Inverting the Male Gaze

Sheila Regan assesses the Minneapolis Institute of Arts' multimedia exhibition, "The Sports Show," calling sports a surprisingly valuable lens through which to see the larger culture's changing norms and mores, particularly about race and gender.

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts recently opened the The Sports Show, an enormous overview of sports culture from the late 19th century up to the present day. While there are plenty of big name artists in the show — Andy Warhol, Gordon Parks, Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz, and Robert Mapplethorpe, to name a few — there are just as many, if not more photographs on view for which the artist is unknown. Many images included in this collection, especially the earlier work, portray amateur athletes, illustrating just how much the field of sports has transformed since their rise in popularity in America during 19th century. What was once something people do has increasingly become something people watch. The number of anonymous photographs included also reveals something about the evolving nature of the profession of sports photography, reminding us of a time when the subject of a photo was more important to the shot than the person behind the lens.

I must admit: before seeing the exhibit, I was skeptical. The very idea of the show seemed primarily intended to pander to audiences that would be attracted to the topic but who, ordinarily, might not attend a museum exhibition. A good idea for drawing new people in the doors, certainly — but would it work? And even if it did, would the results be worthwhile? Where does artistic merit fit in such a scheme?

Based on what I saw during my visit to the exhibit on opening weekend, there are indeed a number of sports fans attracted to the show, including children in team uniforms. Sports, it seems, are an effective draw for some, and kudos to the MIA for finding a way to bring those new audiences into an art museum.

It turns out, the merits of the show are solid, too, due in large part to curator David Little’s compelling thesis about the transformation of sports from a popular, participatory pastime to super spectacle. More than that, though, the work here offers a valuable lens onto the larger culture and new ways to think about discourses on race and gender, magnified and elucidated within the phenomenon of sports.

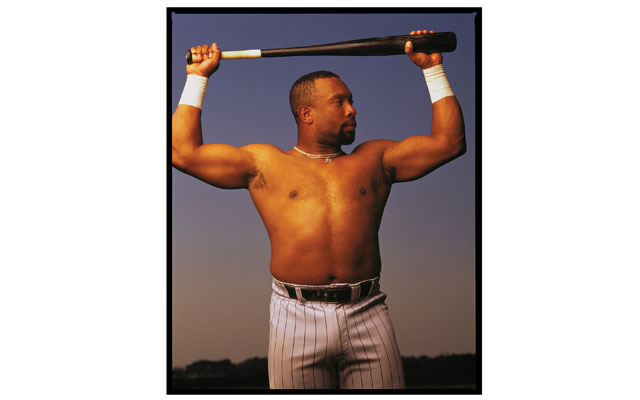

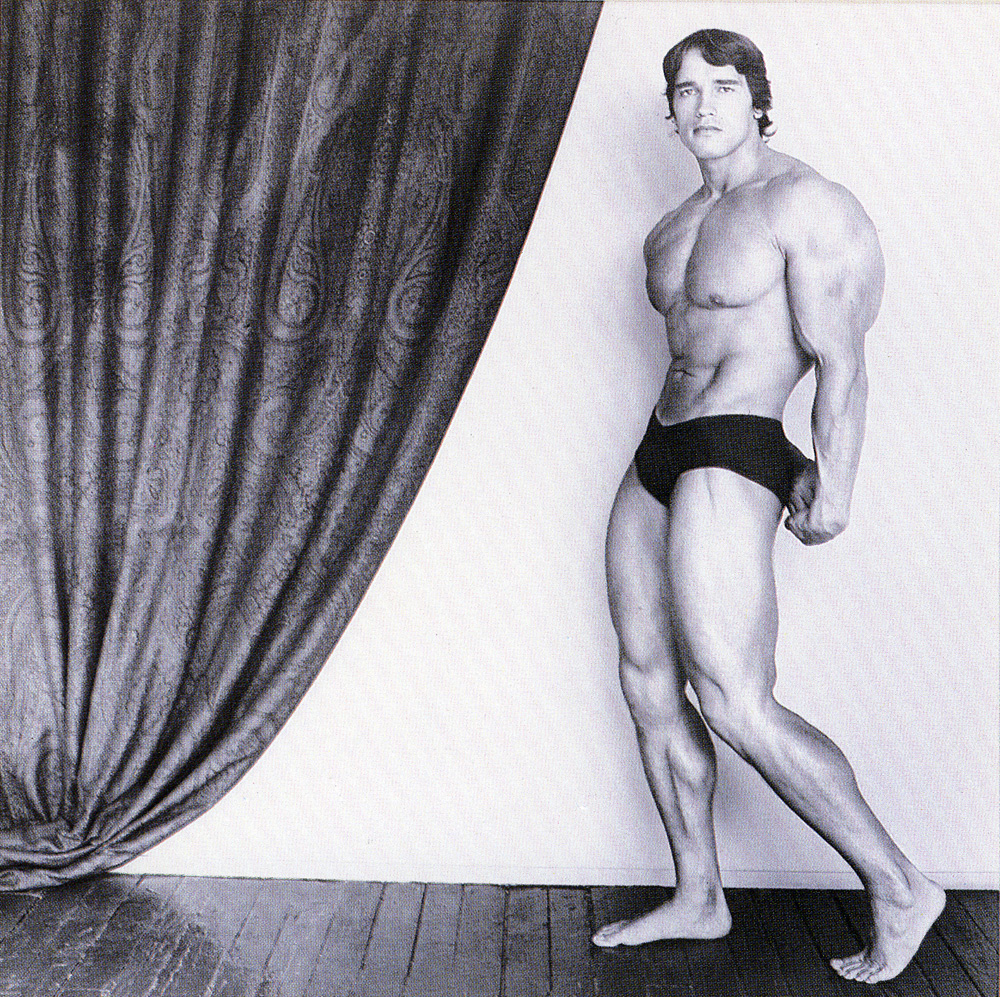

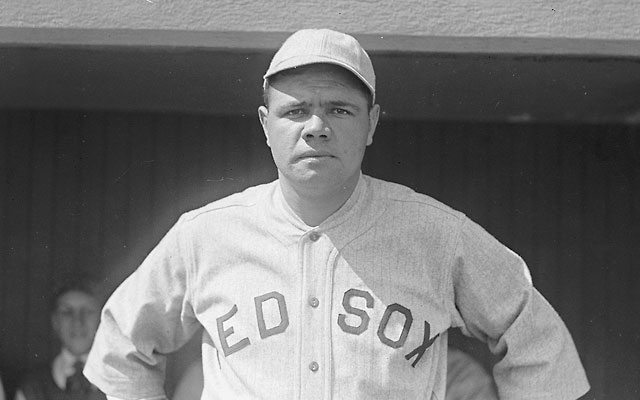

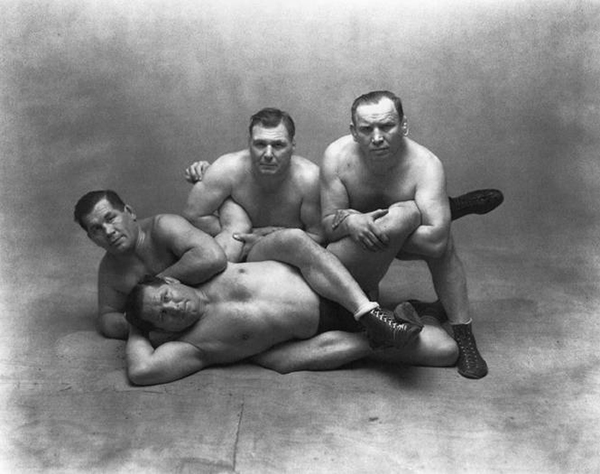

For example, while the female body has been the object of the “male gaze” for centuries, in The Sports Show it is not the female, but the male body that is primarily objectified (although there are images of female athletes in the show, too). In a portrait by Annie Leibovitz from 1988, Kirby Puckett flexes his muscles as he holds up his bat in Greek God-like triumph. And there’s Arnold Schwarzenegger, demurely clasping his hands behind his back as he thrusts his pelvis forward in a portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe from 1976. The Dusek Brothers, a wrestling family who gained fame in the 1930s and 40s, are positioned erotically (and somewhat comically) entwined in each other’s bodies in a bizarrely homoerotic photograph by Irving Penn from 1948. Besides these, dozens of other photographs portray male boxers, basketball players, baseball players, runners, etc., showing off their muscles and the pure form of their physiques, their strength and agility.

Perhaps sports, and by extension sports photography, offer a special dispensation for the indulgence of seeing the male figure as something to admire, or even to evoke arousal in the viewer.

Perhaps sports offer a special dispensation for the indulgence of seeing the male figure as something to admire, or even to evoke arousal; the images celebrate masculinity, aggression, and at times violence. Perhaps sports photographers are allowed to create shots in which the viewer is seduced by these athletes, because the images reinforce their subjects’ (and by extension, sports’) primal manliness.

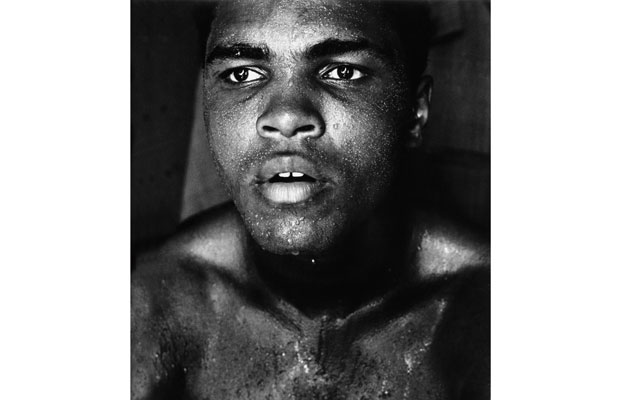

Curator David E. Little also includes numerous examples of specifically African American athletes as represented through photography, which together highlight an alternate sort of objectification of the male body through sports. Take, for example, Lew Alcindor, basketball player, New York by Richard Avedon. The lanky young man at the center of the image would go on to become Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, one of the greatest basketball players ever (as well as an actor, scholar, and cultural ambassador); Alcindor clasps the basketball in one hand, with his weight on one foot, looking at once strong and vulnerable. He wears high tops and his uniform, and he’s shown to be in a city park. Avedon’s image turns Abdul-Jabbar into an object of desire, but with an edge: his chin juts upwards and, in keeping with the stereotype of the “dangerous” black male, Abdul-Jabbar looks like someone to be feared.

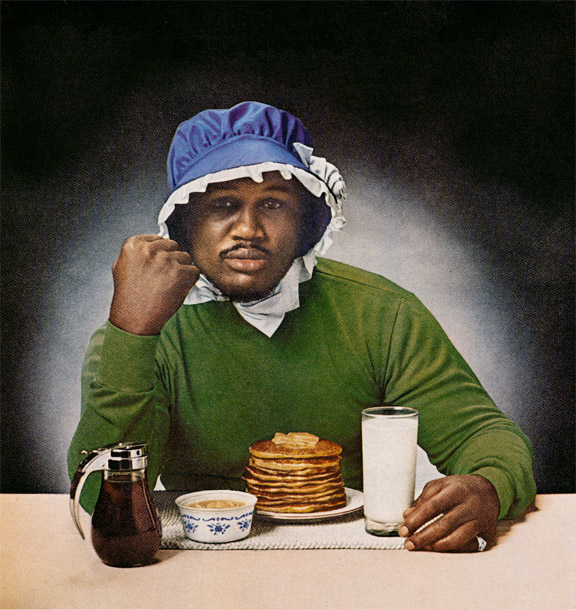

A fascinating segment of The Sports Show is Roger Welch’s O.J. Simpson Project, 1977. On one side of the installation, Simpson is shown being interviewed about his transition from football superstar to actor; on the other side, you see footage of sports fans watching a game. The fans, if not all white, are at least mostly white, and in the juxtaposition, Welch effectively makes a statement about race disparities in the world of sports — and he does so twenty years before Simpson becomes a national lightning rod for antagonistic race relations during his notorious trial. There’s still another provocative depiction of race in Hank Willis Thomas‘s Smokin Joe Ain’t J’mama: the heavyweight champion boxer Joe Frazier is shown with a blue bonnet and a plate full of pancakes. Taken from a 1978 ad for Blue Bonnet margarine, Thomas re-appropriates the image in 2008, pointing to its obvious reference to the Aunt Jemima archetype.

The photography in this exhibition spotlights the way politics, cultural norms, stereotypes and societal values all come to play inside the sports arena, a place where people of all different social strata have intersected in different ways throughout recent history. The show covers more than sports; these images reveal something about how we, as human beings, have historically viewed each other and how we interact and compete, as individuals and as global populations.

Related exhibition details: The Sports Show is on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through May 13, 2012. Ticket information: https://tickets.artsmia.org/public/show.asp