Inside the Cabinet of Wonders

An engaging essay by Andy Sturdevant on the perennial lure of strange and beautiful objects, written in honor of mnartists.org's inaugural ARTmn exhibition, "The Precious Object", which opens September 18 at the Hennepin County Library in Minneapolis.

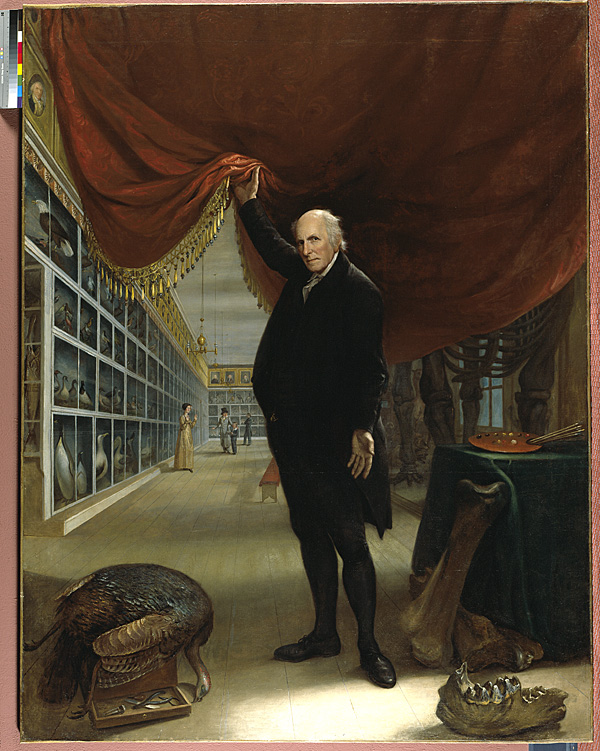

If we are going to talk about precious objects in America, there is perhaps no better place to begin than with a painting that hangs in the museum of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts: Charles Wilson Peale’s 1822 self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. You may recall it (the painting and the museum) from college art history surveys. The painting is one of Peale’s last major pieces, and the museum it depicts became his life’s work.

Peale, soberly dressed in a dark suit, stands center-front in what seems to be a fairly standard portraiture setting, before the sort of red velvet curtain that so often serves as a backdrop in these types of paintings. But wait, there’s more going on — with one hand, he has lifted the curtain, and with the other hand, he makes an understated “behold this” sort of gesture. Behind that curtain is a cavernous hall stretching off into the distance, stacked floor to ceiling with paintings, taxidermy, skeletons, and what today would be known as dioramas. Several figures in varying states of contemplation populate the space.

Charles Wilson Peale was known primarily as a painter; but here, he has abandoned his palette and brushes, laying them aside on a table next to him. “To hell with oil painting,” he seems to be telling you. “I have a mastodon in here.” As if to prove his point, one of the figures in his museum, a woman in a high-waisted golden dress, is caught mid-gasp, throwing her hands up in amazement as the curtain is opened. Shocked and delighted, she beholds the mastodon in question, the bones of which Peale and his team have re-assembled in three dimensions on a frame. “Oh my goodness!” she seems to exclaim. “That is a mastodon!”

In the portrait, Peale bears the unmistakable, stately look of a man who takes his collection seriously. And so he did: his museum was one of the first to categorize natural materials according to contemporary notions of taxonomy. However, there is an undeniable undercurrent of showmanship in his presentation-an element of what would later be termed razzle-dazzle (a very American coinage from the dawn of vaudeville). With his painting tools set aside, Peale’s art is now the acquisition and arrangement of objects for the viewer to behold. The other figures Peale has pictured in his museum may be contemplative, but not the woman. Her reaction to what she sees demonstrates that, even during the Enlightenment, with its Linnaean taxonomy and rational worldview, there is still a prominent place for wonderment when considering the material world.

As traders, seafarers, and soldiers returned from Asia, the Americas, and Africa with never-before-seen artifacts from those lands, and as scientists, artists, and philosophers in Europe began exploring new ways of understanding the world, there arose a demand for the most remarkable, rarest, and most exquisite examples of, well, everything.

The objects Peale collected and displayed – everything from “Persian armor and clothing, &c.”, letters by Franklin and Washington, wax figurines, and engravings of the human ear, to cases of coral, stone sundials, and “frames containing Lenses and specimens of Minute Writing” — were both natural and handmade, and frequently at the intersection of the two. Natural history, craft, fine art, biology, medicine, engineering, philosophy, cultural history, illustration, anthropology, and even performance all bleed into one another with little regard for formal disciplinary boundaries.

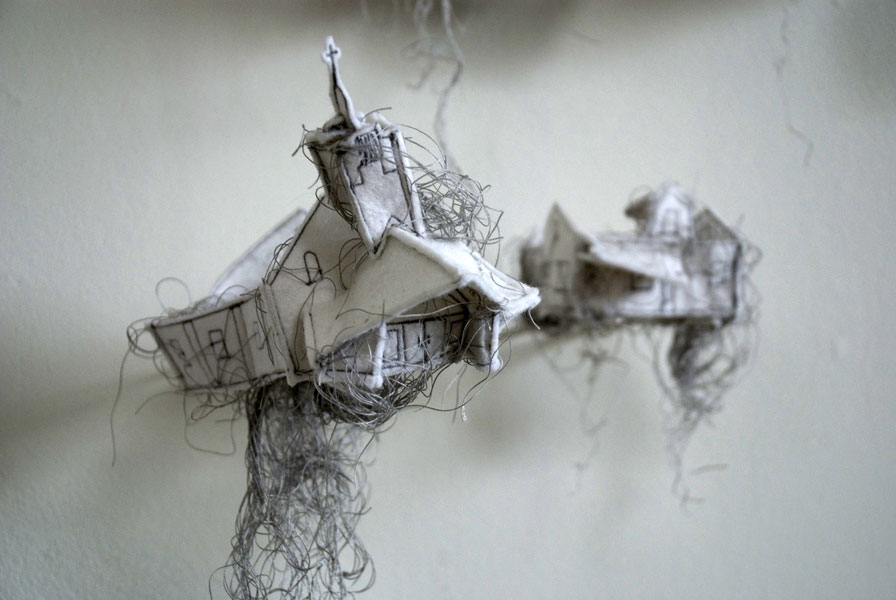

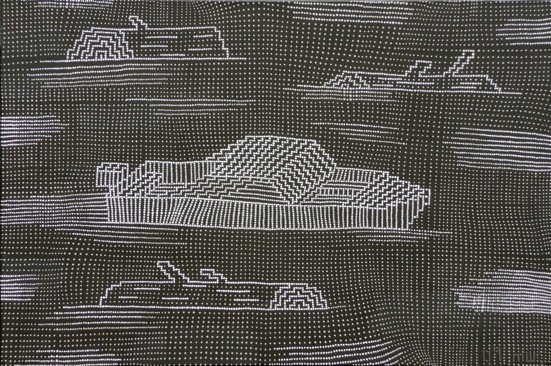

It’s fitting, then, that The Precious Object takes place in a public library. Up to Peale’s time, there were few distinctions made between public and private venues for viewing precious objects, or how they were presented. The forerunners of Peale’s American museum were Wunderkammern, “cabinets of wonder.” Wunderkammern — the “cabinet” often referred to a full-sized room in this context, though sometimes an actual piece of furniture — began appearing in Europe during the Renaissance. They were not quite museums, not quite sideshows, not quite dioramas, not quite reliquaries, but some combination of each of these. Primarily, they were manifestations of the sudden outpouring of humanist curiosity and imperialist bravado that were bursting out of Europe during the early Enlightenment. As traders, seafarers, and soldiers returned from Asia, the Americas, and Africa with never-before-seen artifacts from those lands, and as scientists, artists, and philosophers in Europe began exploring new ways of understanding the world, there arose a demand for the most remarkable, rarest, and most exquisite examples of, well, everything. A miniature painting, a piece of coral, the jawbone of an elephant, a mummy, antlers, Chinese porcelain, and a rare coin might all coexist in the same space. Such assemblages existed both to dazzle and to edify, to prompt both contemplation and wonderment.

These collections might also be known as a Kunstkammer — “art cabinet” — though only some of the artifacts on display would meet our contemporary understanding of “art.” Indeed, so many of the natural historical and scientific elements included were forged or exaggerated, that a certain degree of human aesthetic ingenuity inevitably entered the picture. The idea was that, in the Wunderkammer, the world was recreated in miniature and perhaps, in some way, controlled or at least better understood, through the gathering and arrangement of these objects.

It is with Peale’s Philadelphia museum that we begin to see the opening of access to these collections to the viewing public (for a price, in his case — the concept of free admission in the interest of civic improvement is not one that comes along until later in the 19th century). More importantly, in Peale’s museum we also see the beginnings of separation of the sensational (mummies, unicorn horns) from the more verifiable (fossils, art pieces, mounted animals). In American life, however, the continuum between credibility and hucksterism has always been a short one. It’s telling that when Peale died, half his collection was purchased by P.T. Barnum, the greatest huckster of them all. Fine art began to go one way, natural history another; science one way, entertainment another.

But the circus sideshow, the contemporary art gallery, the science museum, even the curio cabinet in your great-aunt’s drawing room with the Franklin Mint commemorative plates — all of them are directly descended from a common ancestor. It’s a genealogy we can trace through the objects that people have taken the care to find, assemble, create, and contextualize. The spirit of The Precious Object draws back to that early impulse from the dawn of the contemporary age – an interest in bringing together a group of objects in one place to find out how they interact with one another across disciplines, and to discover what narrative threads about the world they tease out.

Peale’s interest in creating his collection was principally to help the viewer understand the world in a rational, ordered way. However, there are always those objects that inspire in us, the viewers, unadulterated wonder; we’re like Peale’s museum visitor in the high-waisted golden dress, throwing up our hands in amazement and delight.

Exhibition details:

The Precious Object, mnartists.org’s 2009 ARTmn exhibition, opens at the Hennepin Country Central Library in Minneapolis on September 18 (reception from 6 – 9 pm). The show will be on view through January 3, 2010.