Kinky Friedman

The Ruminator Interview

Richard Friedman was born near Palestine, Texas to an educated middle-class Jewish family. He’ll tell you that’s why he never made it as a country singer—he just didn’t have the same “opportunities” for a fruitful career in country music afforded to those with troubled, impoverished childhoods. In college a roommate dubbed him “Kinky” for his mess of curly hair and the moniker stuck. Inspired by Kennedy, Kinky Friedman joined the Peace Corps in the late-’60s and served in Borneo, where he’s claimed his primary accomplishment was to introduce the Frisbee to the natives, which they used to make their lips big.

When he returned to the States, he had a brief but celebrated career writing and performing irreverent country songs with his band (Kinky Friedman and His Texas Jewboys) like “They Ain’t Making Jews like Jesus Anymore” and “The Ballad of Charles Whitman,” eventually even touring with Bob Dylan. Though the band developed a cult following, The Texas Jewboys’ star faded by the late-’70s, and in the mid-’80s Kinky began a successful second career as a mystery novelist; his well-loved, hilarious mysteries feature a band of misfits called the Village Irregulars led by a hard-boiled, politically incorrect detective (with whom Kinky shares his name and quick tongue) who solves murders and tosses off one-liners with equal ease. He’s one of the few authors who can count both President Bush and President Clinton among his fans. His newest, and final, installment in the series, Ten Little New Yorkers, has just been released. He’s an enterprising philanthropist. Taking cues from Paul Newman, he’s tried his hand at life as a food impresario—offering proceeds from sales of Kinky Friedman Private Stock salsa to the Utopia Animal Rescue Ranch situated on his property and partnering with Farouk Shami to sell Holy Land olive oil, with all the profits going to fund summer camps for Palestinian and Israeli children to get together.

At 60 years old, Friedman has stopped writing novels, and in early February he announced that he was making a bid for the office of Governor of Texas. His politics have grown more complicated—he’s not easily pinned to the Left or the Right, no longer the child who cried over Adlai Stevenson’s loss. Ruminator spent some time recently talking with Friedman about his run for governor, the role of outsider candidates like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jesse Ventura, and about restoring the cowboy to a place of honor in Texas.

Susannah McNeely: I seem to remember a year or so ago in a television interview, you said that at 60 you wanted nothing more or less than to be the Salsa King of Texas. And after your bid for Justice of the Peace in ’86, you said you were leaving “that worthless tar baby that is politics” to the young people. What happened that changed your mind and prompted you to run for governor of Texas?

Kinky Friedman: Nothing changed my mind, that’s still correct. This is not a political campaign. It’s a spiritual one—a spiritual calling.

SM: What do you want to do?

KF: I want to change the face of politics here in Texas, and I don’t want to do it politically. Just like Arnold, I want to get rid of the career politicians. And once we do that, I’m going to get the Californians out of Texas.

SM: [laughs] So you’ve got a big problem with Californians in Texas these days?

KF: It’s part of my “anti-wussification” campaign.

SM: What is it that you think has become wussy about Texas?

KF: I think all of America has become wussified, and Texas is the last stand against wussification.

SM: How so?

KF: Well, you’ve got people falling all over themselves to apologize for saying “Merry Christmas” for instance. That’s a good example. It’s political correctness gone awry. Smoking regulations are strangling the live music scene in Austin, the live music capital of the world. Another example is prayer in schools: people are afraid of even nondenominational prayer in schools, and I say, what’s wrong with a kid believing in something? And now it’s the cowboy, the word’s being used derogatorily; and I think that’s wrong.

SM: How do you think “cowboy” has been used pejoratively?

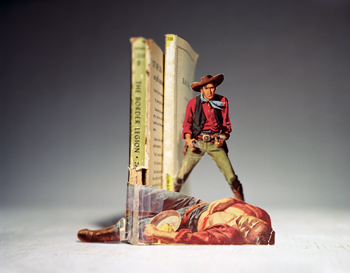

KF: By Europeans, by some Americans . . . maybe it’s because of George W., maybe not. It’s been used that way to mean a loose cannon or a bully. But a cowboy has never been that. A cowboy has always stood up for the little people. He’s always been a knight out of time, beloved by all the children of the world. I want to preserve the cowboy as he really is. I want to take us back to a time when the cowboys all sang and the horses were smart. I’m gonna beat this wussification, if I’ve got to do it one wuss at a time.

SM: As a spiritual leader of Texas, restoring the faith in the way things ought to be?

KF: That’s right, I’m looking to do spiritual lifting instead of heavy lifting. That’s what I’d do as governor.

SM: So does this idea of the honorable cowboy have anything to do with why you threw your support behind President Bush in this last election? You did, didn’t you?

KF: Yes. I did in this last election, but I didn’t vote for him the first time.

SM: Who did you vote for in 2000?

KF: I voted for Gore then. I was conflicted. . .but I was not for Bush that time. Since then, though, we’ve become friends. And that’s what’s changed things.

SM: So it’s your friendship with him that’s changed your mind about having him as president more than his specific political positions?

KF: Well, actually, I agree with most of his political positions overseas, his foreign policy. On domestic issues, I’m more in line with the Democrats. I basically think he played a poor hand well after September 11. What he’s been doing in the Near East and in the Middle East, he’s handling that well, I think.

SM: As an independent candidate running for office, if you get elected how will you get things done? Jesse Ventura won the bid for governor here in Minnesota, but once in office, he had a hell of a time getting much through the legislature. Part of that may have been related to his own confrontational way of dealing with people, but part had to do with a lack of political capital and allies in the legislature. How are you going to overcome those sorts of difficulties to get things done?

KF: Well, you can’t get stuff done by going through the Texas legislature, anyway. We’re only safe when they’re out of session. I’ve said before, about Jesse, that he’s really inspiring because he believed that the guy with the most money shouldn’t always win—that elected office shouldn’t just go to the highest bidder. What Jesse didn’t realize is that wrestling is for real, and it’s politics that are fixed. And if it’s fixed, I want nothing to do with it. Imagine a governor with no strings attached, nobody owns him, totally untainted by politics. Imagine a state where musicians run the government instead of politicians, with a lot of young people involved. That might really work. Arnold’s beginning to do the same thing in California. The real issue is whether we can knock down this windmill of politics as usual. If we can, we’ll make the lone star shine again in Texas.

To finish reading this interview, visit Ruminator’s web site www.ruminator.com