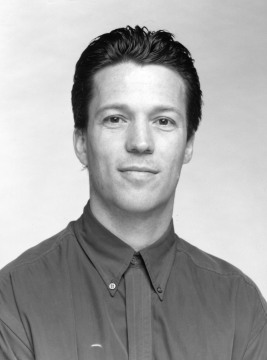

Interview: Out There with Philip Bither

Jaime Kleiman interviewed Philip Bither on the occasion of the Out There series at the Walker Art Center, an eagerly awaited annual festival of performance from around the world. Wondering why no locals? Read on . . .

When Philip Bither, 48, became the Walker Art Center’s senior performing arts curator in 1997, he announced no less than five new programming initiatives, all of which focused on expanding the role of contemporary performance.

This month, the Walker presents the 19th annual Out There series, a month-long event devoted to showcasing an international array of boundary-crossing artists. This month’s acts include the world premiere of Cynthia Hopkins’s Must Don’t Whip ’Um, a follow-up to her critically acclaimed 2005 Out There piece, Accidental Nostalgia; the London-based duo, Lone Twin, performing an ambitious work called Nine Years; playwright and performance artist Young Jean Lee’s Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven (a show about white people in love); and concludes with San Francisco’s Riot Group performing their newest work, Pugilist Specialist. (See the Walker Calendar for information on any of these performances.)

The following is excerpted from a phone conversation arts writer Jaime Kleiman had with Philip Bither on January 10, 2007.

When did you come to the Walker Arts Center and from where?

I came here ten years ago in April. Prior to that, I was the Artistic Director of the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts in Burlington, Vermont. It’s a multi-disciplinary center. Before that, I was the curator for the Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music [in New York].

.

How did you get into arts administration?

Arts administration is the general term. I think my area of expertise is in arts curating and producing. There are a lot of other terms—programming, directing, artistic directing.

With the Walker, I function similar to curators working in the visual arts or film and video…. I function as the primary programmer in the performing arts realm, which covers a lot of disciplines. I manage a staff of five people and interface with all the departments at the Walker. I sometimes co-produce anywhere from 40 to 70 arts projects a year from all over the world and sometimes from the Twin Cities, as well.

Did you ever have your own artistic aspirations?

Pretty early on, I realized maybe my strength was providing support and helping artists to achieve their own vision instead of creating my own work. That was as far back as college. I believe that everyone is creative. My outlet is in music on an amateur level and messing around with family and making things. During Thanksgiving this year, a lot of my family members came to my house, and in a folky sense, there was always a lot of people playing the instruments in my house. That’s always been a part of my life.

But I think my professional contribution has been in raising money and framing artists and figuring how to connect artists to audiences. My interest is really in contemporary forms—how do we reach audiences with what artists are attempting to do? That’s what Vermont really did for me, primarily working the artists themselves. I had to figure out how radical art expression could reach a community of regular people—not just artists—and [to] find a way for the Walker to find value in what the theatre community in the Twin Cities, in particular, does so well.

Why doesn’t Out There include local artists anymore?

We debate—consider—that every year. Part of that consideration is about what’s happening locally and asking what opportunities Twin Cities artists already have, and how a slot in Out There might serve them in the best way. I do feel like we are missing an opportunity now for local performing artists to have their work evaluated.

When we chose to stop having a local slot, it was due in part because we felt like it was an unfair set-up. Most of the work coming into Out There was coming here after years of performance on a tight schedule, and here we were inviting or commissioning local artists to do new work. But it was sort of an unfair set-up because audiences were comparing them against fairly established artists who were creating work and bringing it in already done.

The exact time that we stopped having a local component for Out There, we started the Momentum: New Dance Works series so that [locally made] experimental performance work could have an outlet. We are grappling right now with how can we have something like Momentum for theatre artists. Last year at Momentum, we had Live Action Set, which has one foot in the dance world and one foot in the theatre world.

Each year we consider whether there should be an RFP for performance and theatre artists—like with Momentum. Since Out There started, things like the Fringe Festival have grown, and Patrick’s Cabaret and Balls Cabaret and other platforms have emerged. There’s also Isolated Acts at the Red Eye.

But you must know that showing work at the Walker has much more cachet on a national and international scale than self-producing at smaller, less established venues.

I do know that. There is a glass ceiling. I understand. I used to produce in New York and it’s hard to get people’s attention. We regularly select tapes of new artists to take to conferences to tell people to keep an eye on local companies. A lot of that [work] is invisible. I know that sounds a little defensive, but we are trying to figure out how local work can get seen more and we are talking about them [to other producing organizations]. I take that responsibility seriously, but there’s a limit to what we can do well and where funding exists.

How do you choose the Out There shows?

It’s primarily by invitation. We have a long list of artists we’re keeping an eye on. Three of the Walker performing arts staff members and I collectively see 100+ showcases and performances a year. I do a lot of traveling and see as much as possible. I get to New York about six times a year to see this or that in a very short period of time. Plus there are arts festivals in Berlin and Edinburgh and Brazil and other places. I’m going to Torino, Italy, this weekend to see a show I hope we can bring in next year. It’s rare that I’ll fly out to see just one show, though.

To be honest, there are so many artists we have relationships with and hear about from colleagues and multiple networks around the country. A lot of times, artists are recommending other artists to us, too. We keep our eye out all the time. It’s a combination of press, recommendations from other colleagues and artists, and seeing as much as we possibly can.

This year’s lineup is work that’s coming from New York and San Francisco and England. It’s not [that these are] the four greatest pieces of experimental theatre, but it’s what we’ve found to be an interesting mix of new kinds of performance, and that’s what we try to do with Out There.

Are you the sole person responsible for the Out There programming?

I work with the advice of my staff, who have been working in these realms for many years. Nationally, there’s a good group of curators and producers who have created a network of colleagues, mostly at contemporary art centers. I think the Walker is viewed by most of these people as being there very early on.

Cynthia [Hopkins]’s piece got a great review in Variety this morning and will later tour to [many different venues]. That might have never happened if the Walker hadn’t given her two weeks in the theatre and a big chunk of the commissioning funds she needed, and be the first one out of the gate to present the work.

Why do you think there is reluctance in this country to produce experimental and collaborative work?

There have been books written about this question. It’s very complicated. I think it has something to do with the fact that the live arts have always been tied to commercial interests in this country. There has been very little distinction between entertainment and live art or art that runs in real time. This is not to say that experimental theatre can’t be entertaining or wildly inventive.

There’s a very small amount of public support for art here, compared to Europe and other parts of the world. It’s forced a great deal of work in America to appear primarily in commercial spheres. That’s one aspect of why there isn’t more of a willingness to look at innovative approaches to live performance in America. That’s the first thing that comes to mind.

Sometimes I think the [American] media has the tendency to create categories for artists and artwork. I always laugh to think that what the Walker does in the performing arts world is described as wild or experimental. It’s not.

How do you define “experimental”?

I define “experimental” as work that is attempting to carve out new ways or hybrids of creating live performance experiences. Experimentation happens in all forms of the arts, but the most exciting realm is when those disciplines come together in new ways. How do you force disciplines to create a language together that may have not existed before? You can always argue that there’s nothing new under the sun and much of what we call wildly avant-garde probably already happened…but I think new technologies like the Internet and television keep pushing art forms into new directions.

For me it’s about a spontaneity and a newness that commercial constructs and replicated performance can’t allow themselves to do. In the theatre realm and in the performance realm, this is on my mind a lot: what’s the point of theatre?

I love working with the artists and being exposed to new ways of thinking, and being delighted with things that creators are coming up with that I would have never dreamed possible or imagined. I spend many sleepless nights trying to figure out how to get some of what I think is the most vital work in the world onto stages.

Out There 19 runs through January 27. For tickets call 612.375.7600 or buy them online at walkerart.org/tickets.