Let the Record Show: Lessons for Artists in Movements

Sarah Schulman’s landmark history of ACT UP is a seed bomb of inspiration and strategy for today

Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 is a seed bomb of history, strategy, and inspiration for activists, artists, queer people, and students of social movements. Twenty years in the making, this political history of AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP New York, contains the intersecting stories of 140 activists involved in AIDS activism. In 2001, Schulman began collecting interviews with experimental filmmaker Jim Hubbard for the ACT UP Oral History Project—this book is the culling and montaging of those 2,000+ hours of archival footage.

Schulman organizes the interviews by theme rather than chronology with chapter headings like: “Change and Power,” “Money, Poverty, and the Material Reality of AIDS Activism,” and “Art Making as Creation and Expression of Community.” The categories offer a scaffolding to understand diverse facets of ACT UP without losing sight of broader conceptual throughlines that Schulman builds about the effectiveness and power of the movement. These throughlines—regarding political power relative to social positioning and employing a diversity of strategies—offer meaningful toeholds for artists within movements to evaluate their own work and goals. Coming from Schulman, a prolific lesbian novelist, playwright, and queer historian, Let the Record Show is an immense gesture of love, care, and responsibility between queer generations. The stories that are shared in this book are either not found anywhere else, and/or these stories are never told with this much depth and integrity.

To me, reading Schulman’s prose was like drinking a cold glass of water: shocking, then centering. It didn’t feel like I was reading a 702-page historical archive. It felt like I was receiving wisdom, grief, and strategy from a very thorough, conscientious elder. Schulman frames AIDS activism as “the last successful social movement in America”1 and presents decades of organizing experience through concrete but conceptually undiluted narratives. Clear about her motivations from the outset, Schulman relays this complex web of narratives in sharp and engrossing language. This book is meant to help future social movements, by detailing the minutiae of strategies, performances, successes, splits, coalitions, deaths, actions, and relationships. The effect is prismatic, not disorienting, and illustrates the amount of respect Schulman has for both ACT UP and her readership.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of things that artists in movements can take from Let the Record Show:

1

A key finding that Schulman outlines through constellating interviews is that “women and/or POC members in ACT UP did not waste their time trying to teach their white male comrades to be less sexist and racist.”2 Instead, Schulman offers that women and/or POC stewarded actual resources like money, energy, and connections towards projects benefiting women, poor people, and people of color. This was a revelation to me, and inspiring after a year of white allies alleging that they were “doing the work” and getting “allyship” fatigued after a few months. As a writer, I especially noticed this phenomenon in the literary world: anti-racist syllabi creation and book purchasing skyrocketed last summer after the Minneapolis Uprising, and Black booksellers across the nation commented on the heinous ways that white customers treated them in that moment of performative wokeness.

In a sense, continually pausing a movement to educate members within dominant groups objectifies the movement; the gesture seats the will and direction of the movement within the dominant group’s purview, and makes revolutionary activity the simple matter of shared language, or understanding. Within ACT UP, there wasn’t time for the stakes of the movement to become diluted by individual acts of language or learning. Because organizers and people living with AIDS were literally fighting the clock, there wasn’t time to waste. People of color and women leveraged power wielded by white cis men who were just now confronting marginalization due to their sexuality and HIV status. “It was the perfect meeting of privilege and principle,” writes Schulman, and, notably, the privilege of the inactive didn’t stymy the activity of those who were on the ground. In 2021, when so much time and energy go into creating punchy infographics or threads on social media, the example of ACT UP begs the question: to what end should marginalized activists educate those with more power and privilege than they have in movement spaces? Is the effort of educating white activists leading towards a material shift in power, resources, or access?

2

The AIDS movement was influenced by all kinds of arts activism: both “big” and “small” art practices, myriad collectives and organizations, and a diversity of values around money, venue, and audience. Schulman notes that ACT UP was possibly the first movement to have so many members with connections to the art world and relationships to cultural institutions. Images created by members of ACT UP were not only influenced by the advertising world, but “benefited from activists who were actually the people who created the aesthetics of advertising.”3 The glossiness, uniformity, and cutting-edge aesthetics would later inform so many movements, and eventually germinate the originary practices of activist video recording.

“Small” art practices included DIY art-making traditions and performance pieces geared towards specific community needs. An example that moved me included the drag performances put on by ACT UP’s Asian Pacific Islander Caucus at a gay Asian-owned club catering to the community. API Caucus members hid information about safe sex practices into red lucky money packets and disseminated information about HIV in this covert and “disarming” performance.4 While bigger works were used to speak out against the government and mass media, these smaller art practices were ways of strengthening inter-community bonds through outreach.

3

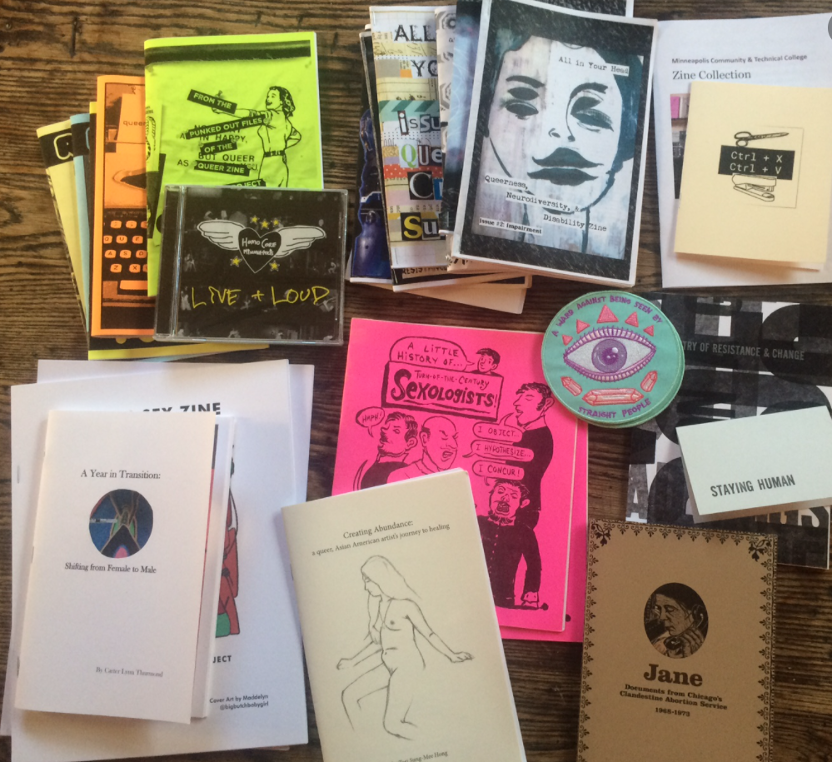

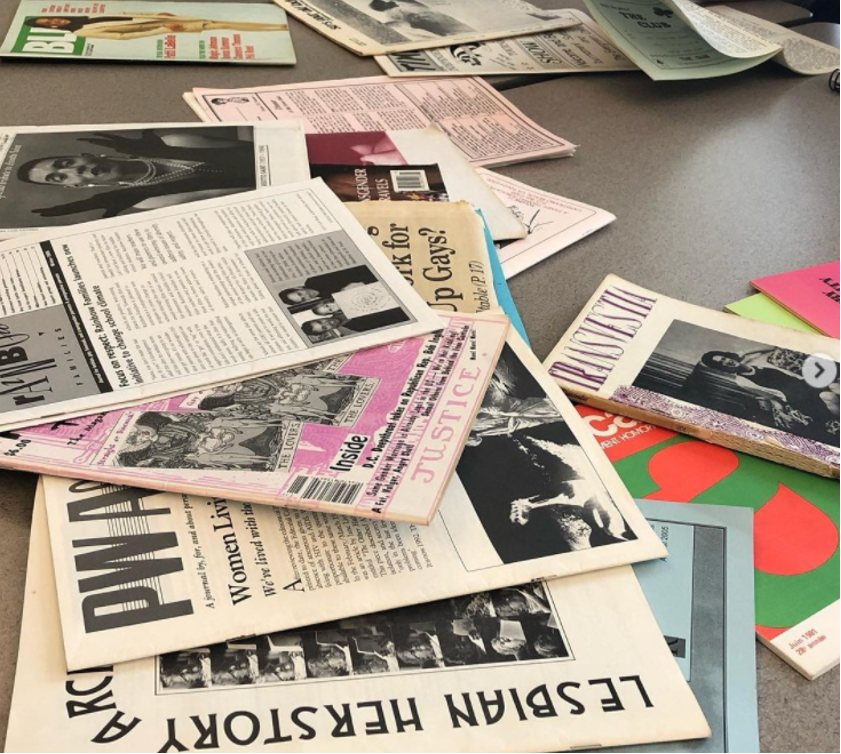

The queer press was an essential tool for unfiltered community dialogue. In the 80s and 90s, queer people were excluded from normative corporate media and queer people of color and lesbians were not given stage time in theaters. Printed material and the presence of queer and feminist bookstores became a network for needed communication.

From 1989 to 1991, OutWeek was a cultural touchstone and leading outlet for queer news, especially news about AIDS activism. OutWeek stood out against other gay and lesbian presses because of its explicitly political nature, ties to ACT UP, and visible phone sex advertisements. Notably, The Advocate did away with their sex ads in order to book a lucrative ad campaign with Absolut Vodka.5 I love this last bit of information because it explicitly illustrates how corporate influence in gay culture leads to the censure and closing down of public outlets for queer sex and explicit content.

In the Twin Cities, the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies at the University of Minnesota offers a series of mapping tools to find LGBTQ periodicals dating back to the 1960s. Titles like Corey’s Story and Save Everything spoke about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Minneapolis in communal, non-institutionalized formats. These archives are a precious lens into the history of queer media in Minneapolis prior to the internet, and include everything from personal ads to comics to safer sex education pamphlets. The existence of these archives emboldens me to be more protective of non-corporatized forms of queer media. One day I, too, would like to contribute to the archives of queer survival beyond what was merely palatable and/or marketable.

4

In the penultimate section of the book, Schulman shares the reflections of César Carrasco, an HIV-positive immigrant from Chile who was involved with the ACT UP Latino Caucus. Carrasco, considering the ongoing trauma of survivors in the present, suggested that activism was a way of making sense of the world: “It creates order, demystifies, and allows an understanding of systems that otherwise feel overwhelming and unaddressable.”6

Reading Carrasco’s outlook made me want to reconnect with the specific and personal role that activism plays in my life. His reflections helped me understand how identifying personal motivations for connecting to activism is different from the kind of egoism that can tear movements apart. Between the COVID-19 pandemic, police brutality and the aftermath of state repression and militarization, the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline, and the ongoing crises of white supremacy, neocolonialism, and capitalism, this last year has been incredibly traumatic. Activism has given my life a container. Without it, I fear that I would be swimming in daily trauma, my life inseparable from it. Activism offers a scaffolding, routine, and ties to a community of real people that keeps me grounded in the everyday.

Coming back to activism as a means of understanding the world and my place in it is, I think, integral to finding meaning within the reality of movement work, which is often slow-moving and disillusioning. I was reminded in this section of a 2015 legal teach-in that I attended after the police officer who killed 22-year-old Rekia Boyd was acquitted. At the talk on a heavily surveilled DePaul University campus, abolitionist Mariame Kaba reminded audience members that it is important to have demands that you can fight for and win, in order to sustain the fuel for larger structural battles. “You lose a lot, you lose a lot, you lose a lot,” Kaba said. “Your job as an organizer is to look for an opening.”

5

In an interview with Tim Murphy for The Body, Schulman said that the hardest part of writing this book was “how to deal with the dead people. There are so many people I never got to interview. How to evoke them.” She evokes the dead in myriad ways through Let the Record Show, most visibly by the short “Remembrance” passages at the end of each chapter, which offer reflections on lost activists by their comrades. Death is ingrained into every page of this book, from the introduction, “Life was surrounded by death,” to the political funerals of David Wojnarowicz, Mark Lowe Fisher, Tim Bailey, and Jon Greenberg described near the end.

It is moving to me that this book is over 700 pages—in that sheer magnitude, I see Schulman’s refusal to individualize this movement. She embraces the disparate narratives, strategies, and actions without losing cogent throughlines: people choose political strategies based on their social position, and perfect consensus does not work in movements. Both of these thematic threads are upheld by the quantity of these narratives, rather than muddied. The effect is dazzling and inspiring, and totally outside of the norm of distilling social movements into a few celebrity figures beyond whom all others fade into the background. Schulman appears to say that the background is the entire picture. Focusing on the action in the background offers a way to walk towards the future as an agent of change, rather than dwelling in the portraiture of individual heroism.

6

The surveillance state impedes the kind of art we can make. Throughout learning about the various art actions, performances, and “zaps,” I’ve been struck by how many more forms of activism were possible before the tentacular reach of the surveillance state impinged on our daily lives. Reading about the July 1991 Statue of Liberty action filled me with a sense of astonishment and envy: members of the direct action art collective Action Tours were able to hang a banner from the crown of the Statue of Liberty without getting arrested. How was this possible? It struck me that it is in some small part becauseof the effectiveness of movements like ACT UP that such intensive standards of surveillance and scrutiny exist in public life today, down to the pervasiveness of nearly all institutions and systematic public spaces requiring an ID. The question of the surveillance state is certainly going to bear on artists in social movements today, and I think the strategies and boldness of ACT UP have a lot to teach us.

7

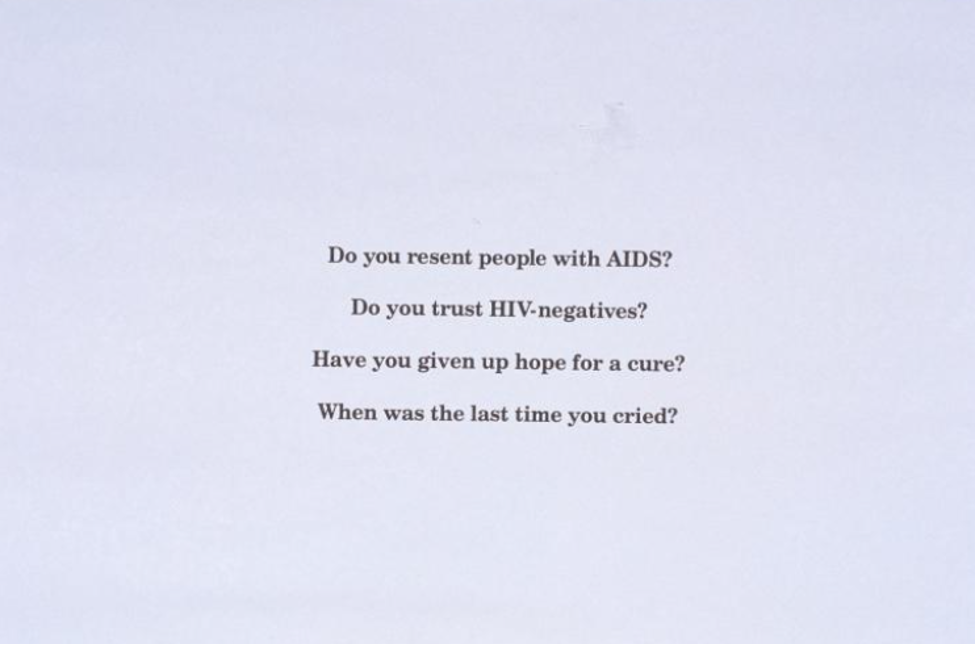

Artists within ACT UP New York not only used art to agitate, but to speak to the immense grief of the moment. Projects like Gran Fury’s The Four Questions and GANG’s Color Bars or All People With AIDS Are Innocent were incredible to learn about because of their sense of scope and emotion. The Four Questions took a year to develop, and emerged out of the sentiment within the artist collective Gran Fury that, with deaths skyrocketing, there were no more statements to make, only questions. The questions were emotional and structured on a huge white piece of paper in a purposefully confrontational manner. They figured the intense alienation, entanglement, and despair within communities affected by the AIDS crisis, both those infected and those who were not. Similarly, GANG’s piece Color Bars or All People With AIDS Are Innocent involved flashing the phrase “All people with AIDS are innocent” against the geometric patterning following programmed daytime television. The short, 10-second piece of art stuck with me as a gesture of honoring the immense grief of people living with AIDS and those who loved them, amidst the mundane cycle of television programming. How small, either in terms of scope or audience, can an art piece be within a social movement and still be effective? How do we judge the effectiveness of art in social movements, especially as these works speak to collective grief?

Queer artist and community organizer Jared Maire shared with me the importance of counteracting grief through moving installations and events. They described the 2007 action Cruising Vigil—organized with the 2000s-era artist and activist collective Revolting Queers—as a moment of joy and collective healing. The bike parade was an “almost joyful funeral procession” that followed the arrest of Idahoan Republican Senator Larry Craig during a sting operation at one of the Minneapolis airport’s gay cruising raids. The procession went through Minneapolis, and ended at Bare Ass Beach in Seward/Prospect Park, where attendants floated lanterns down the Mississippi River and read portions from Craig’s dialogue with the sting officer.

Ritual, and abstract communal processing through art, were also integral to the Grief and Ritual Event that I supported in organizing earlier this year in the wake of the white supremacist shootings in Atlanta. The event was a collaboration between two local grassroots organizations: Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP MPLS) and SEAD (Southeast Asian Diaspora) Project. The practice centered Asian sex workers and led community members through a communal grief ritual, facilitated by the artist and shamanic practitioner Merle Geode. It was a cold night in April, and I processed my grief and rage against white supremacist violence in a way I never had before: wailing against stone, held by my friends and comrades. There is so much possible in collective displays of grief, if for nothing else than to momentarily puncture our ordinary experiences and reveal our shared needs for belonging and catharsis.

And, finally, here is a list of questions that I think artists in movements can consider after engaging with this lively and engaging political history of ACT UP New York:

- How am I leveraging the political options that my social position affords me towards getting resources into the hands of people of color, women, and poor people?

- How am I protecting inter-community platforms for news, media, and communication from corporate co-optation?

- How can I resist individualizing the movement that I am a part of? Is it possible to conduct an oral history or community storytelling event/project for this movement?

- Am I grieving? Is grief a part of my activism? Is grief a part of my art practice?

- How can I resist diluting my message?

- To whom am I dedicating my activism and art? Who can I imagine existing within, and at the ends of the continuum, of my activism and art practice?