Julie Snow Architects: High Modern Mediation

Julie Snow is working on a surprising and innovative addition / transformation of the Soap Factory's venerable and mossy environs. Here's Camille LeFevre's review of the book recently published by Princeton Architectural Press on her work.

Julie Snow Architects

Princeton Architectural Press

$40, 114 pages

Julie Snow is one of Minnesota’s star architects. This means she’s a modernist; a prerequisite to being included in this small, select group, which also includes Vincent James, with whom she once founded an architectural firm, and David Salmela, whose work is so distinctive it defines and occupies an aesthetic all its own. It means Snow’s projects consistently win awards from the Minnesota chapter of the American Institute of Architects (sooner rather than later if the jury is decidedly of a modernist bent).

It means she inhabits the realm of the local design cognoscenti, the movers and shakers shaping our built environment and increasingly design-savvy culture. And it means the first monograph of Snow’s work, Julie Snow Architects, has been published, at last. This handsome, smart compendium of 14 projects from 1990-2004, with clear and concise explanatory text accompanying each entry, is marred only by sloppy content editing and proofreading in two of the book’s three introductory essays.

The first essay, “Foreword: Heir Apparent,” by Thomas Fisher—dean of the College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of Minnesota, and author of the new book, Salmela | Architect—is a thought-provoking, referential evaluation of Snow’s place is the history of modernism. Fisher boldly begins by stating: “Julie Snow is heir to the Case Study House program…. a high point in modern American architecture.” The 36 Case Study houses, built throughout 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, he continues, “combined the social ideal of improving the lives of ordinary people through good design with the technological ideal of harnessing industrial science to minimize the materiality of buildings.”

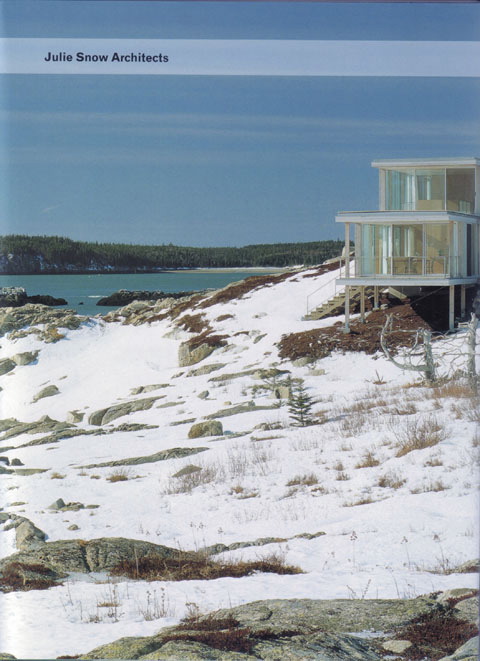

Fisher goes on to draw convincing parallels between various Case Study houses and Snow’s work, particularly the minimalist, glass-and-steel, light-filled industrial buildings she’s designed throughout the rural Upper Midwest. He also grounds Snow’s work in the Case Study architects’ “ethical stance toward modernism,” which integrated the “social idealism” and “economic realism” of many mid-century European and American modernists, respectively. “The Case Study architects pursued a pragmatic interest in programmatic and technical experimentation within the limits of what average families could afford,” he writes. “A similar pragmatism informs Snow’s work.” (One exception to that affordability, however, is the Koehler House, dramatically perched on a rocky promontory sloping down to the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick.)

In the monograph’s second essay, Snow articulates her methodology: how each job begins with the firm’s attention to and research into the “project’s unique programmatic, contextual, and constructional circumstances.” She articulates how “architecture becomes a point of friction, acting as the mediator between purpose and place,” resulting in design and construction that’s seemingly counterintuitive as it results (and herein lies her genius) in such intriguing innovations as thin, light, super-strong walls “achieved through a rigorous assembly requiring precise construction.” Too bad proofreaders didn’t apply that same rigor to the first paragraph of her copy, which is sprinkled with typos.

Snow’s pal Janet Abrams, director of the Design Institute at the University of Minnesota, penned the book’s third essay, “Julie Snow: The Rugged and the Refined”; a reverential, no, fawning mash note to her friend, whom she calls “the Emma Peel of architecture.” The essay careers from first-person description of speeding across the prairie with Snow in her black BMW, to the similarities between Snow’s architecture and Dutch still-life paintings “with their contradictory surface expressions of frugality and abundance”; from evaluations of Snow’s minimalism and “the states of calm that her buildings induce” to smatterings of the architect’s personal history; from background on the creation of particular projects to Snow’s entry into such offbeat projects as the SecurePet ID Collar and a Telematic Table proposed for the Walker Art Center.

Interspersed throughout Abrams’ text are unattributed blocks of copy, in smaller type but without quotation marks, that read as though they’re quotes from Snow. We’re to assume they are. At one point, Snow says of her firm, “We’re a little ‘techie’ at heart. I just really love construction—the way buildings are made—taking the assembly and refining it.” This statement is really what’s at the heart of this book, and Snow’s work.

Accompanying each of the 14 projects that make up the bulk of the 114-page book are brief narrative descriptions—of a building’s genesis, challenges, materials, solutions—and a clearly drawn detail (whether of a steel-truss wall penetration, a curtain-wall wind-frame section, an access-floor or roof-edge detail, or hood-enclosure attachment) that celebrates the art and functionality of technical detail in Snow’s work. Additional plans and sections, in combination with color and black-and-white photography, complete this monograph; a graphically fascinating book for design aficionados and architecture “techies” eager for a behind-the-scenes look into how-did-she-do-that? details rather than—as Fisher touched on here, but was much more generously able to provide in Salmela | Architect—in-depth critical evaluation and contextualization of Snow’s growing body of work.