Lake Superior: A Character Study

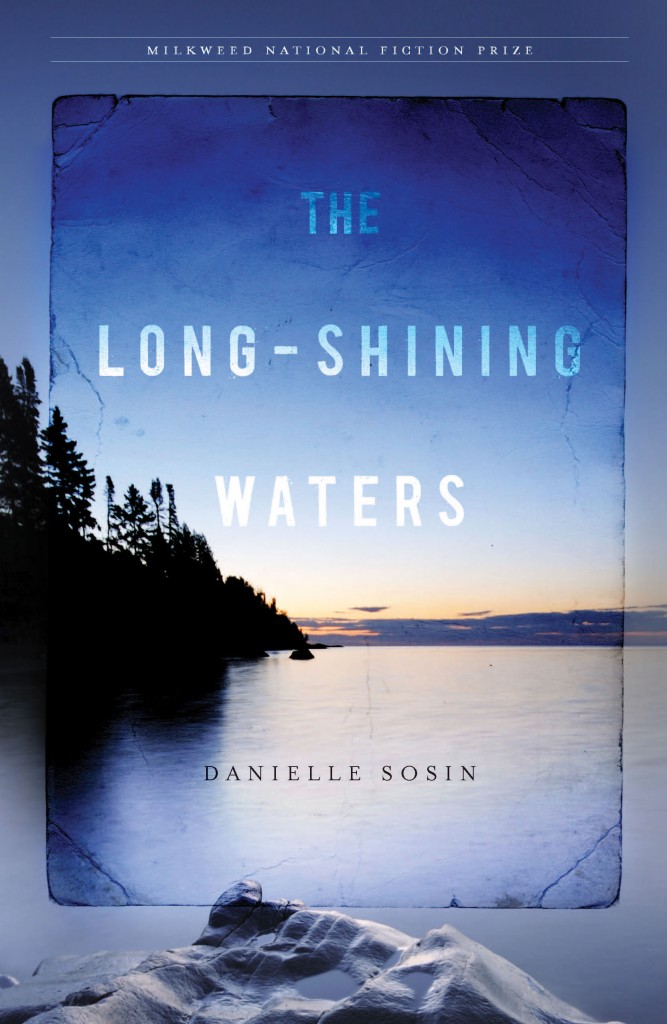

Alison Morse profiles Duluth-based writer Danielle Sosin, author of the new novel LONG-SHINING WATERS, recently published by Milkweed Editions and winner of the press' National Fiction Prize for 2011.

LAKE SUPERIOR, ONE OF THE LARGEST LAKES IN THE WORLD, DOMINATES thousands of miles in not one, but two countries, creates its own climate, and nurtures and kills daily. But today, in the age of lakefront condos, virtual landscapes, and tweets about Republican presidential candidates, the Great Lake’s power is easily overlooked. I confess: I myself tend to the lake for granted.

But Duluth author Danielle Sosin doesn’t. “Weird juju” is what she jokingly calls the lake’s power when I visit her in Duluth one December day to talk about The Long-Shining Waters, her new novel about Lake Superior. Despite the joke, she’s acutely aware of the lake’s magnetic pull and knows just how to invoke it; she has strategically chosen for us to meet at a café with a window-filled back room that overlooks the lake. Out the windows, water and sky merge into a gray field dappled with darkness that signals a coming storm. Inside, Sosin, a striking woman with long black hair, dark eyes, and a voice like a cello, describes some of the ideas and inspirations behind her novel.

I definitely feel the “juju.”

I felt it, too, when I read The Long-Shining Waters, the winner of Milkweed Editions’ 2011 National Fiction Prize. Sosin’s novel braids together the lives of three generations of women who live on the lake: an Ojibwe mother in 1622, the wife of a fisherman at the beginning of the 20th century, and a bar-owner at the turn of the 21st. The book is a pleasure to read, full of gorgeous imagery and unforgettable characters — including Lake Superior.

Sosin was introduced to the northern Minnesota waters by her nature-loving parents. She remembers they took the family to Lutsen when she was five, where she encountered Lake Superior, her first “ocean.” The awe of being a “small body next to a giant” never left. She also recalls fishing with her father on Lake Vermillion: “He would troll,” says Sosin, “moving really slowly, about 20 feet out from the shoreline. I would watch the woods and stones and lichen go by. To me, that place where stone meets water — all the better if it has lichen on it — is just the best landscape.”

Later in life, Sosin and her friend and mentor, writer Pat Francisco, made a summer ritual out of renting a cabin on Superior’s north shore for a week of “hanging out” and writing. Sosin also attended Norcroft, a north shore women writer’s retreat then was awarded two separate month-long stints alone at Norcroft’s alumni cabin. Drawn to its shores again and again, writing there over so many years, she wondered: “What is it about Lake Superior that so moves and haunts me?” She even attempted to write a story about it some years ago, she says, but the idea “was too large to succeed” in its first incarnation. At that time, Sosin had already published a short story collection, Garden Primitives, with Coffee House Press, and wanted to try her hand at something longer and with more depth. Her “failed” short story about Lake Superior became the germ of a novel.

The Long-Shining Waters took eight years to write. First, Sosin immersed herself in Superior-related topics, like the lake’s weather, shipwrecks, geological and industrial histories, as well as stories of the people who live or have lived there, from the Ojibwe — lakeshore residents for hundreds of years — to the area’s more recent immigrants. Eventually, she moved to Duluth to focus more deeply on the novel. She was only going stay for a year — nearly ten years later, she’s still there.

About a year-a-half into Sosin’s project, one of her close friends died. “That loss is all over the book,” she says. At one point in the writing process she admitted to herself: “I’m writing a fucking requiem.” But that fit the way she saw Lake Superior: “It’s so beautiful and so enticing — and it’ll kill you. That’s fascinating, kind of like life.”

______________________________________________________

At one point in the writing process she admitted to herself: “I’m writing a fucking requiem.” But that fit the way she saw Lake Superior: “It’s so beautiful and so enticing — and it’ll kill you. That’s fascinating, kind of like life.”

______________________________________________________

Sosin insists that the lake is a “haunted presence,” where “things of the past are also present,” creating what she calls “simultaneity of time.” In The Long-Shining Waters she builds a world where three linear narratives, from three different time periods spanning 400 years, seem to overlap in time and space. She also creates a fourth narrative voice. “I was working on the book and getting so frustrated trying to move the stories forward,” says Sosin. “I just wanted to play with words. So I would, as a treat to myself, spend a day or two writing reflections about the lake.” She decided to add them to the book. Then, after years of working on them, she realized she had written the voice of a new character.

I move with the rhythm of dragonflies.

They are here. Aloft in the water currents. The small. And their ancestors, whose long pulsing wings ripple the shadowy images. A luffing sail. A crate of lost lemons. A silver button tumbling to the lake bed.

The Long-Shining Waters reads like a novel in verse, even though Sosin claims to be a “poetry idiot.” Instead, she cites Virginia Woolf’s fiction as one of her strongest influences. “When I first read Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and saw that the minutiae and inner lives of characters could make great art — that just blew my mind.” She also loves Annie Dillard‘s writing for its strong images and the rich interior life it depicts, and for its intellectual rigor and surprising juxtapositions. Sosin also acknowledges the strong influence of music on her writing; she played cello for years, and mentions that she finds the two to be very similar art forms, saying that both are experienced over time and involve “balance and tone, getting louder and getting softer.”

She knows her style of writing isn’t for everyone. Early in her career, as a “mentee” in the Loft Mentor Program, one of her two fiction mentors took a red pen to the story she had submitted for review. “‘What’s with all this description? Just get to the story.'” But her other fiction mentor, James Welch, loved her abundance of detail, and she says that gave her the confidence she needed to pursue her singular style.

In fact, Sosin has consistently followed her own path: she studied political science, women’s studies and psychology in college rather than creative writing; she has always worked part-time in fields like gardening and restaurant work to give her the social and physical outlet she craves after mornings spent at home, writing in solitude. “I need that sort of balance,” she says, “and a flexible schedule. But I’d be happy to do short teaching gigs that pay.”

Danielle Sosin’s strict adherence to her own vision pays off in this uniquely satisfying novel. The Long-Shining Waters is as observant and smart as its author. Never sentimental, yet filled with feeling, poetic but alive with complex characters and drama, her book makes the spirit, history, and concrete presence of Lake Superior palpable and relevant.

The Great Lake is movement at peripheral vision. It is sound at the limit of audible frequency. It is the illusion of the ability to understand.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Alison Morse‘s poems and stories have been published in Water~Stone Review, Natural Bridge, The Pedestal, Rhino, Opium Magazine, mnartists.org and other places. In 2011, she wrote a collection of stories about Kenyan social justice activist Wahu Kaara for the Women PeaceMakers Program at the Joan Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice, which will be published in 2012. She also teaches English and runs TalkingImageConnection, a reading series where poets and prose writers respond to visual art in Twin Cities galleries. The next TIC reading, on May 12, will respond to the show, FLO (we) {u}r, at the Soap Factory.