In Review: Face of the World

This review digest from the current issue of "10,000 arts" contains excerpts of articles relevant to our theme of world art. Click the links to read the full texts.

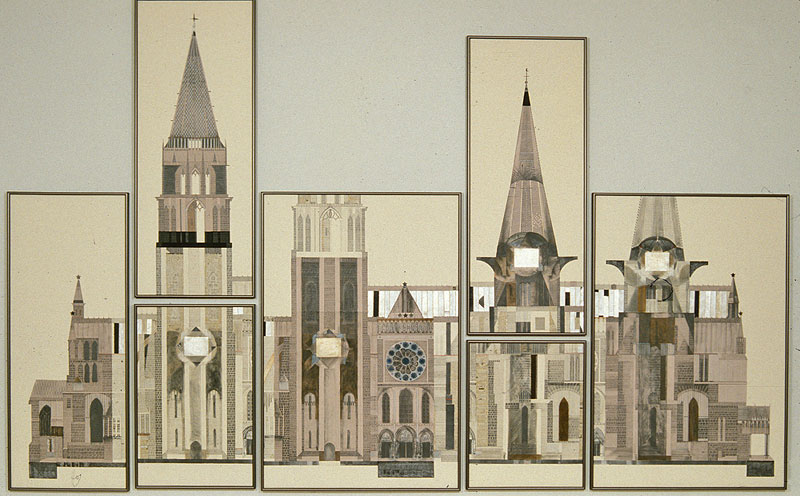

Mary Griep at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts

July 30, 2007

Michael Fallon

Michael Fallon writes on Mary Griep’s large drawings of ancient sites from Mexico, Europe, and Asia.

Consider Mary Griep’s work. It begins with wishfulness from the very beginning—its title, “Anastylosis,” is a reconstruction technique in which a ruined archeological monument is restored after careful study by using original architectural elements whenever possible, as well as supposition and guesswork when necessary. No matter how rigorous the study, errors in reconstruction are inevitable and original components will be damaged.

But I like the idea of analstylosis—the glorious and beautiful hubris of the attempt to reimagine and recreate—because it’s the only way we can even begin to realize unknowable mysteries.

In Griep’s work, this wishfulness reveals itself in the impossible and highly obsessive-compulsive charting—brick by brick, cornice by cornice, mosaic tile by mosaic tile–of one version of the ruined sacred spaces, temples, cathedrals, and other monuments of the past. The finished works, inevitably flawed, proudly wrong, full of absolute humanness, are beautiful for the imperfection inherent in their execution. They are charts of futility—mapping through guesswork and supposition an entire world of possibility that simply cannot be known but we can’t help but wonder about.

These are like the maps made in the late 1400s, after Columbus returned to Europe and rocked the collective understanding of the world’s layout. In some maps, for example, Florida is in a strange place in relation to Honduras—right at its shores, actually–and up until about 1540 mapmakers imagined a place they called Arabia Felix. Griep’s images are like Arabia Felix. There is something immensely poignant about such human mistakes.

Hunting for What’s Out There

July 2, 2007

Jaime Kleiman

Jaime Kleiman interviews the Walker’s Philip Bither,curator of performance.

Do you see any fundamental differences in theatre that is made in North America versus theatre that’s being made in Europe? Are there similar themes, practices, or ideas threading through new work right now?

Regarding differences, it’s very difficult to generalize, and this is a subject worthy of long essay—or even a book—but here are a few thoughts: in Europe there is greater tolerance for conceptual (both in content and form) approaches and artists/producers feel less need to make performances “entertaining.” While this is mostly good—artists have a tremendous freedom to experiment, even on the largest scale, at times it results in work that feels insular or academic.

In the U.S. in recent years, ensemble and collective theater-making seems to be more dominant than in Europe, particularly in experimental and contemporary forms. Some of the ensembles that have emerged in the past decade in the U.S. represent a significant and exciting development. Our January Out There Festival has, in particular, become a home for the rising contemporary ensemble theater movement in the States. Groups like Elevator Repair Service, Big Art Group, SITI Company, Riot Group, Richard Maxwell’s New York City Players, Universes, Big Dance Theater, and many others offer tremendous promise for the future of theater. They are willing to shake things up in a way that most of the traditional producing theater company structures in America don’t allow.

A much more recent trend I’m noticing in the generation of theater/performance makers even younger than those mentioned above is what I might refer to “the new sincerity,” a rejection of an ironic, distanced, more post-modern stance that has tended to define the work of their predecessors. We will see several examples of this direction in several of the 20s- or 30s-something companies appearing in this year’s Out There Festival.

Warren MacKenzie, In His Own Words

July 2, 2007

Mason Riddle

Mason Riddle interviews Warren MacKenzie, mingei potter and ceramics legend.

Could you speak to the influences on your work?

The first influence was when Alix and I apprenticed at Bernard Leach’s pottery in St. Ives, England. Because we stayed in his house, we were around his collection of pots. We saw pots from China and Japan. It is also where we met Shoji Hamada, the master Japanese potter who worked in the mingei tradition. Through Leach and his book, The Potter’s Book, pottery became more available. Hamada, who was influenced by Korean folk pottery, took a tradition and gave it new life. I gravitated to his philosophy and how he threw pots. It was a philosophy of “don’t look at my work, but look at the influences of my work. These influences are stronger [than my pots] as they represent a culture.” Koreans didn’t have a word for “good or bad”, just mu, “it is.” Hamada’s work had tremendous breadth – it was an attitude – carried out as well as possible.

I like the historic pots of China and Japan and Korea, where the culture was more elemental, when these pots were beginning to be made. Much of contemporary Japanese pottery has become all too clever but fantastic in terms of technical skill. The potters have gained incredible skills, but they have lost an emotional reason to express. But, this is only my personal opinion.

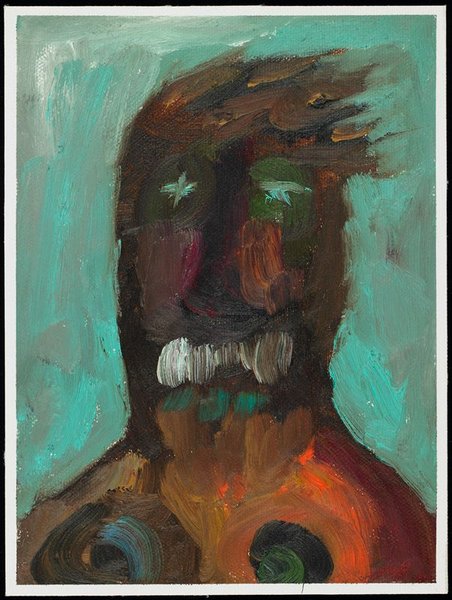

New Skins at MIA: Painting in a Whole New World

April 16, 2007

Ann Klefstad

Ann Klefstad reviews the work of Jim Denomie and Andrea Carlson at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

”New Skins” is big, in all ways. It’s an ambitious show that’s highly successful. Jim Denomie and Andrea Carlson both use their positions inside and outside the standard artworld to brilliant effect. The artists’ work is very different, but the pairing works. Carlson and Denomie are both of Anishinaabe ancestry, but more than that, they are fine artists with academic training and fully developed personal styles. They use their media in sophisticated ways, working out of both Euroamerican and native cultural traditions.

What was most instructive about this show to me was how rich the traditions of art are if they are approached not only from the inside, but with the perspective of someone who can both take a tradition and leave it—someone who can see it from inside and outside simultaneously. This eliminates stale strategies of quotation and irony, and opens up new potentials in the practice of painting. Both Carlson and Denomie are possessed of more than one tradition, and that seems to be a rich and liberating condition.