Julia Durst: “Impromptu”

Suz Szucs reviews fellow artist and writer Julia Durst's show at North End Arts Gallery in Superior, Wisconsin. She finds the interplay between language and vision intriguing.

I know Julia Durst as a writer. That was my introduction to her, so when I happened upon her work at the North End Arts Gallery in Superior last month, I was pleasantly surprised. I was drawn to the work, it jumped out at me from the walls and immediately I recognized the active mind of a writer wrestling with ideas that can’t always be expressed verbally.

Being with Durst’s work is like being in a room with people who are whispering in a corner, but you can’t quite make out what they are saying. You’re curious, but strangely content; you want more, but are disappointed if the conversation becomes too clear. An impromptu is an improvisation, usually suggesting spontaneity in an instrumental piece. In looking at Durst’s work it is important to let go of the specifics and tune in to common experience. Like an impromptu, the work is ingenuous, it starts from a place of personal interest and the ideas grow from there. Her method creates complication and ultimately the work becomes about how we relate (or not) to each other, to the world, and how we put on many guises in doing so.

At first glance, one might relate some of Durst’s work to horror vacui, an unrelenting urge to fill space. Literally, those who suffer from this illness have a fear of emptiness and must saturate every square inch of the page with marks. I don’t mean to imply that Durst’s work demonstrates this compulsion; rather, the fullness of her marks upon color upon text or shape suggests obsessive activity or curiosity.

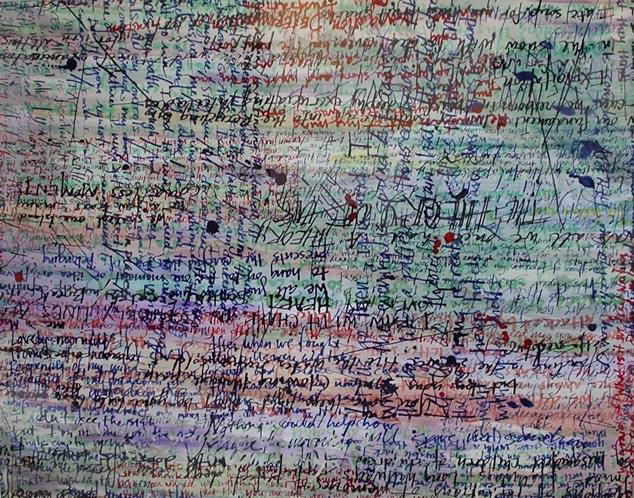

All Durst’s work uses layering to a certain degree and this is what provides visual interest to the viewer. Her layers create cacophony; they give sound to the pieces, especially when she’s using text. It is as though the layers represent different voices; by using line or symbol as well as text, she creates an impression of sounds given tonal variation by the color she balances the line with. Her text functions like automatic writing. It doesn’t seem important for one to have to read the words; rather, her titles give the viewer direction – a touchstone for how to approach the piece – while the writing itself is about the act of communication.

“Theory of Us” uses several different styles of writing to create an image that suggests the difficulty we all suffer in trying to communicate within a relationship. All of her text pieces present this concept: the impossibility of getting a message across with accuracy. Even “Declaration,” based on our famous founding document, becomes about the volatility of interpretation. Cultural change creates a need to re-decipher, with the meaning of the words shifting in relation to time and context.

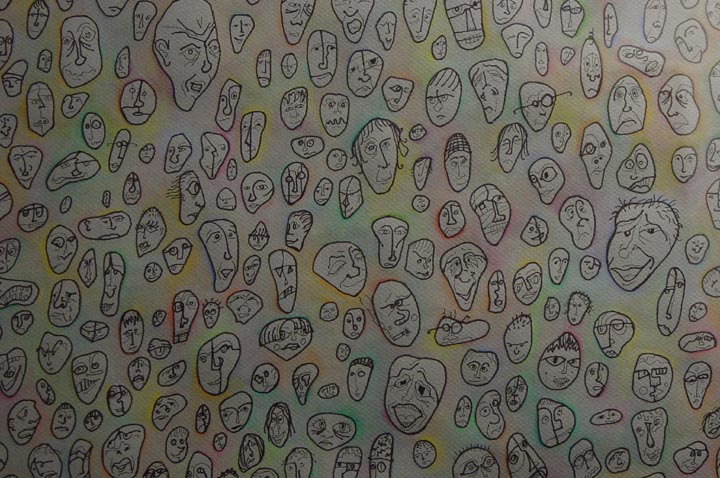

“Alter Ego” uses small drawings rather than text to address a similar multiplicity of viewpoints. Full of caricatures, it’s fun to look at and demonstrates skill and playfulness. But all the faces on the same level and self-contained is too literal an arrangement. It loses the other works’ complexity.

This problem doesn’t occur with Durst’s line drawings. “Filtering July” is the most successful of these, one of her more controlled drawings, with graphite lines forming bubbles drifting over cones of color. There is a sense of space here advantaged by layers without giving preference to the topmost one, as most of her text pieces do. The image opens up playfully. The text pieces, by contrast, are so frontal, their colors running and dripping paint, that they feel a little desperate – like the connection will never truly be made. The line drawings feel hopeful – celebrations of visual communication.

“Spin Doctor” is the only figurative piece of the group and is working quite differently, although Durst’s desire to explore multiple viewpoints is present in the four disparate versions of the same image. The images compete with one another, challenging the viewer to compare and contemplate which is the most accurate representation of the truth. This idea is supported by her other pieces, but the approach is so different that it feels out of place.

The exhibition is full of so many possibilities that it’s hard to know where Durst is headed. Several of the approaches are interesting, but they vie for attention. Her use of color is dynamic but it’s her obsessive working and reworking the image to illegibility that describes so well the inefficiency of human interaction. This technique breaks down when her symbols become too literal – faces and fishes – and is strongest when it gives the viewer a starting point for contemplation. Her best pieces are visual sound poems. These images remind us that language is not adequate for expressing all emotion and ideas, hence the need for visual art, music, and poetry. In a culture where artistic communication skills are often undervalued, Durst is trying to create her own visual vocabulary, using line and color in unrehearsed expression.