Kinji 101

Designer Kevin Byrne offers an engaging, philosophically-minded primer-cum-tribute to his longtime friend and colleague at Minneapolis College of Art and Design, acclaimed artist and educator Kinji Akagawa.

I ATTENDED COLLEGE ASSEMBLIES AT THE MINNEAPOLIS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN (MCAD) where, for exactly thirty years, I sat next to Kinji Akagawa. In my first year, we were bad boys: We would joke, too much and in a less-than-silent fashion. That was insufficiently “Minnesota nice,” so the next year I moved over a couple seats from Kinji and sat next to an equally warm-hearted — but better behaved — colleague. Actually, I think it was at that meeting she was elected assembly secretary, a position she would retain for several decades. She did a fabulous job in that capacity, but with one hitch: She could not understand some of Kinji’s contributions, particularly on those occasions when he’d offer facts and opinions of a philosophical nature. At those times, to keep her minutes accurate, she would lean over and ask me, “What did Kinji just say?” As I had attended a Jesuit university and gotten a full dose of philosophy and theology, sometimes I could offer a decent “translation;” at other times, honestly, I had no idea either.

Though Kinji and our assembly secretary each retired from MCAD three years ago, I pledged to both of them I’d share something in writing which could serve at once as a tribute to Kinji (as an artist-philosopher-mentor), as well as a tutorial for the rest of us, who, forever his protégés, colleagues, and/or students, might yet benefit from a refresher: Kinji 101, with two lessons…

But first, a brief history:

Imagine an artist as he looks out onto a rain garden that he designed in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The artist is Kinji Akagawa: born in 1940 in Tokyo and educated at the Kuwasawa Design School. Although Akagawa is now widely known and treasured for his philosophical depth, his enrollment at Kuwasawa, a design institute modeled after Germany’s Bauhaus School, also helped shape his art and life. Kinji has said he relished his school’s “interdisciplinary learning and [became aware of] the importance of democratic design, materials and architecture” as a student there. (Akagawa, 2009, unpublished artist’s statement) In 1963 the young Akagawa boarded a cargo ship for the U.S., where he attended Haystack School of Arts that first summer in Maine, and later attended Cranbook Academy of Art in Michigan. While at Cranbook he received a grant to work at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles under master printmakers and world-class artists. He later earned a baccalaureate diploma from MCAD and his MFA from the University of Minnesota. Since 1973 almost all of Akagawa’s practice and teaching has been in the Twin Cities. He retired from teaching at MCAD in 2008 and is slated for the award of MCAD Professor Emeritus this May; he even has his own web tribute on Wikipedia.

Lesson 1

After over a decade of readings and discussions inspired by his MCAD faculty, colleagues, and friends (Siah Armajani, David Nye Brown, and others), Akagawa developed his own, unique approach to making art. Atop his list of philosophical mentors is the great 20th century German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Kinji’s distillation of Heidegger has always been a moving target, but summarized it might look something like this:

- A creator chooses tools and materials in a very considered fashion.

- A creator makes a site, sometimes pondering audiences while the making happens; making includes sawing, hammering, drilling, painting, et al.

- An audience emerges, comes to the site, and dwells within it.

- Dwellers sense (see, touch, smell) — then think about — what they are experiencing, and then they swap stories.

- Part of storytelling involves reliving some or all of the genesis of the making; let’s call that remaking. Any kind of remaking preserves the original site. (Caveat: my one sentence here is hopelessly inadequate.)

- A remade site invites the audience to dwell inside again and again. (Back to stage 3 now, and the cycle continues.)

Got it? If not, reread 1-6 above. Got it yet? If not, read Heidegger, 1982, and Inwood, 2000, both cited at the end of this essay. Got it now? If yes, let’s try an exercise to apply this rubric.

Exercise A: The work of Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer (1900 – 1985) was born in northwestern Austria and had no formal art education. He apprenticed with an architect-craftsman in an atelier in Linz, later moving to Germany where he worked at an architect’s studio near Darmstadt. Bayer attended the Bauhaus School, and later taught there. As World War II approached, he emigrated to New York. Bayer’s productive life as a pioneer of modern design continued in America for nearly a half century. I am choosing an example of Mr. Bayer’s work in Colorado for this exercise because 1) Bayer had direct connections to Akagawa (notably, Bayer was at the very root of Bauhaus learning and practice so important to Kinji; he was also a mentor to him during his year at Tamarind, and, prior to retirement, Akagawa taught for a semester at the Bauhaus University-Weimar); and 2) I have a personal connection to the site that goes back over 35 years. The particular piece we’ll consider here is Anderson Park, Aspen, Colorado. Now let’s apply that “Heideggerian rubric” to the work of Akagawa’s own mentor:

- Bayer’s materials were water, earth, grass, stone, and concrete; a list of his tools would be much longer. (There’s more to say here, of course, but this will suffice for our purposes.)

- Bayer was an acclaimed designer, so both clients and audiences came as a matter of course; the many regular visitors to the Aspen Institute readily served as the latter.

- Audiences came to the site, and some dwelled there. I felt lucky to see Anderson Park the first year it opened, while I was attending the International Design Conference on the Institute grounds in June. Given the zeitgeist (early 1970s) and that we were cheap grad students at the time, a couple of us were literally “dweller-wannabes”: we liked it so much we found a campground in close proximity in order to “dwell (nearby).”

- Sensing and thinking about the site were both quite extraordinary experiences. I have slides somewhere that capture some of the sensing, but you should try it for yourself, if you have the chance to visit. I remember getting box lunches during the conference break, then going over to the park to explore. (Today, Google Earth, Bing, and panoramic software websites make virtual visits to the site possible, even at a distance.)

- Reliving the site’s genesis was tricky that week in 1974; I didn’t do that until a year later. In the interim, I had time to research the site’s development and revisit the park at the next conference; in a way I remade it at the time by mentally draping my research atop Bayer’s landscape. For example, I learned the site had been literally recreated by Bayer himself, in an earlier era; his first piece on those grounds was Grass Mound, completed in 1955, and remade into Anderson Park less than 20 years later. (If I were to tell Kinji about this, I suspect he would immediately compare it to Japan’s renowned Ise shrine, but that’s another story.)

- Via Google Earth (GE) or Bing, I can now “dwell inside there” just about anytime I want. In fact, with the arrival of GE, I virtually revisited the site and noticed something I had forgotten: the conference’s famed “events tent” that Bayer had designed the previous decade was at the opposite end of the Aspen Institute’s grounds from Anderson Park. At the time, the two sites, though distant, felt well connected. I recall puzzling back then as to how this could be; I thought it might have something to do with their geometries: the mounds and swales of the park seemed to echo the roof of the tent. They both feature a complex but lovely mix of concave and convex volumes and shapes, large and small, in perfect visual counterpoint. With the aid of GE, I now noticed both the tent and Anderson Park had footprints of nearly identical size. Whether the reasons for my sense of connectedness between his distant designs are subjective or objective, we can happily go back to Bayer’s own writings for his commentary: “It is difficult to separate [my] sculptures and environmental design because they are so closely related…I see outdoor sculpture always in relation to its immediate environment.” (Cohen, 1983: 407) I wonder: Might Heidegger have approved of GE?

Lesson 2

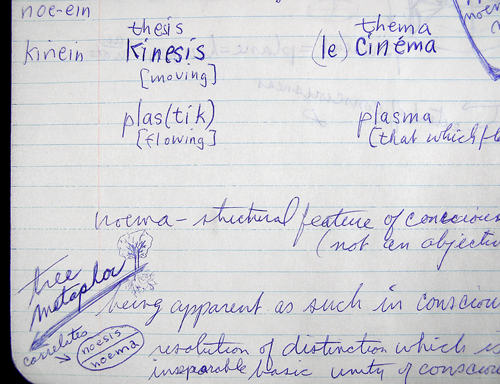

Thinking, referred to in stage 4 of Heidegger’s rubric, is usually done alone, though we could put an interactive spin on it by considering such musings to be “conversations with ourselves.” Kinji prefers that thoughts and experiences of art and design not be solo, specifically that they be intersubjective. And he is quite adamant about that. Forty years ago I took a university class in phenomenology, the study of consciousness; in particular, we read and discussed Edmund Husserl, philosopher and pioneer of the discipline. Husserl was the initial champion of intersubjectivity, later working with a protégé on a companion methodology, known as iterated empathy. Iterated empathy is conducted as follows: Put yourself “into the shoes of another” (and ask that s/he do the same with you). Here’s a summary of the steps:

- Let’s not worry whether, for example, a tree “over yon” actually exists — its existence doesn’t really much matter; rather it is the appearance, and the experience, of the tree that we care about. (If the truth be known, Husserl might be the one who actually first promoted the idea of what, today, we call “experience design”!)

- As practice, come up with a way of describing and explaining that tree as if to an “uninformed alien.” Then do the same for a work of art, say of a tree. What do you see, what does it look like? Write it down or sketch it.

- Iterated empathy next asks us to experience another person (often called the Other) as a subject, rather than as just one of many objects in the world. Once you can “view” from the Other’s eyes, go ahead and look at an artwork. What do you see? So far, so good?

- Now reverse your perspective and experience yourself as seen by the Other. Then, again, have a look at that artwork as seen through your eyes as seen by the Other. (Sorry, this sort of experiential layering is typical of busy little phenomenologists at work.) What do you see? Write it down or sketch it.

- So, just what have you now seen? What have you accomplished? If you are lucky, you’ll know now that the world at large is a shared world, instead of one available just to oneself. (If not, repeat steps 2-4 until you have achieved such a shared perspective.)

- By the way, it does not have to be a perfect sharing, referred to by some phenomenologists as weak intersubjectivity; imperfect sharing is quite OK, and that’s called strong intersubjectivity. It would not hurt to think of moments of sharing as existing on a continuum.

Now, let’s wrap up the Husserl rubric by zooming back and adding another voice, with an explanatory quote: “Art calls for an observer or interpreter…Yet great art…is not consumer led: it changes one’s way of viewing [and navigating] the world. [Art]work is not like a drug, and the experience is not private; the work is communal and grounds our relationship to one another.” (Inwood, M., 2000: 122, italics mine)

I tried out Husserl’s iterated empathy using an exemplary, site-specific piece of outdoor environmental design, and it works! Husserl’s rubric is complex, so the narrative of my results is lengthy enough to preclude featuring it here. Even better, I think, would be to cut to the chase and close Kinji 101 with a homework challenge for you.

Exercise B: Peace Garden Bridge

I propose as a possible homework, that you conduct your own experiment in iterated empathy by examining the Peace Garden Bridge, designed by Akagawa himself, together with Jerry Allan, an architect and professor at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. According to a 2009 “News & Events” article for the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board: “Situated under willow trees, the bridge encourages visitors to pause and reflect on their surroundings. Japanese tradition also says that evil spirits walk only in straight lines, so the zigzag bridge prevents them from following people into their garden retreats.” There are histories underlying the Peace Bridge — cultural, contextual, financial, et al. For example, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board gave authorization for the effort to the Peace Garden Project Committee to raise funds to finance the project; phenomenologists are a picky lot; some might care about the practical history and context of this site, others might not. But all agree you have to see it, experience it; thus you must: 1) Visit the site, which Kinji would prefer, or, at the very least, 2) experience it remotely via photography, the web, etc. Remember, iterated empathy can not be performed alone, so find a partner. Happily, the Twin Cities public television recently broadcast an episode of Minnesota Original featuring Akagawa’s work, specifically Peace Bridge, which you may watch below.

Epilogue

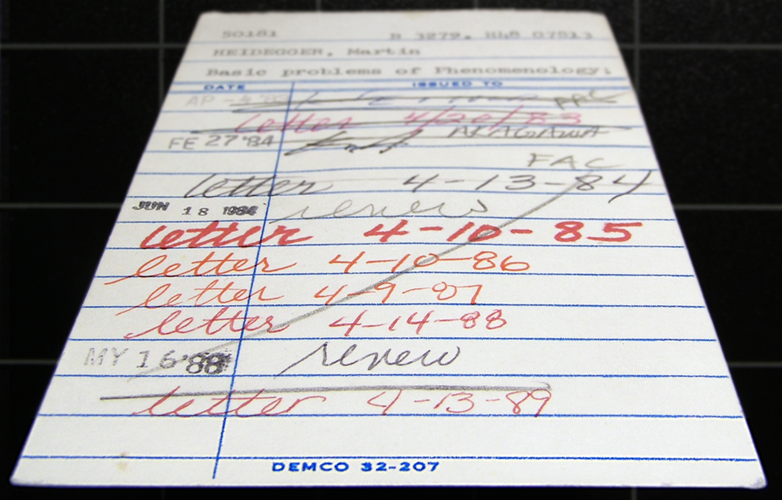

It is entirely possible that I may have gotten some of this wrong; even so, I have a feeling Kinji wouldn’t really mind, because even in error I have undertaken a “journey of epistemology and aesthetics” on my own, after which “going public” with results via this essay; in so doing, I both struggled with and benefitted from the writings of great mentors as guides. While reacquainting myself with Husserl and Heidegger, I spent time pouring over my college notes and poking around the library stacks at MCAD. As I was checking out Heidegger’s Basic Problems of Phenomenology, a card fell out from the back, the kind we used to fill out by hand. I noticed it had a just over a half-dozen sign-outs, dating from its accession in 1984 until the end of that decade, after which the library must have gone digital. Clearly Akagawa loved Basic Problems, as he had it out for six of those years; I just checked it out myself (Lesson 1, in part, was the result). When I inquired about this to Kinji, he joked about his pattern of renewing the book: “Yes, they ended up letting me do it yearly!” I also asked him about a signature atop the library card, an MCAD colleague who was the first to check out the book. Kinji indeed recalled him, and without hesitation, saying, “Actually he was a more of a semiotician than phenomenologist” – but that’s not all. Kinji Akagawa is a walking encyclopedia: He then told me exactly when and where the colleague, a videographer, had studied philosophy during his university years.

I’m beginning to think the world could use yet another course, a Kinji 102. What more could we uncover/discover about this artist by applying some iterated empathy to the Twin Cities’ own “professor emeritus of art and intersubjectivity”?

______________________________________________________

About the author: J. Kevin Byrne tries to learn about, teach, design, sketch, and map people, places, things, and patterns in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-Saint Paul.

______________________________________________________

References

Akagawa, K. 2009. Unpublished artist’s statement.

Cohen, A. 1984. herbert bayer: the complete work. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Inwood, M. 2000. Heidegger: a very short introduction. Oxford England: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. 1982. Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Makholm, K., et al. 2009. Paradigm Shift: Honoring Kinji Akagawa. Minneapolis, MN: Alumni Office of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

“News & Events: New Peace Garden Bridge dedicated.” October 7, 2009. Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board