Indians and Indians: Kathak and Fancy Dance

Katha Dance Theater and Native Pride Productions created a startling amalgam of two ancient traditions. Lightsey Darst does a beautifully tough-minded account of the experience of seeing it.

Katha Dance Theatre and Native Pride Productions, “Dots and Feathers,” was performed at the O’Shaughnessy late last month.

Lately I’ve been troubled by the thought that a good chunk of dance criticism is simply genre recognition. That is, you use certain cues to figure out what genre you are looking at, and then, armed with your knowledge of this genre’s techniques and aims, you assess the choreographer’s and performers’ ability to excel at this genre. Are the dancers wearing pointe shoes and tutus? It’s probably classical ballet! Now look for pointed feet, straight legs, upright bodies, etc. Read a traditional ballet review and you’ll find that each performance is held up to performances from the past, each dancer held up to the dancer who originated or excelled in that role—and all this depends on the reviewer’s knowledge of the genre.

If that’s all reviewing is, it certainly is a sad pursuit. Moreover, if that’s all reviewing is, there’s no way a reviewer can wander outside the confines of genre-obedient dance forms (say, into the free fall of avant-garde dance), or outside the confines of the reviewer’s knowledge. There would be no way for me, for example, to comment on “Dots and Feathers,” a production bringing together Native American and Asian Indian (specifically, Kathak) dance forms, neither of which I am very familiar with. And yet that is just what I am about to do.

Clear the decks! Hold onto your hats! This should be interesting. . .

Do I have any idea what is going on?

No. I enter and the Indians and the Indians are already milling around on stage, making me feel out of place. I run into an immediate note-taking problem in distinguishing the two groups—the linguistic confusion that got Rita Mustaphi of Katha Dance Theatre and Larry Yazzie of Native Pride Productions collaborating in the first place. I’ve got a more serious problem too, in that I don’t know what it means to engage in worship dance, which both of these dance forms claim as a background. I don’t know how to deal with artists aiming their dance upward (outward, downward—different gods reside in different places) in the context of a concert dance performance, where the expectation is that the dance will be aimed at me. I don’t know how much I can rely on my normal ability to determine whether something is dull, well-made, well-performed, etc.

More specifically, I know a little about Kathak (a storytelling dance form, with heavily rhythmic footwork and a certain repertoire of meaningful gestures and expressions) and have seen it before, but can’t claim to be an expert. I have never seen Native American dance before at all.

Can I criticize it?

Sure. I can say things like, “The Kathak section was too long.” I can say, “The sound was too loud.” If I say, “The incessant prettiness of Kathak, particularly the simpering prettiness of the women, grates on one after a while,” then I am in dangerous territory (particularly if I use the pronoun “one”). And yet that’s how I felt. But I didn’t see that treacly sweetness from all the female dancers, or in all the pieces—some had a delicious goddess-like sharpness, even to their smiles—so perhaps I can chalk up the overload to the choreographer or to individual dancers rather than to the form itself.

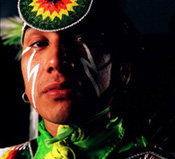

The Native dances I wasn’t inclined to criticize. Everything fresh is exciting: I liked the hypnotic simplicity of the jingle dress dance, I liked how in the fancy and chicken dances the arms and legs, bowed out and adorned, seem like equivalent limbs. And this brings up the flipside of the above question: Can I praise it? For all I know, an authority might quibble with Lee Goodman Jr’s chicken dance; I wanted more. I liked how Larry Yazzie kept all his complicated streamers and feathers aflutter in the fancy dance; I liked the elegance tall Jocy Bird brought to her wildly spinning shawl dance.

Is “cultural dance” boring?

Those of us used to modern or avant-garde dance and art have become accustomed to being unsettled. We expect that a work of art should present us with some new idea, some critical thought (and we place a gold frame around that phrase “work of art”). We critics sometimes feel that our job is to ferret out that critical thought and bring it to you on a silver platter. All of us expect that art should change us. Next to our usual fare, will “cultural dance” be like grandma’s quilt next to Philip Guston—just somebody else’s grandma’s quilt?

First, it’s worth noting that all dance is cultural dance. Modern dance is a Western cultural dance, as is its brat-child avant-garde dance. But this sidesteps the question, which is really, are these dances from other places going to deliver the mental challenge that I like?

No, and yes. If you don’t pay close attention, it will all flash by, a lot of brilliant regalia, leaving you with nothing. Kathak and Native dance are not trying to deliver the particular frisson so beloved of Western artists and audiences (at least, not in their original form). But if you do pay attention to what is there, if you question, if what is there is genuinely something other and not a heat-lamp version of the other delivered for your Western palate, then you are bound to find something.

The Native dances seem fairly simple, by which I mean that just a few characteristics set each dance apart from the others, and within each dance there do not seem to be so many different steps. Five minutes of fancy dance is a lot like one minute of fancy dance. And yet put five or six different Native dances on stage at once and you have a picture of the world—a vision ultimately more various that that which the complex Kathak provides, for in Kathak (as in ballet) each dance clothes and moves the dancer but does not try to change the fundamental ideal of nobility that the dancer projects.

My mind balked at the diversity when all the Native dances went on at once. The edge of a Weltanschauung hove into view: how things move as a category of prime importance, a measure of identity. . . So there’s a frisson for you. It was harder to get at than the usual shuffling of elements of the familiar world, but it was there to be had.

And the upshot is. . .

Recognition-criticism certainly has a purpose. I like it when Alastair Macaulay of the New York Times educates me on ballerinas and their roles. The knowledge that comes from a lifetime of viewing is priceless. And yet, in so far as the critic’s experience is an amplification of the audience member’s experience, recognition-criticism is a hard row to hoe, leaving one confined either to a few dance genres or to endless hours in the library. It must be possible for audiences and critics to view and think and talk about dance that is not familiar. After all, at some level nothing is familiar and everything is its own genre. The question is how. This is a grammar of response not yet widely known.

“Feathers and Dots” relies on audience goodwill (abundant at the opening) to hold the performance’s various strains together. Asian Indian and Native American dances do cast light on each other, as any two objects held up together tend to do, but the collaboration between Yazzie and Mustaphi has not yet advanced to a more illuminating stage. Mostly, I noticed that Kathak is far more presentational, while the Native dances felt more internal.

Watching Kathak, I felt myself in the grip of the emotions of traditional stories: admiration for strong, beautiful, and virtuous heroes and heroines, anxiety over their conflicts, exhilaration in their triumphs, pity for their defeats. I felt also that the dance meant to make me feel something. The Native dances simply are; they didn’t seem to need me. They could have been more difficult to enter than Kathak, but I was in the right mood to be caught up in their directionless being.

It’s a start.