Let’s Hear It for the “Farm Team”

Camille LeFevre weighs in on the recent ballet performance by American Ballet Theatre's "farm team" - ABT II - at Northrop, and on the split reactions to the dance program evident in the post-show audience response.

WILL SHE OR WON’T SHE? Will she or won’t she be able to lift her arms into fifth position during the final, devilishly difficult section of the “Rose Adagio” from the 1890 romantic ballet, The Sleeping Beauty? That question remained poised, like a ballerina firmly elevated en pointe, in the minds of more than one balletomane during a Saturday night performance of the career-making (or -breaking) solo a couple of weeks ago at Northrop Auditorium. The real kicker? Skylar Brandt, a 17-year-old member of American Ballet Theatre‘s “farm team”– as artistic director Wes Chapman called ABT II during a performance preview — was dancing the solo, which Chapman also referred to “as a rite of passage for a ballerina.”

And the answer? Yes, she did — and watching her do so was thrilling. The solo in question, originally choreographed by Marius Petipa, builds in difficulty from an opening phrase in which the ballerina is elevated, en pointe, in arabesque while changing hands with four “suitors,” to that concluding moment in which she returns to that pose with the added difficulty of being turned 360 degrees by each guy (remaining en pointe and in arabesque the entire time). After each change of hands, she’s supposed to lift that free arm up alongside her head — where her other arm is already. (That’s fifth position.)

Not all ballerinas do this. But Brandt proved her mettle (despite a bit of wobble, and grimaces before each hand off), even adding the tiny hand flicks — a showy little flourish — while broadly beaming a dimpled smile. While definitely a highlight of the evening, Brandt’s “Rose Adagio” wasn’t the only one. ABT II’s eclectic program of six works ranged from chestnuts of the classical-ballet canon to a charming, French-inflected ensemble piece by rising star Aszure Barton.

Throughout the evening, the troupe performed with a youthful panache and exuberant physicality that largely outshone technical glitches and timing hitches — except during the “Pas de Deux” from Vasily Vainonen’s 1932 Flames of Paris. Marcella Paiva and Colby Parsons danced the showpiece packed with leaps (his) and point work (hers) with sturdy, workman-like technique, and while they displayed more confidence as the duet developed neither exuded a lot of personality.

________________________________________________________

Regardless of the quibbles reflected in some of the post-show chatter, ABT II’s performance made for one of the finest, most pleasurable and diverse ballet programs seen in the Twin Cities for a long time

________________________________________________________

WHICH BEGS THE QUESTION: Should audiences and critics hold these dancers to a different (i.e., less-exacting) standard, because they’re the “farm team?” Answer: Why? Especially when the dancers billed as the B-team are as accomplished as this group of 12. There’s been post-performance chatter about the troupe’s evident faults: their lack of cohesion during unison passages, some rather stiff delivery when a dancer wasn’t front and center, a few dancers’ exhaustion by the program’s end. Some audience members have also wondered why Northrop presented ABT II and not American Ballet Theatre, or even New York City Ballet, which used to make regular appearances: Speculation ranges from economics (lack of funds to bring the big companies) to the perception that Twin Cities audiences aren’t sophisticated enough for the major companies (hogwash).

Regardless, the broad range of choreographic styles presented by ABT II’s program, not to mention the dancers’ level of execution overall, made for one of the finest, most pleasurable and diverse ballet programs seen in the Twin Cities for a long time.

Barton’s Barbara, set to songs by the French cabaret singer Barbara (aka, Monique Andrée Serf), appeared tailor-made for the group. After some initial unsteadiness and lack of cohesion, the dancers breezed through this work of flirty innocence, coquettishly tossing off hip switches, shoulder shrugs, fluttery hands and a sly finger point like so many Audrey Hepburns… or Tatous. The ingénues unfurled their coyness through slender arms, while the garçons clowned impishly. Quick as a whistle, the work was over, the ending left alluringly open, as if simply to announce, “Ça va!”

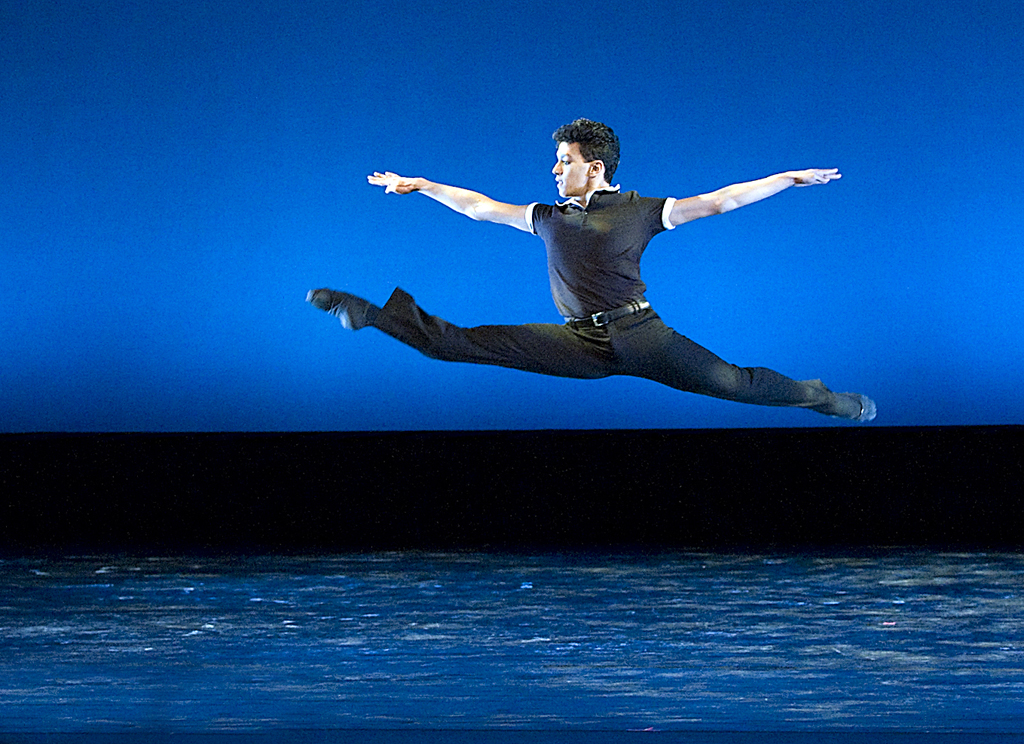

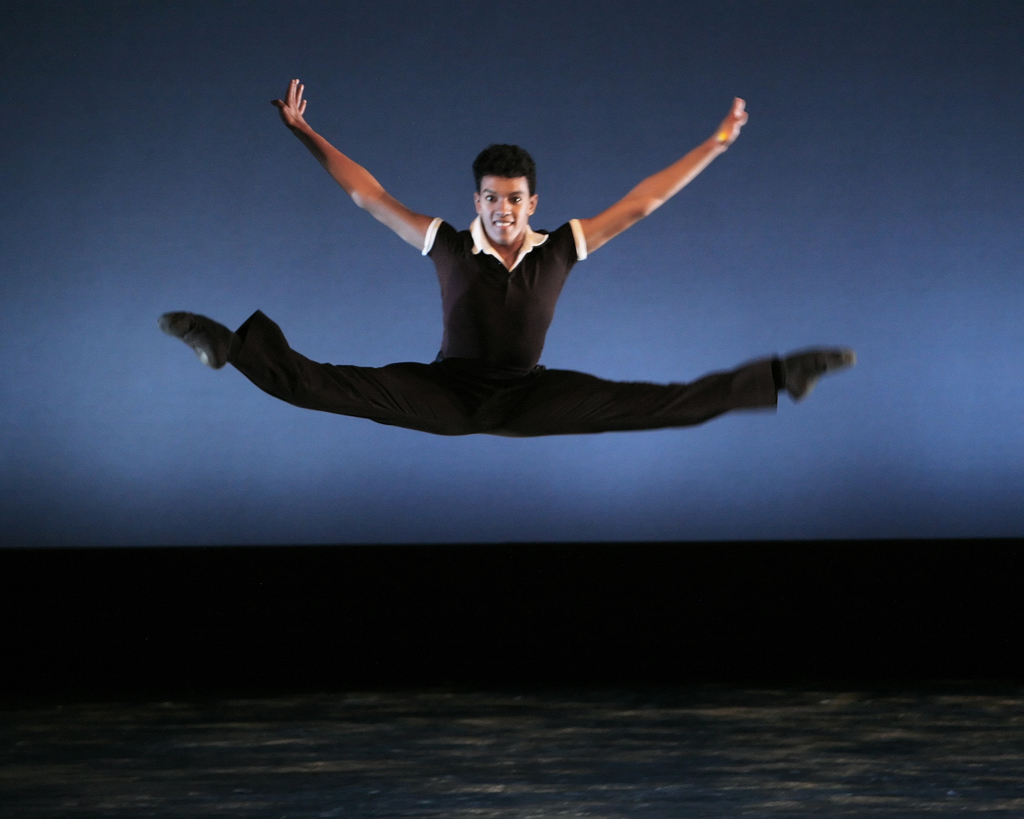

If Barbara was a delightful, well-suited opener for the evening (as well as a teaser for an upcoming performance of Aszure Barton & Artists in April at the College of St. Benedict), Jerome Robbins‘ Interplay closed the show equally well, with a display of jazzy camaraderie. A pre-West Side Story masterwork, Interplay is loaded with leap-frogging and spread eagle jumps, precision spins and rhythmic clapping, playful games of one-upmanship and posing groups in silhouette, all of which the ABT II dancers clinched with flair and vigor.

But the dancers also showed emotional maturity in two challenging works. Kathryn Boren and Calvin Royal III, the leads in George Balanchine’s “everything I know about ballet in 13 minutes” masterpiece Allegro Brillante, were an intriguing match. Royal, who was just accepted into American Ballet Theatre, infused his striding leaps and whipsmart turns with charisma; Boren, in contrast, was an exquisite wisp of gossamer suffused with tensile strength.

The evening’s true surprise, however, was the duet Pavlovsk by Roger Van Fleteren, associate director of the Alabama Ballet. On paper, the work portended a certain degree of pathos, or worse, melodrama in performance: The duet tells the story of an assassinated Russian general and his mourning wife. But Brittany DeGrofft and Alberto Valezquez performed this pas de deux with a refined grace and tenderness that conveyed emotional authenticity.

DeGrofft’s arms gathered, cradled, and flowed through space in lightly veiled expressions of grief. Valezquez embraced DeGrofft through soaring joyous lifts, after which she wrapped herself around his shoulders and chest with feathery elation. They moved like ghosts as they waltzed, a statue come to life and his beloved, their separation momentarily allayed by flowing choreographic expressions of joyous reunion, sealed with a kiss.

________________________________________________________

Watch a short video below of ABT II in performance at the 1.2.3. Festival at the Joyce Theatre in New York City this past spring.

Noted performance details:

American Ballet Theatre’s ABT II performed at Northrop Auditorium at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis on October 9.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is an arts journalist and college professor.