”

The promise of universality was supposed to be applied universally. Women weren’t talking about women; artists of color weren’t talking about issues of people of color. They were all just showing up, as modernists, to push around some paint.

I agree that de Kooning’s work is complicated. But it’s still the case that he was free to make grotesque, joyous, and complicated images of women without doing so as a man talking about mens’ issues. He wasn’t ever regarded as making images of women, from the perspective of men; other men wouldn’t allow for it, because men were, and often still are, the curators with the power to dictate representations of themselves in the exhibitions they create. But a woman with a paint brush experienced then, as today, something entirely different if she were to paint similarly grotesque, joyous, and complicated images of men. In an interview with The Art Newspaper, MOCA’s Helen Molesworth explains that,

Most people buy art that in some way reflects their version of the world. Most men—and I hate to take this generalization—but most men think that men make universal statements and women talk about women. You think you’re a universal subject—that is white male privilege. Since the market and the museums are largely still operating under the idea that art needs to communicate universally, this takes a super-powerful toll. When Mary Heilmann makes an abstraction invested in the sphere of the domestic, that’s not a woman thing; that’s everybody. Everybody goes home and stares at a towel. We have a lot of work still to do to show that work by men is just as specific to their concerns and may not be universal. And, contra, that work by Lorna Simpson, for example, is just as universal as work by a white man.

Molesworth’s response here is part of a conversation about gender inequality in exhibitions, but it’s significant that she brings up race. Artists of color also are denied making grand universal statements with their work. Modernist abstraction was supposed to sever rigid context and offer artists the freedom of showing up to a canvas without preconceptions. It was all supposed to be action Jackson. The promise of universality was supposed to be applied universally. Women weren’t talking about women; artists of color weren’t talking about issues of people of color. They were all just showing up, as modernists, to push around some paint.

An artist who happens to be….

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. writes, “To pass is to sin against authenticity, and ‘authenticity’ is among the founding lies of the modern age.”2 Authenticity here isn’t to be confused with personal sincerity, because individuality is sacrificed when a codified racial performance is what’s expected. The fact that an artist would “happen to be” non-white means that artists of color whose work appears to be universal are persistently expected to flag themselves as non-white characters in the Anglo-European experience. We require a trigger warning for our very existence. Louis Gates, Jr. continues,

So here is a man who passed for white because he wanted to be a writer and he did not want to be a Negro writer. It is a crass disjunction, but it is not his crassness or his disjunction. His perception was perfectly correct. He would have had to be a Negro writer, which was something he did not want to be. In his terms, he did not want to write about black love, black passion, black suffering, black joy; he wanted to write about love and passion and suffering and joy. We give lip service to the idea of the writer who happens to be black, but had anyone, in the postwar era, ever seen such a thing?3

A visual artist might look to the freedom of abstractionism, for how could one identify race in work that speaks to materials and action? A wall didactic at Kerry James Marshall’s exhibition, Mastry, at the Museum for Contemporary Art in Chicago relates the anguish of artists of color and modernist abstraction. It reads:

The great promise attached to modernist abstraction in the twentieth century often meant something different for an artist of color. As Marshall has observed, many African American artists held “a belief that abstraction would emancipate them and their artworks from racial readings.”4

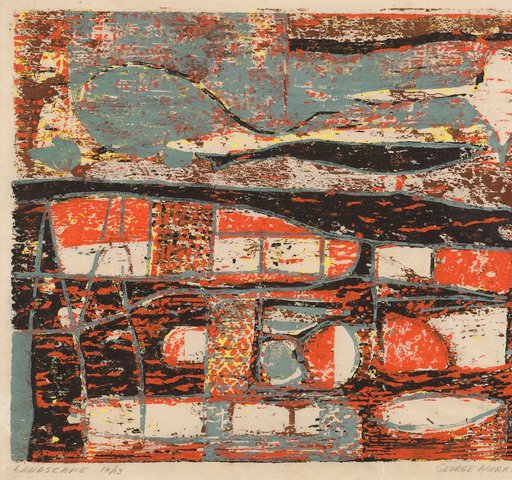

The late Abstract Expressionist and Minnesota native George Morrison also tried to refuse a racial reading of his work. He is often quoted as saying that he was an artist who happened to be Native American.5 W. Richard West Jr. states of Morrison and artist Alan Houser,

Neither wanted to be marginalized as “Indian artists.” Each felt fully equipped to take his rightful place among the leading artists of the day, without any confining labels. I believe they were absolutely right to feel this way. Now for the slightly contradictory part: they are, indeed, Indian artists. You can see it and sense it in the extraordinary pieces they produced. It informs the subject matter, attitude, media and aesthetic vision characteristic of their work.6

But as congratulatory and disarming as that statement is, what if Morrison’s refusal of the “Indian artist” category has nothing to do with merit and everything to do with power? What if Morrison was reaching for universality? Kerry James Marshall states,

For people of color, securing a place in the modern story of art is fraught with confusion and contradictions about what and who they should be—black artists, or artists who happen to be black. A modernist has always looked like a white man, in one way or another. Universality has, unquestionably, been his gift to bestow on others.

I believe Morrison sought that gift of universality. It was a power that he successfully sought out and later relinquished. W. Richard West Jr. speculates that the rejection of Morrison’s works for inclusion in “Indian Art” exhibitions early in his career led to his own rejection of having his art interpreted with expectations of Native Americanness.7 But I suspect his refusal had more to do with Morrison’s own quest for authority over his work; it was his rejection of being an anthropological subject. Morrison’s reclamation of universality for his work meant sitting on the powerful side of the anthropological one-way mirror—the side with both vantage points, the side where the modernists sat. Morrison further declared his modernity with the power of cultural appropriation, delving into various cultures, creating South Asian linga and yoni/linga forms as the basis for his sculptural works. He declared his modernist freedom to a creative cultural harvest, just like Picasso had a moment before. But Morrison was not a wolf in modernist clothing. Despite there being little precedence for people of color having a seat at the table, he had every right to be there.

The freedom to magic oneself with the other

Speaking about the CIA’s modernist art collection, President Truman famously said, “If that is art, then I’m a Hottentot.”8 Truman’s ignorance, and his selection of the Khoisan people to draw contrasts, is in keeping with modernist tastes. The modernists took unabashed joy from dabbling in what they considered exotic, and they were prolific in their gleaning from such sources. Jackson Pollock looked to Navajo sand painting. Gauguin made portraits of Polynesian girls. Picasso had an African period. These artists felt they were elevating non-Western cultures and art forms to the heights of high art. Their benevolence and positioning isn’t subliminal, but rather triumphant and self-congratulatory. Their own ideas must never make contact with those of actual native and indigenous people. If they should happen to encounter Annah the Javanese,9 they could always claim that “some of their best friends were Javanese,” but Annah surely wouldn’t be offered a similar platform to make grand universal statements of her own. Annah with a paintbrush, regardless of what she painted, would be seen as a gimmick.

The idea of the “vanishing colonized” is part and parcel of the end-of-the-trail allegory: the drawn conclusion of Manifest Destiny in its third act, in which the noble savage knows exactly when to gracefully exit off the stage of the American Dream. Only that isn’t our allegorical fantasy, and we, as subjects with our own narratives, need not apologize for showing up to the discourse uninvited.

The modernists didn’t see people of color as their peers and, therefore, didn’t suffer peer review by non-whites. And why should they? It is their fantasy, their own urge to self-transcendence. In The Logic of Modernism, Adrian Piper states,

It is natural that a society dependent on colonized non-Euroethnic cultures for its land, labor, and natural resources should be so for its aesthetic and cultural resources as well. But the impetus in the latter case is not necessarily imperialistic or exploitive. It may instead be a drive to self-transcendence of the limits of the socially prescribed Euroethnic self, by striving to incorporate the idiolects of the enigmatic Other within them. Here the aim of appropriation would not be to exploit deliberately the Other’s aesthetic language, but to confound oneself by incorporating into works of art an aesthetic language one recognizes as largely opaque; as having a significance one recognizes as beyond one’s comprehension. Viewed in this way, exploitation is an unintended side-effect —the consequence of ignorance and insensitivity—of a project whose main intention is to escape those very cognitive limitations.10

But such escape on the back of another’s aesthetic language isn’t free from an inherited grammar, structure, and framework. There are discernible patterns to cultural appropriation. One of these patterns is the desire for, then assimilatiion or eating of the other. Jean Fisher notes that the white male artist who has confounded himself with “tribal” artifacts and sets about producing hybrids “may endlessly incorporate himself as his desired other in a constant disavowel of its absence. As Jimmie Durham dryly remarked, ‘At some point late at night by the campfire, presumably, the Lone Ranger ate Tonto.’”11

But an artist doesn’t need to draw upon visual signifiers or an aesthetic language to make use of Native Americans as allegory. Andrea Stanislav’s 2008 exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts seemed bent on framing Native Americans as an endangered species. I, a Native American, read Stanislav’s brochure at the opening of River to Infinity—The Vanishing Points and learned that Native people “remain more or less as hidden as the few remaining patches of wilderness. We have to make a huge effort to see them [Native Americans], and, even with great effort, what we see is literally vanishing before our eyes.”12 While I made a modest effort to go to Stanislav’s exhibition (the Institute is a couple blocks off of Franklin Avenue, after all— Minneapolis’s “American Indian Corridor”), I’ve never met the artist herself. Perhaps it’s a good thing, as I might have “literally” vanished (a risk I’m not willing to take). The idea of the “vanishing colonized” is part and parcel of the end-of-the-trail allegory: the drawn conclusion of Manifest Destiny in its third act, in which the noble savage knows exactly when to gracefully exit off the stage of the American Dream. Only that isn’t our allegorical fantasy, and we need not apologize for showing up to the discourse uninvited.

American idol no more

The Spirit of Fluxus was a tremendous exhibition, organized by the Walker Art Center in 1993. The Walker has an international reputation for having a significant collection of Fluxus work, and scholars of the work of Joseph Beuys seek out Minneapolis because of this reputation. In 1974, Beuys stopped in Minneapolis, the last city in a three-city tour for his Energy Plan for the Western Man. Beuys must have picked up on the insecurities of the Minneapolis art scene as appearing provincial. Speaking of the trip, Caroline Tisdall writes,

By January 16th we were in Minneapolis, where Beuys spoke at the [Minneapolis] College of Art and Design. The most dominant impression he had of the college was of its amazing rubber floor in the huge video studio, but he was not overwhelmed by such physical equipment: “This kind of art school is for me the least important. A spiritual structure is needed. If a person is an artist he can use the most primative of instruments—a broken knife is enough. Otherwise, it remains a craft school.”13

Beuys was toured around the city: he stopped by Nye’s Polonaise Room for dinner, picked up some sugar packets there, and sold them back to the Walker.14 As hard as I try to make a case for it, Beuys might not be a Minneapolis local-interest subject. Beuys was, however, a German, avant garde-Fluxus-for-a-time artist. Let’s also consider him as an artist who happens to be white, and who dabbled in shamanism.

He was working in a post-World War II era—a time of the Cold War, the energy crisis, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam war. In such dire times, in the thick of so much change, everyone was looking for a savior; I suspect we still are. When one has been brought up by institutions, taught to admire the self-transcendence of the Eurocentric self, we resist decolonizing our minds. We’re trained to empathize on the side of Empire. Despite Beuys’s famous liking of America, and America’s liking of him, I learned to dislike the artist’s romantic transcendence and unquestioned authority. I felt defensive, reading Benjamin H.D. Buchloh article, “Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol.”15 Buchloh criticized Beuys for cloning Nazi rhetoric, his simple idealism and cult-like spirituality. Much of the criticism was directed at Beuys’s own statements about his work and lectures, rather than from the study of any formal attributes of Beuys’s objects. Beuys’s standing in the art world was such that he could make triumphant, grand-gesture statements about Native Americans, such as:

I believe I made contact with the psychological trama point of the United States’ energy constellation: the whole American trauma with the Indian, the Red Man. You could say that a reckoning has to be made with the coyote, and only then can this trauma be lifted.

Despite coming to Minneapolis in January of 1974, Joseph Beuys didn’t meet with Native Americans. (The American Indian Movement (A.I.M.) was founded in Minneapolis in 1968 and quite active by the time of his trip.) When Joseph Beuys returned to the United States in May that same year, he chose to contextualize his performance of I Like America with a narrative of the “Red Man,” while operating on the premise that Native Americans were a conquered people—no longer real Indians, just weakened remnants of their former greatness.

When Native Americans are reduced to romantic allegories of conquest, merely symbolic objects on a chessboard of theoretical negotiations from times past, anything goes. Further, Beuys’s similarly unabashed appropriation from the Celts, Druids, and Tartars went unchallenged. His status among avant garde artists offered both a shroud and a stage, carte blanche permission to make unsubstantiated claims about entire cultures without suffering correction. Beuys could say what he wanted in the temples of contemporary art. Beuys had a stage in these (Anglo-European) spaces and amongst others in the avant garde. And since Natives don’t expect to see their interests served in those spaces (at least, they didn’t back then), we weren’t there to defend ourselves. He wasn’t making his claims about Native American cultures while looking over an audience of brown faces. In such contexts, one is free to speak for and about Native Americans as a means for self-transcendence, but forgoing self-awareness. (It should be noted that Beuys didn’t even let his feet touch the ground for his I Like America trip.)

Then, in 2001, James Luna performed Petroglyphs in Motion, a one-man, runway fashion show at SITE Santa Fe. In one of his arrangements, he donned a Navajo trade blanket in a cone-like fashion, mirroring Beuys’s felt blanket in I Like America and America Likes Me (1974). From atop the blanket’s opening, Luna held a cane— and in later adaptions, a golf club—referencing the Beuys’s cane. Luna imagined his audience as analogous to Beuys’s captive coyote. Luna’s re-enactment serves as a form of peer review; it calls attention to “the fact that Beuys frequently likened himself to a shaman, freely appropriating and romanticizing the traditional practices of indigenous cultures”16 But Luna’s rebuttal, decades after the debut of Beuys’s work, comes too late to force accountability on the artist with regard to native people. Rather, Beuys can be seen as a case study of an artist “magic”-ing himself with the other. When an artist does so subtly and with great applause, the appropriated magic can linger for generations. And in that sense, Luna’s response came, for me, right on time.

In a way, with contemporary critiques of the modernists, we are uprooting an entire attitude and all of the attendant sexist and racist liberties that artists of the mid-century took comfort in. I wouldn’t suggest that white artists stop taking interest in the creative productivity of non-whites, but they should consider the ways in which their affinity for the “other” might be displacing, speaking for, or otherwise exploiting those others in a one-sided power grab. Hal Foster states, “However seduced I am by ideas of historical ruptures and epistemological breaks, cultural forms and economic modes do not simply die, and the apolocalypticism of the present is finally complicit with a repressive status quo.” There is a history and pattern to the decisions we make when we make art.

Nick Rivers: 5 Day Fast

In April, Nick Rivers invited me to the Minneapolis College of Art and Design to discuss his then-upcoming MFA thesis work. Rivers’s plan was to type the bulk of his thesis on a typewriter, while displaying himself in a box made of wood and cracked safety glass, situated on an elevated platform. Over the course of five days, Rivers allowed himself water but went without food and personal space. Like the modern abstract painters, Rivers is drawn to the process without expectations. He cites the methods one might use to find insight, rather than focusing on the finished product, object, or result. The practices of magician David Blaine, philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, artists Joseph Beuys and Mathew Barney all surface in Rivers’s research. Likewise, he draws from the work and ideas of a smattering of male modernist artists, Native American spirituality, and Leonard Cohen to build out a structure of intersecting ideas.

Can we really fully discuss masculinity in purely masculine terms, without also including language and vantage points not steeped in that context?

As he plotted through his sources and some of the connections he was making between them, I realized that he wasn’t just elucidating his craft, but attempting to unpack the universality of white masculinity using the tools of modernism. Rivers is quick to cite the problematics inherent in his research, but he isn’t looking for a different paradigm. Challenging the status quo with the work of feminists, Womanists or post-colonial theorists, at first, didn’t interest him, he said; he was looking for more “purity” in his sources. But this is itself a problem. As Audre Lorde said best, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”17

Can we really fully discuss masculinity in purely masculine terms, without also including language and vantage points not steeped in that context? Rivers, in this way, celebrates the performance of masculinity, its triumphalism, by considering the work of women out-of-scope for his research. It is clear that Rivers aspires to own his context, to give up his claim to universality, but he’s doing so “with the master’s tools” and in ways that won’t hurt his credibility and standing. It is also quite possible that Rivers wants to illuminate a personal context, a singular history around his work, that gives him and him alone authority over the narrative of his experience.

As far as fasting goes, Rivers perhaps saw himself as on a vision quest, but he obfuscated the connection to Native American traditions by citing, instead, the practices of white men and religion as his inspiration. He notes, by way of example, Ludwig Wittgenstein writing his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus while fasting in seclusion; he mentions that all dominant religions hold to fasting at various holidays or to seek spiritual guidance; he cites extreme-ophile magician David Blaine, who went 44 days without food as part of a performance, as well as several contemporary artists who’ve fasted as part of their practice, and, of course, cult leaders who have withheld food as a method for ensuring compliance among their followers.

Rivers reached out to me, I suspect, because I am Native American; he has a close connection to a Dakota community, Native fasting (anthropologically refered to as the “vision quest”), and spirituality. I asked River if he read Black Elk Speaks, assuming that his entry point into Native traditions was as a consumer, but I was pleased to learn that he had a more intimate connection to the community. His references to Native traditions are so slight that most non-native people might not recognize the sources he is drawing upon. In fact, his invitation for me to come see and discuss the work might well be evidence of his abundance of caution and sensitivity about such sourcing.

But I respect the effort to talk to indigenous people directly when work stakes a claim to our traditions and ideas. This is interesting to me. And Rivers is taking steps to not speak on behalf of others, recognizing that he lives in a community where what he says can be heard by those vested in the group. Part of the privilege in being the “universal subject” is one’s ability to jump from culture to culture, speaking with authority over each group, a la Joseph Campbell, without having one’s own ethnic group defining the perspective one offers. Rivers is jumping from group to group, but he is aware of problems inherent in so doing.

The parameters of “good” cultural appropriation may not ever exist. Making oneself humble and vulnerable before the community one is appreciating, or respectfully drawing from, is a good thing. But don’t expect applause for the gesture. It doesn’t seem like Rivers was hoping to magic himself with the other here, because his efforts at “self-transcendence” don’t serve to displace anyone else’s experience. Over the course of his thesis work, Rivers acknowledges that he lives in a rich and complex community, where the ideas of women and natives matter. He doesn’t simply presume these groups are available for his symbolic use.

Before the fast, when we talk in a preliminary studio visit, Rivers’s expectations are full of fear and desire. The document that emerged from his five-day fast likewise starts off restless and romantic, and he writes about his anticipation for stepping into the “unknown.” Early on, Rivers’s “unknown” is filled with sublime imagery, God and light, dichotomies and the problems therein. But the document shifts as the artist’s boredom sets in. His feelings, as a displayed object being photographed by tourists, begin to mark a new level of discomfort with his situation, and that seeps into his writings. Rivers ultimately breaks his “no women” rule in his research and turns to writings by Rosalind Krauss and Julia Kristeva for context, to try and make sense of his burgeoning and disquieting experience of becoming an object on view.

Rivers’s previous work involved building elaborate sets of precariously positioned building materials, ladders, and tempered glass. Some of these materials are held together by, and straining under the pressure of, ratcheted tie-downs. These are objects designed to break; they are held in a state of tension between being broken and whole. Often these elaborate, haphazard systems of things, these industrial objects are nudged by the artist until they break in spectacular displays. Rivers doesn’t consider his involvement to be performance, but he can be seen entering the documentation of the resulting videos. His work speaks to irreparability, endurance, and the breaking points of objects. Placing himself on display is a newer direction for the artist, and it appears he is seeking in this latest work a personal breaking point. One of his first breaking points might well have been seeking out feminist theory when he’d initially decided against it.

The artist’s culminating 16-page thesis organizes tidy lists of references, feverish journal-style writing in which the artist longs for companionship and tires of being on display. The last page, at the end of Rivers’s ordeal, articulates the very boundary of the display box that turned him into a curiosity. It’s telling that, even from his vantage point as an object on view, he still felt more connected to those who gazed in. He states:

Proximity.

The glass is a veil. For some it produces inquisitiveness. For others a feeling of intimidation. The muffling of sound brings people close and their reaching to hear keeps them closer… longer. The barrier suprises people, and some feel bold, in various ways. Some feel accepted to share deep thoughts, some share secrets, like a confessional, some allow the protective barrier to be blunt and abrasive and uncaring. People are multifaceted. There is no single way. What has been interesting to me is that behind this veil, this barrier, the protective film has actually brought me closer to others. What a paradox. That behind an obscured lens, I, along with others feel safe to draw closer.

*********

This is done.

Nick Rivers