Interview: Ana Lois-Borzi Talks About Urbia

Patricia Briggs spoke with Ana Lois-Borzi about her show inaugurating the new Thomas Barry Fine Arts location, at 530 N. 3rd Street in Minneapolis. Ana is pursuing the quotidian city, it seems. See the show through October 21.

Patricia Briggs: Ana, could you say something about the title of the show, “Urbia”? It has connections with the word “suburbia” but does it have further meaning for you? Was I on the right track when the work brought to mind associations like “urge” and “burp”?

Ana Lois-Borzi:Actually, these are very good associations, but I didn’t think of them.

I was thinking of urbe, the Spanish word for city; as a self-contained environment…like a medieval town. I was thinking of the exhibition as a space, where each part had to talk or to be able to interact with the others, where you could draw lines from the individual sections and in between them. So it’s like its own citadel of meanings.

PB: Is your work here some sort of institutional critique or is it more the manifestation of a personal vision? Or is it these two things together?

ALB: Um, let’s put it this way. If there is an institutional critique here it has happened as a byproduct. It wasn’t originally conceived in this way. … It would be a product of the process.

PB: To clarify that point . . . .would you say that the institutional critique would reflect on issues of gender?

ALB: Yes, gender, sexuality, subject positions. The discourse of alterity and the construction of discourses on and about subjectivity.

PB: About identity, but not identity politics? Is it about identity in a more psychological or psychoanalytic way?

ALB: The problem with identity is that it can get very essentialist and that is not at all what interests me. For me identity is not fixed. It is an ambivalent space where you can inhabit oscillating positions. Where you can see yourself in and out of them simultaneously.

PB: Let’s talk about this issue of the personal. This work seems to come from a specific perspective–which is your own, and the experience in the world you currently inhabit.

ALB: Yes, I just want to acknowledge that this is true. That space is the space of the female subject in representation. I’m trying to open it up rather than make it the space of Ana in the world.

PB: And how about the issue of motherhood?

ALB: It is here and it is present.

PB: But it is not “in your face.” I like this idea of opening it up and not essentializing it. The way that you deal with motherhood and woman-ness reminds me of Janine Antoni. In her work she is able to address things like the “care of another” and “human touch” in a way that is much bigger than this little patriarchal category “motherhood.” I feel this kind of opening up happens here.

ALB: Thanks.

PB: I think that one of the most challenging things about your work is the prevalence of found objects. There aren’t many artists locally who work with found objects to the extent that you do.

ALB: Well, there are a few, like Aaron van Dyke, Suzy Greenberg, and Joe Smith.

PB: But they modify them more than you do. In your work the found objects retain their identity more than they do in theirs. Why do you use found objects? What are you doing with them?

ALB: To start, I don’t think there is a thing called a “found” object. Meaning, nothing is truly found. Everything has been made. Even when you are working with colors and a canvas you have chosen that red that you are using and it has been made. Even if you mix it with another red you are still mixing two reds that have been pre-made. No one is working from scratch. It has all been made already by nature or by other processes. “Found” as such, is a category that does not exist.

So…I am using these things in the world. Some are more object-like— [pointing toward the piece Italo’s Poubelles, which incorporates two trashcans]—some are real discrete objects. Completely shiny, manufactured, stainless-steel objects. I thought of actually making them myself. But I would try to make them exactly as they were. So what’s the point?

PB: By keeping the real thing, you keep all of the desire that is involved in our desire to have and consume them. The desire that drives the person that designed them—the trashcans–which is all tied to hygiene and desire to keep our bodies and homes clean. So you retain all of that when you use the already manufactured thing.

ALB: Yes, I think so. And then the other part is that I think of these objects as one could think of tools or using a crayon instead of charcoal pencil. They’re all things that we use. They are all out there. Everything can potentially be integrated. So there is no difference in a sense in using something that somebody else has made if you can conceptualize the object as your own articulation.

PB: Speaking of found objects . . . these hand-made crochet blankets that you use in this floor piece are astonishing. You must have gotten them in second-hand stores. They represent so many hands working, so many hours of work, and so many gifts given. It’s amazing.

ALB: Yes, they are so incredible. They are so encoded. Usually when people give them away—as they are making them they have the person who they will give them to in mind–an environment, a person, and a function. They are making something that is so laborious, while making it their life is happening, it is being interwoven into the crocheting of the blanket. You know, it doesn’t take an afternoon; it takes weeks. … We think of the old lady who is crocheting. Each being has importance and each being is producing something real in the world.

PB: The person who is doing that weaving is the mother, or grandmother, or sister…

ALB: It’s usually a woman. I have a hard time seeing a male crocheting. I know that some men do but I don’t think they did these. In my imagination they didn’t.

Another thing about the found object is the desire that is embedded in the object itself. And when you acquire the object that you want you are in the midst of a narcissistic identification with that object.

PB: Why do you call that a narcissistic identification? Is it that you somehow see yourself in the object? Is the object a text to project yourself onto?

ALB:

Yes, it’s a kind of mastery done by the ego. The things that we desire, why do we desire them? We are projecting onto them, right? And if you acquire them, somehow you gain power or mastery over the splits and gaps that your being has. So you incorporate them into your ego.

PB: But is it the trashcan that is right for me? Or the one that makes me feel more whole…

ALB: …Or the one that makes my kitchen cool. Or is it moms in suburbia talking about trashcans… I mean you can spend an afternoon with moms and their toddlers and inevitably you will end up in the kitchen commenting on trashcans. It might get to the point where they will admire your freaking trashcan. This is real. [Laughing]

PB: In your Franklin Art Works show two years ago you were using stuffed animals. They seem mostly to be gone now.

ALB: Actually, they are gone but they are present…. Those two could only have happened because of them [pointing toward two dolls’ heads used in the piece Two Little People and Likely, which is made of large fabric letters stuffed like pillows].

PB: In earlier exhibitions of your work I have seen you use words and stuffed animals in the same piece, placed next to one another. In Likely they came together in a more seamless and successful way I think.

ALB: Yes both things are one here, rather than one and then the other.

PB: Can you say something about this word, “likely”? It’s an odd word.

ALB: Yes, I’ve been thinking a lot about the potential of things. I get really excited with how many things can potentially be. Like immanence and becoming in a Deleuzian sense. I get all tripped up about the potentiality of things. But in actuality not all potentials…come into being. So there is that difference between the potential in possibility and the actual. So my question to myself is: potentially this is great, but is it likely? Conceptually everything is potential, is possible. But is it “likely”?

PB: So “likely” is a slight narrowing?

ALB: Yes, it’s more realist perhaps—a reigning in. Potentiality is incredibly exciting. But from potential to actual being—is it “likely”?

PB: What about the drawings? In the past you have tended to mix drawing and found objects in the same piece, as in collage or assemblage. Here they are separated—the drawings are in frames and set off from the sculptures—yet they seem to be in dialogue in some way with the sculptures. Still, it might be hard for people to see how they relate. Can you say anything about their relationship?

ALB: Well, what do you see in the drawings?

PB: The drawings seem to be about becoming—again in a Deleuzian sense of endless unformed potential and possibility. It seems like an automatic process, like the Surrealist idea of automatic drawing. I sense the formless here, the irrational formless as opposed to the rational formed. Yet there are places in the drawings where recognizable objects—glimpses of toys, baby bottle nipples, penises —appear, these are things that have to do with the body. All of this seems similar to aspects of the sculptures, yet the drawings don’t look like the sculptures.

ALB:

The drawings and the sculptures are linked. But they are not preparatory sketches or studies for the sculpture. They are co-inhabitors of a similar psychic space. It’s the same mind-frame. I work on them all at the same time. … The drawings took a very long time to produce.

PB: Really? That is surprising as they are so understated.

ALB:

Yes, exactly because of that they take a long time. I had to respect them. I had to go through a process of acknowledging their own voice and letting them be. Trying not to control them and over- impose on them a voice of mastery. And that takes a long time. … When are they done? When are they ready? When are they overdone and I have to go back and erase, and even when the evidence of the erasing becomes part of the work. … In all of them I erased a lot. Most of the time you don’t see that… It is only late in the process that I impose that kind of editing.

PB:

How would you describe or theorize this process of drawing? Is it self-expressive?

ALB:

In terms of process…it is not about “self” as in “self-referential”… at least it isn’t at the beginning. … They come from me but they are not an investigation of my psyche.

PB: What, then, are they an investigation of?

ALB:

That space theorized by Kristeva as the chora. They are about the process of becoming their own thing. …The unveiling of a who that I also am yet that doesn’t inhabit my consciousness.

PB:

Some feminist theorists would call that l‘écriture feminine.

ALB:

Yes, that is the territory that I’m exploring. And this echoes too in the sculpture. That is why they can be placed together.

PB:

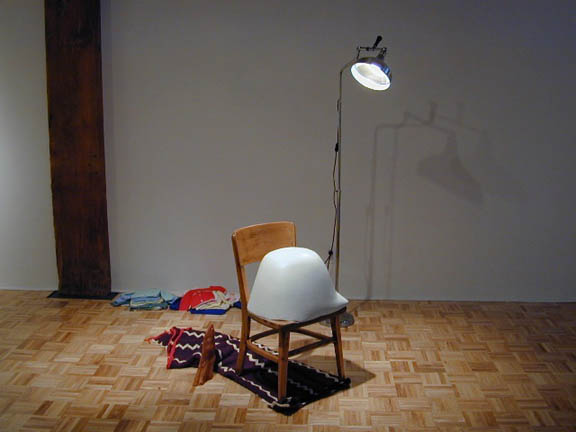

It Came to Shove seems like the exhibition’s centerpiece. As I see it, the metal lamp and the austere wooden chair represent some sort of institutional disciplining function—like medical or educational disciplining of the body. The little infant sweaters suggest an early stage of childhood development—possibly the shift from Lacan’s Imaginary to the Symbolic phase where identity is interpolated by intuitions like language, kinship, and gender. The strange plaster lump is shown as if in a state of becoming. Am I on the right track here? Could you elaborate or counter my reading?

ALB:

There are many tracks of interpretation… and you chose really good ones and each of those tracks can go further too. They are all possible and all likely [laugh]. What I would add is an intersection of the lived body, or better the embodiment of lived experience. For example, the cultural specificity, socially determined subject positions. The female in this …this piece is absolutely gendered. As I was making this plaster form, I was bending over it and going in this circular motion around it. … It was so sensual and sexual and it became a clear signifier….

There are different subject positions for interacting with this piece even for myself. The institution, the iconic and debased, of motherhood . . .

PB:

Do you think it is possible to read this piece without theory?

ALB:

Well, yes. At the opening, for example, most people chose an item in the piece and we talked about the making of that item, or babies and children. It was interesting. I really believe that anyone with any artwork can position himself or herself in such a way as to be open and experience the piece–to allow for a becoming, or vulnerability, or a not understanding, or a rejection. Whatever it might be. But there is the potential for connection in the piece whether the piece is good or bad. If it is something you understand or not the potential is always there. Do we make it actual? Often we are hurried and don’t have the time or we are too busy in our heads.

PB:

…Or we have preconceptions or desires for what art should be like. Like beauty, for example.

ALB:

Yes. With my work, I am not going for formal beauty. It isn’t that type of work. If it gets to that it’s great. But it’s a byproduct. There are multiple audiences, and multiple readings even within one person.

When you go to see a movie, no one tells you how to interpret it. Even if you say it sucks. That is a great reaction. If someone is truly interested in the film or in my work, they might read something more and explore it. Or someone might want to meet afterwards and talk about it. But not many people do that.

PB:

Is it that we aren’t trained to do that with art?

ALB:

I think of contemporary music. Young people write about it as if they know everything about the entire history of music. But no one feels like they can do that with contemporary art. I don’t see the big difference. People write reviews on music all over the place, and I wonder why don’t they do that with art? Maybe it is that with art we haven’t transcended the opera stage.